There's lots of water on the moon for astronauts. But is it safe to drink?

Two space agencies say we need filter systems for drinking moon water, and they need the public's help with the AquaLunar challenge.

Water appears to be abundant near the moon's south pole, but drinking it could be a safety problem for astronauts.

A new moon challenge asks the public for ideas to purify drinking water for astronauts, reducing the need for shipments from Earth. The Aqualunar contest is open to residents of Canada and the United Kingdom, and you can send in your ideas right now, through April 8.

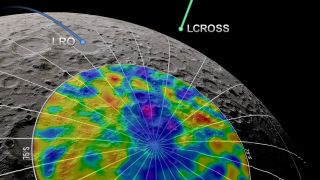

"It is very likely that water exists on the moon, but it contains contaminants," the Canadian Space Agency wrote in its briefing for participants. That statement is based on data from a deliberate crash of a NASA spacecraft, LCROSS, into the icy south polar region of the moon on Oct. 9, 2009.

Related: How NASA's bold moon crash almost bombed

The resulting plume from LCROSS (short for "Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite") not only contained the hydrogen expected from water, but also featured carbon monoxide, calcium, mercury and magnesium, according to a 2010 Science paper about the discovery led by researcher at NASA's Ames Research Center in California.

Magnesium and calcium are commonly found in "hard water," but mercury is a highly toxic substance. As such, contaminants like it cannot be consumed by astronauts with the NASA-led Artemis program, who are expected to touch down at the south pole later in the 2020s.

"Lunar purification of in-situ water has never been demonstrated successfully on the lunar surface, and there are multiple challenges that exist in a space-based environment," CSA officials stated in the Canadian guidelines. While space solutions commonly help remote communities on Earth (a priority of CSA's mandate), the technology that exists today is not as beneficial, the agency noted.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Issues the challenge participants will face in their designs include the highly corrosive lunar soil (or regolith), the need to ship low-mass systems to the moon due to rocket lifting constraints, and the requirement to operate in only one-sixth of Earth's gravity on the moon's surface, among other problems, the CSA added.

The U.K. Space Agency's guidelines for participants additionally outline a number of contaminants participants will need to account for, including hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, carbon monoxide, ethylene, sulfur dioxide, methanol and methane, along with "traces of solid regolith."

The solutions are expected to benefit numerous audiences, the U.K. Space Agency wrote in a press release, including "removing microplastics from the oceans [and] providing clean drinking water in low-income countries and drought-prone areas."

Each country has its own judging process, funding and eligibility, and more details for participants in each country are available at the respective websites linked above. Generally speaking, participants will be expected to submit a concept design by April 8. If selected for further stages, teams will next submit proofs of concept and prototypes in new rounds, with the grand prize in each country announced in 2026.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace