It's hard to believe that in the midst of midsummer I'm writing about winter stars and constellations. But there's a good reason.

If you have ever been outside on a winter's night you have no doubt enjoyed the sight of the year's brightest stars and constellations. But you also have likely cut short your observing session for a good reason: the cold temperatures. Many stargazers have been adversely affected by frosty, sometimes bone-chilling conditions. Such a pity, since there are so many glorious sights that the winter sky offers to us. How I've often wished that I could partake of the wonders of the winter sky from a warmer climate.

Indeed, it would be nice to gaze at the winter wonders from a spot in the Caribbean or south of the equator. But for those of us who simply cannot afford the time or money to get aware to such balmy localities in January or February, I offer a simple solution: This week, set your alarm clock for 4:30 a.m.

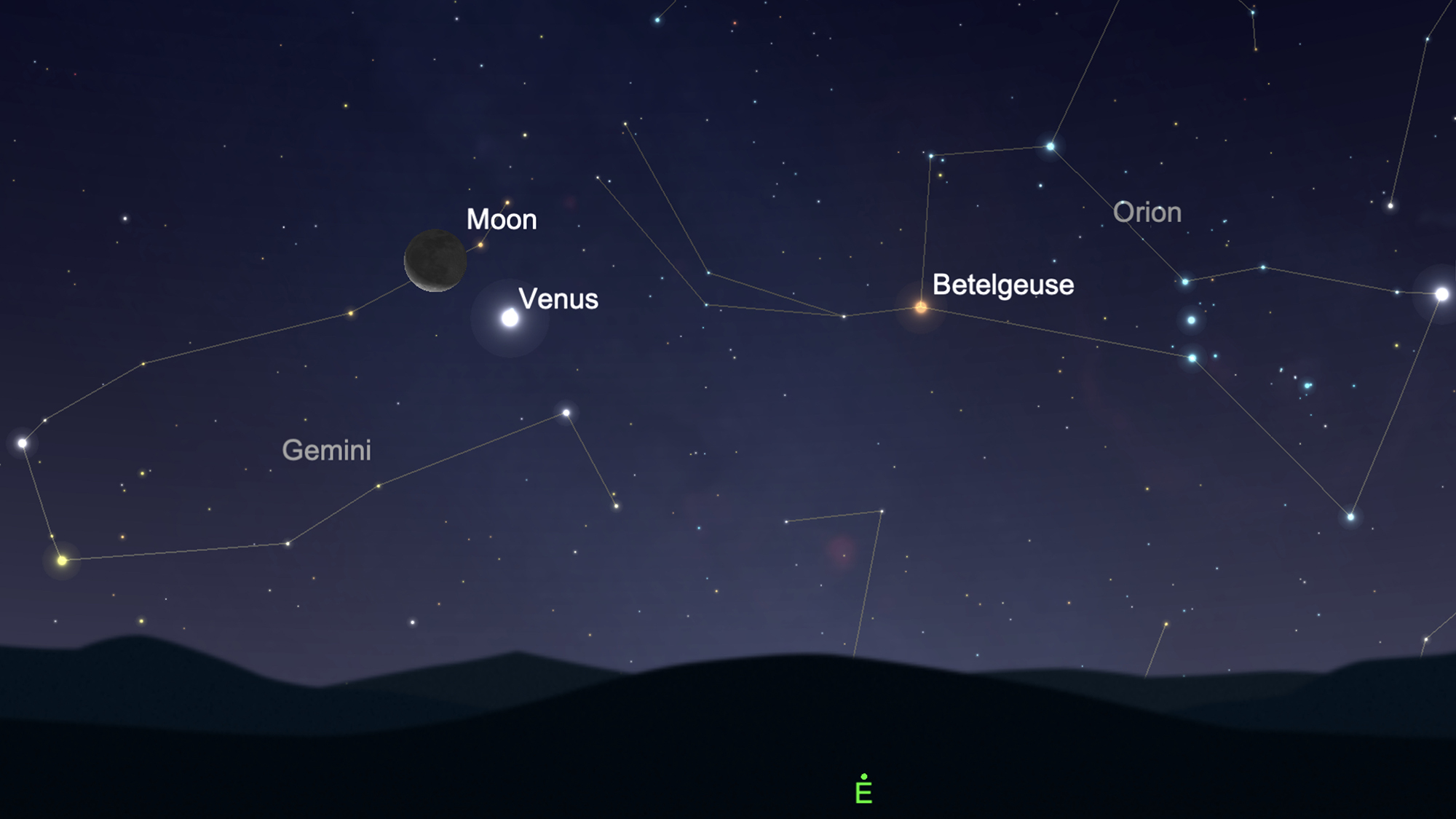

And here is something to entice you out of your bed; call it a bonus if you will. Early on Saturday morning (Aug. 15), The dazzling planet Venus will glow less than 4 degrees to the lower right of a slender crescent moon, an eye-catching celestial scene!

Related: Best night sky events of August 2020 (stargazing maps)

Venus will be in conjunction with the moon — meaning the two objects share the same celestial longitude while making a close approach — on Saturday at 9:01 a.m. EDT (1301 GMT), according to NASA.

For skywatchers in New York City, the sun will rise at 6:06 a.m. local time, so the pair may be difficult to see at the time of conjunction. However, early risers and night owls can still observe the close approach for a few hours before daylight. The moon rises over New York City at 2:06 a.m., followed by Venus at 2:33 a.m. local time.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Winter stars, sans the cold

If you step outside at a rather ungodly hour, you will be transported to the sky that will greet you on a typical early evening in January. Direct your attention low toward the west-northwest and you'll see the Summer Triangle getting ready to depart the scene; back when the night started it appeared almost directly overhead.

Soaring high above Polaris, the North Star are the five bright stars that form a zigzag row, somewhat resembling the letter "M" — the constellation of Cassiopeia, the Queen of Ethiopia. But when darkness had just started to fall about eight hours earlier, it had resembled a letter "W" hovering low over the northeast horizon.

But the real display can be seen over toward the southeast, where the sky is spangled with the bright luminaries of winter: the constellations of Orion, Taurus and Gemini; the bright stars Betelgeuse, Rigel and Capella; the beautiful Pleiades and Hyades star clusters as well as the Great Orion Nebula. They all bade us a fond adieu from our evening sky back in April as the last of the winter chill was fading and being replaced by milder springtime temperatures.

And now, they are all back in view to enjoy again — and this time, you probably won't need much more than a light jacket or sweater to fend off the early morning chill. Now you can break out your binoculars or telescope and enjoy these prominent star patterns without having to worry about possibly contracting frostbite or how low the wind chill factor will be.

Vying for your attention

Even to a casual observer, these bright stars and constellations are hard to miss. I remember as a very young boy spending the summers at my aunt and uncle's house on Long Island. In August, one day each year there was a big fishing trip planned on a boat which sailed out of the town of Babylon at the crack of dawn. My father took me along with him, where I would join other uncles and cousins on a day-long adventure out at sea.

But to me, the most memorable part of the trip was always at the beginning when we were loading the station wagon with our gear in the predawn darkness. I could not help noticing how dazzling and brilliant the stars appeared at that early hour. I didn't know much about the constellations back then, but there's no doubt in my mind that unknowingly I was probably admiring Orion and his retinue.

A signal that cooler days are on the way

Another object making its first appearance since it was last seen disappearing into the glare of the sun last spring is the brightest star of the night sky, Sirius. During July and early August, Sirius shines invisibly during the daytime. Legend had it that the light of the sun combined with the light of the brightest star of the night is what caused the extreme heat often experienced at that time of the year.

Since Sirius is the brightest star in the constellation of Canis Major, the big dog, and hence was known as the "Dog Star," the spell of oppressive summertime weather became known as the "dog days." The dog days officially come to an end on Aug. 11 with the "heliacal rising" of Sirius — its first appearance in the morning twilight sky, just prior to the rising of the sun.

So, regardless of how hot your local weather is or has been, this appearance of Sirius — a star we most associate with the winter season — now rising just ahead of the sun, is a subtle reminder that the hottest part of the year is now behind us and a promise that a change toward cooler weather is only a matter of some weeks away.

Four minutes make it all possible

The reason that we can see stars associated with the winter season in August is due to the Earth making one full rotation on its axis not in 24 hours, but rather four minutes shy of that: in 23 hours 56 minutes. As a result of this, the stars rise four minutes earlier every day than the previous day.

And those four minutes can quickly add up.

After 30 days, a star is rising two hours earlier. When this schedule is expanded to encompass an entire year, this adds up to 24 hours. So, this cycle repeats after one year. Five months from now — in mid-January — the night sky we now see at 4:30 a.m. will be in view at 5:30 p.m. (in places where daylight saving time is observed. Because we set our clocks back one hour in the fall, it's actually a difference of 11, not 10 hours).

Of course, by mid-January, average ambient nighttime air temperatures nationwide will be about 40 degrees Fahrenheit (22 degrees Celsius) colder than they are now, which is why it's so much more comfortable to enjoy the stars of winter ... in the summer!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.