1st map of moon water could help Artemis astronauts live at the lunar south pole

It's good news for the Artemis program.

The first map of the distribution of water on the moon could be used by future explorers traveling to Earth's natural satellite under the Artemis program.

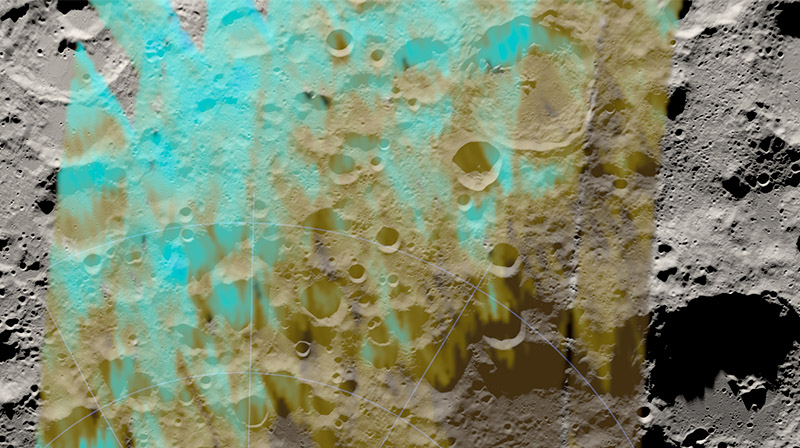

Astronomers have built the first map that shows how the supply of water on the moon changes with local geography, like the many mountains and craters that dominate the moon's airless, battered surface. The map, which covers one-quarter of the moon's Earth-facing side, was put together with data gathered by NASA's Stratospheric Observatory For Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) telescope during its final year of observations before being grounded. (The retired SOFIA is now on display in a museum in Arizona.)

The study's findings are based on SOFIA's capability of detecting water at a wavelength of six microns, which is "uniquely sensitive to the water molecule," Paul Lucey, an astronomer at the University of Hawaii and the study's co-author, said Wednesday (March 15) at the 54th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC) being held in Texas and virtually.

Related: Moon facts: Fun information about the Earth's moon

Previous missions like India's Chandrayaan-1 have hunted for water's chemical signature or fingerprint on the moon, came close to finding it but ultimately did not succeed. Water's chemical fingerprint is very close to its relative called hydroxyl, which has one less hydrogen atom. So most previous missions that watched the moon at wavelengths of three microns — different from SOFIA's more-sensitive infrared observations at six microns — were not able to distinguish between confusingly similar molecules of water and hydroxyl. In 2020, SOFIA became the first mission to unambiguously detect water at the moon's south pole; researchers then calculated there to be about 12 ounces of water per one cubic meter of lunar soil.

"SOFIA provided the only opportunity to observe the moon at a wavelength of 6 microns," Casey Honniball, a researcher at University of Maryland and co-author of the study, said during her presentation at LPSC. "Fortunately, water has a unique fingerprint at 6 microns that cannot be confused with hydroxyl."

So Honniball's team revisited SOFIA's data collected in February 2022. This time around, instead of trying to find how much water is present, the team studied how its presence changes across the lunar surface. Across a large chunk of the southern hemisphere, the data showed a lot more of water's unique chemical signals on the inner sides of lunar geographical features shaded from sunlight than on ones exposed to the sun.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We do confirm the presence of water and not just hydroxyl in a wide-spread distribution across a large part of the southern hemisphere," co-author William Reach said during his presentation at LPSC.

One of the features in the area is the famous impact crater Moretus — a 71-mile-wide (114 km) dent almost as large as Hawaii's Big Island with a central peak stretching for 1.3 miles (2.1 km). Researchers found that the peak's "anomalously cold" southern side holds onto more water in the form of ice while its northern side, which receives sunlight for a long time each lunar day, runs at a deficit. This is similar to how "skiers on Earth know the slopes receiving less direct sun retain snow longer," according to a statement by the Universities Space Research Association (USRA).

During their presentation, the study's researchers said that they could not use any ground-based telescopes because the water in Earth's atmosphere blocks all the signal coming from water on the moon. "SOFIA, however, flew 99.9% above Earth's atmospheric water, allowing us to detect lunar water," Honniball said.

An open question from these developments is where all the water is coming from. Scientists have a few theories: Asteroid impacts, evaporation from Earth's atmosphere, delivery by solar wind, and sometimes from the minerals on the moon itself.

"Our common knowledge from the Apollo era that the moon is bone dry was wrong," Lucey said in a statement. "We already know it's wrong, but the question is by how much."

They hope that upcoming missions to the moon that explore its south pole may find a more definitive answer. For example, NASA's VIPER (or Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover), scheduled to launch in 2024, will map water-ice and help scientists find out if this water is sprouting from deep within the moon, or if it is simply shallow and near the surface.

VIPER is also exciting because it is a part of NASA's Artemis program and is expected to provide astronauts with the knowledge they need to harvest lunar ice into water safe enough to drink and maybe even useful enough to fuel landers and rockets in the future.

The research is described in a paper published Wednesday (March 15) in The Planetary Science Journal.

Follow Sharmila Kuthunur on Twitter @Sharmilakg. Follow us @Spacedotcom, or on Facebook and Instagram.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston.