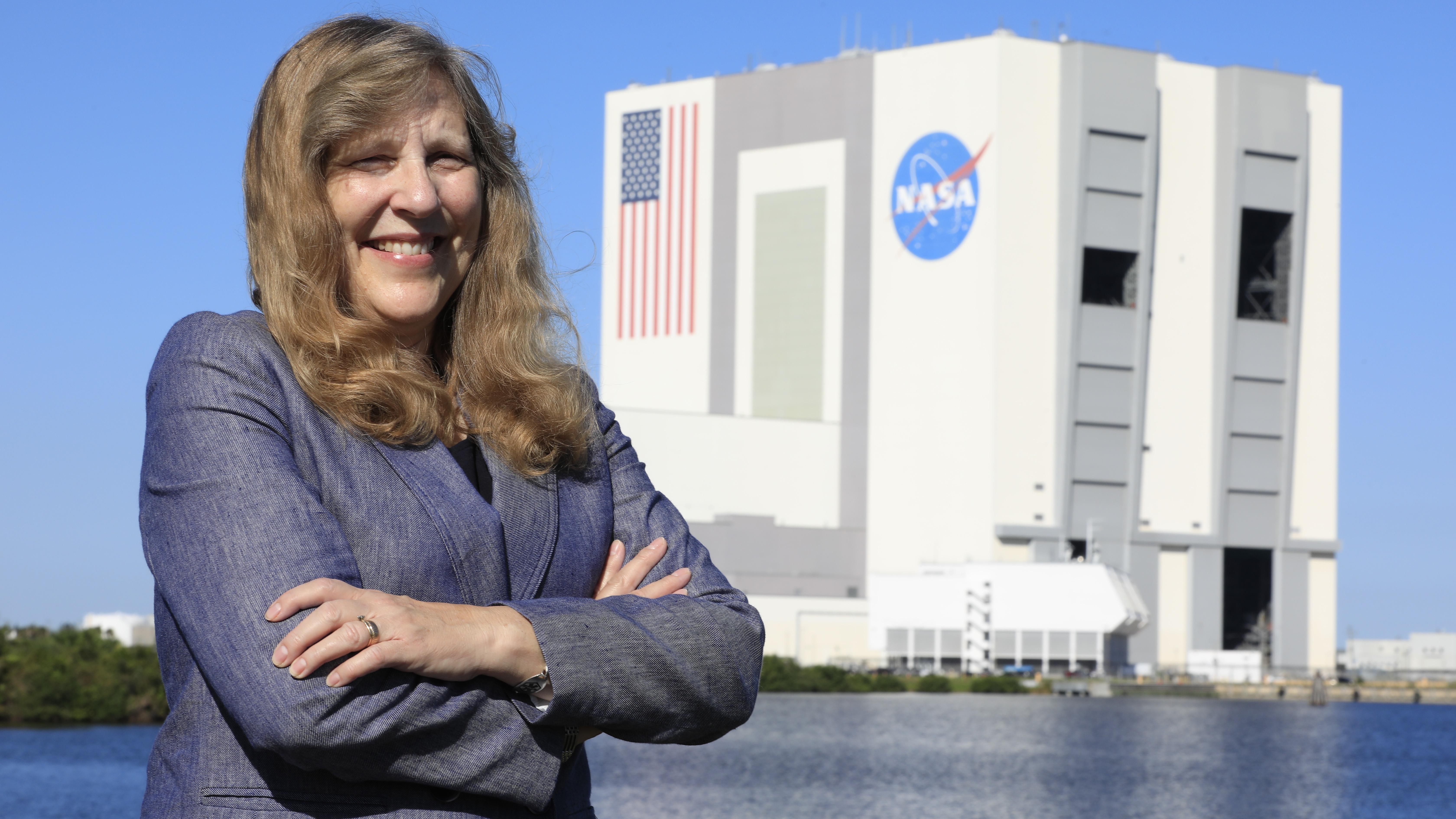

NASA's 1st female chief engineer at Kennedy Space Center wants to put a space station around the moon (exclusive)

"If everybody thinks alike, you're not thinking about the problem correctly."

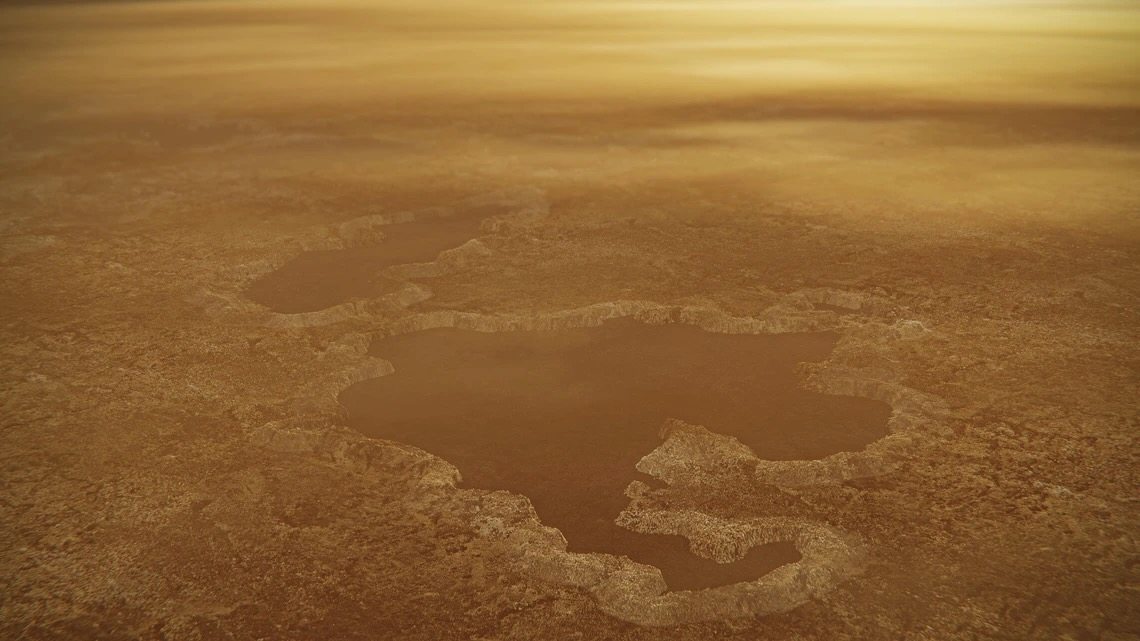

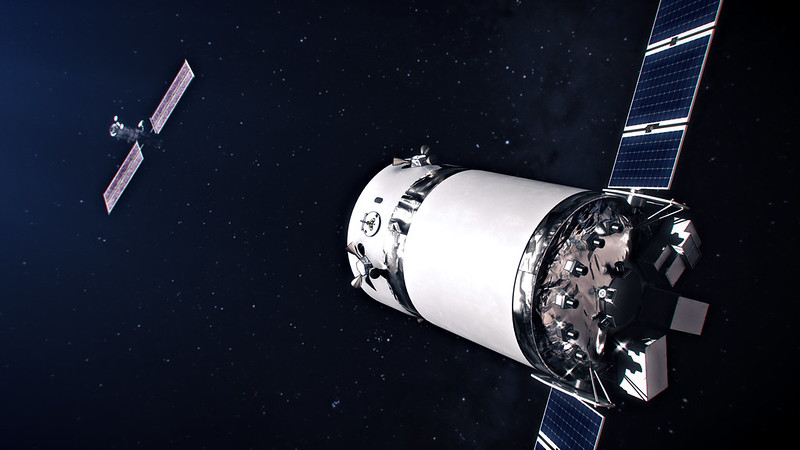

When NASA builds its first space station near the moon, how will we ship items out there?

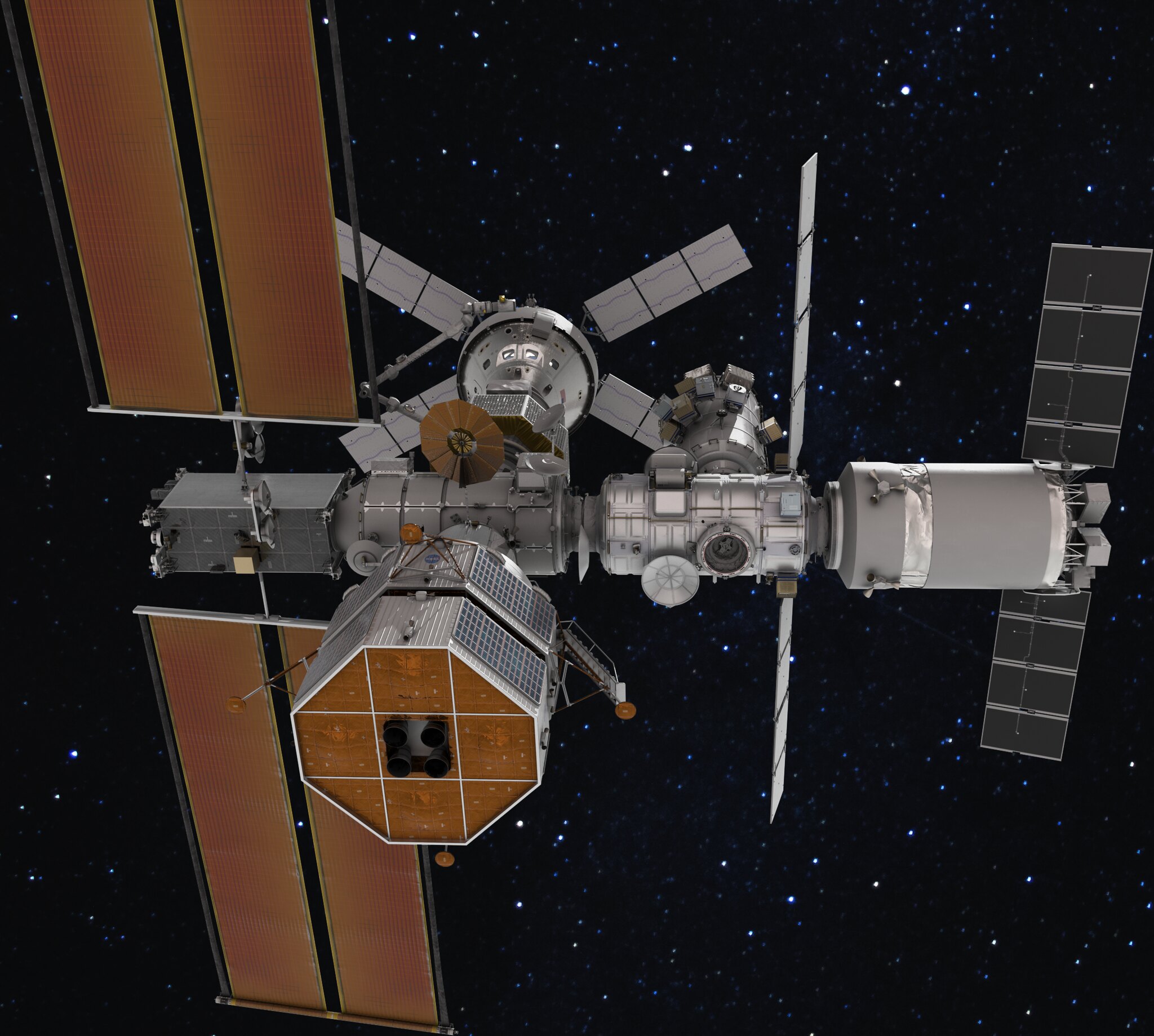

Teresa Kinney, NASA's first female chief engineer at the agency's Kennedy Space Center (KSC), is one of the managers working to put the Gateway lunar space station together in orbit around the moon later in the 2020s. Gateway will support Artemis program landing missions on the moon in the next decade or so, but like the International Space Station, it needs to be built first.

Kinney also works in Deep Space Logistics, which is the Gateway project office at KSC that is working to get all the commercial cargo services lined up to ship things for astronaut crews: Cargo, equipment and consumables. She sat down with Space.com during Women's History Month to talk about her journey to her current role, and how she's mentoring younger team members.

Related: NASA's Dana Weigel will be the 1st female ISS program manager

Space.com: Before we jump into talking about your career, can we talk a bit about the fact that we have four women on the International Space Station right now? And just how exciting that is to meet that milestone for a third time.

Kinney: It's very exciting for all of us, anytime there's a first and anytime you can see you've done something that's a little bit different. The fact that it's during Women's History Month makes it even more special. I knew a couple of astronauts pretty well, and they are all rock stars. You just are impressed by everything they do, and so I'm very excited for them. They must be having a great time.

Space.com: Where did your interest in space first begin?

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Kinney: When I was a kid, my dad was in the military. We lived in Germany, and he woke us all up and got us around the TV to watch Apollo 11. When we had Apollo-Soyuz, he dragged us all down to KSC to see the hardware afterward. So you know, lifelong interest in it. When I started college, I looked at a lot of things and I thought, "I really love space, and why not try?" So I got a co-op job and just kept following all the challenges. I moved around a lot, based on what was hard. I've learned a lot, when it's hard. So it's exciting for me, and I feel a little bit smarter, and I get a little more experience. So it's all good.

Space.com: What kinds of other educational experience did you have, like degrees and certifications?

Kinney: I co-oped just under five years. I have a bachelor of science in mechanical engineering. I have a master of science, industrial engineering for systems engineering. I have certifications in welding, machining, forklift operating, crane operator, all the things you would need to do large tests. Those things really enabled me to understand and help with large testing programs. I've been a part of quite a few of those. I also did a Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) certification in turbomachinery regional jet engines. Just looking at things from different perspectives. But space was my love. So I came back to space.

Space.com: What does that hardware experience bring into your role?

Kinney: It really, actually, helps a lot. When you're doing analysis, understanding the hardware is phenomenal, which is why KSC is such a great fit for me. Because if you want to look for hardware, this is the center. But a lot of the big tests — you know, my career has been primarily in structural dynamics, acoustic vibrations, some large structure things — you have to do all your flight simulations via computer. But you want to anchor your models (in real-life experience).

Related: Space history and future leap off the screen at NASA's Kennedy Space Center

Space.com: Can you step me through the pathway that got you to your current role?

Kinney: I started out working Spacelab (on the space shuttle program). Spacelab was an amazing experience where you had 144 experiments. So all of those, you're doing certification on hundreds of things for every mission. And I did that for quite a long time, over a decade, and really enjoyed it.

Then they started space station. How do we do payloads on space station? I thought, that sounds challenging. So I worked space station for several years, and worked on the racks and the modules. And then I got asked if I could help with the first certification for analysis of FAA, so I did that for a few years.

Then I came back to do return to flight [after the Columbia disaster of 2003, caused in part by a piece of debris hitting the spacecraft]. That was impact debris analysis. Then I got this great opportunity to come down to LSP [NASA's Launch Services Program]. They were looking for structural dynamicists and structural engineers. That is where I got to come to KSC, and I found out I fit in here great.

I got pulled into the Ares 1-X (prototype launch system), and some of the shuttle stuff, supporting the chief engineer. I also worked commercial crew on Boeing Starliner. For over a decade, I was the integrated performance lead engineer, which is basically the same as flight analysis, reporting directly to the chief engineer for the program. So I did that for about a decade, when I had this great opportunity to come to Deep Space Logistics, which is going to go fly to the Gateway, like ISS. Then I got to be the chief engineer last October.

Space.com: For that Deep Space Logistics role, can you tell me in a bit more detail what you were doing?

Kinney: For Gateway, when I first started, we started going through how do you define requirements for transit? How do you do testing? How do you accept alternate approaches to doing things? Because if you do it the NASA way, international partners don't know how to do it the NASA way. They have their own ways, and different companies have their own ways. How do you do that education to compare things and say, yeah, there's more than one way to get there.

Space.com: What do you do as chief engineer, day to day?

Kinney: A chief engineer is basically the tech authority, or making sure that you have the right reliability, the right mission success, of all of the things — evaluating risks to the roll-up of all the different subject matters. Instead of being the expert in guidance and control, or loads and dynamics, or structures, you're looking at how the entire system operates, and you're getting input from everyone.

I work very closely with the tech authority for safety and mission assurance. We're going to the same place, which is we want to be successful. We want the team to be successful. We want Gateway to be successful. We're responsible for all of the things that are related to the technical functionality and structural capability of the Gateway Deep Space Logistics.

Under my job as the chief engineer, I do only Gateway Deep Space Logistics as a tech authority. I report directly to the project, and to the program chief engineer for Gateway. So I have those two paths that I coordinate with.

In my other hats, I'm a deputy tech fellow for loads and dynamics, since I've done that for over 30 years. So in that role, I get to do things like Space Launch System (SLS) integrated modal test, I get to do SLS rollout. Those kinds of other peer reviews are very intricate, like standing review board type evaluations on programs that are not mine.

Space.com: There were a few rollouts of the SLS for Artemis 1, back and forth, before launch in 2022. So what did you learn that is helping you prepare for Artemis 2's launch in 2025?

Kinney: During the rollout, we look at the instrumentation under some significant input loads, because it's rolling down the crawler way. You get some big vibrations. You can look at how the vehicle behaves under wind and under that excitation from the crawler on the gravel, and look at your how your model is behaving. Then you can say, "Hey, my model is behaving under these kinds of forcing functions." It gives you more confidence that the model you're using for all of your flight analysis is good in these different regimes.

There were some changes to the mobile launcher, right, after launch. They had some things they wanted to beef up and repair. As you look at instrumentation, you know, all the different groups are saying, "Maybe I want to move this," or "Maybe I want to know more about this." So there's there's more data, different data.

Related: NASA's Apollo-era crawler, upgraded for Artemis, sets Guinness world record

Space.com: As a manager, what are you trying to do to help your teams? What kind of a manager, in other words, are you trying to be for them?

Kinney: I'm trying to be a leading and collaborative manager, because I want them to be successful. A lot of our team has not done this kind of launch, and this kind of flight to unmanned system. I'm making sure we leverage the expertise that we can pull in on what's happening on other programs.

We have a process where we put in a technical issue to evaluate. So I'll pull it together into a review board, or at least into a review item, that we would all have that discourse on how did these different things influence it? How do you decide what the path forward is?

Space.com: How do you try and foster that kind of environment of diversity? And when you do so, what do you see as the benefits for your team?

Kinney: The whole project fosters this. It makes it very easy for me. But I try to identify people's strengths and pull them in from those strengths. Because one thing I learned from one of my mentors, who was a chief engineer, is that if everybody thinks alike, you're not thinking about the problem correctly.

Space.com: What's your big focus in the coming years?

Kinney: My big focus is to get our first Deep Space Logistics modules [into space] and to support Gateway. One of the reasons I think I'm maybe very good at this job is because I've seen a lot of this before on the ISS, where everything's trying to gel and they're trying to time ... all those pieces to come together. Because I've seen this before, we can kind of help and say, 'Okay, here's what's coming. Here's some of the troubles they had. Let's help make Gateway be successful.' Because you don't want them to stumble over something that somebody else has stumbled on in the past.

Space.com: Anything else you'd like to share?

Kinney: One takeaway I have is the value of being the face of somebody that's done something a little bit different. I got to see it firsthand at a conference, where I was sitting with my friend, [NASA astronaut and engineer] Stephanie Wilson. There were young girls that came up at the conference, young 20s. They were saying things like, 'I am an engineer because of you. You are my role model.' I said, 'That's because they can see the opportunity, because she's ahead of them, and because she's visible and does a lot of outreach.'

Stephanie and I do a lot of outreach, but I never really saw that feedback loop. I thought, we really have to be those people that are out there going, 'Anybody can do this. It is an option for you. You have to start looking at it. Here's the same kind of person as you, maybe the same background, the same whatever. They're successful.'

At KSC, a whole lot of people are coming very close to retirement within the next decade or so. This is the time to get people in: 'Hey, STEM (science, engineering, technology and math) is good. Come join us.' I am hoping to get some of those folks (interested in) working space, because this is a better time than I've ever seen in the agency in my 40-something years. This is the best time I've seen for opportunity.

That's one of the reasons, when NASA said, "Do you want to do interviews about this?" I'm like, "Yeah, because I want people to think I could do that too."

This interview has been edited and condensed. The original version also misstated Kinney's name as "Kinsey" in multiple places; that error has been corrected.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

-

Fission Reply

Well, if a lunar space station is necessary to support the Artemis program, that will push up the cost probably by hundreds of billions of dollars. As the true cost of this program accelerates, we need to ask up front what the goals of the program are and an outside audit of the projected expenses before proceeding along this path that will bankrupt just about all other scientific exploration. What are the advantages this manned program can offer over non-manned space exploration at this time? All I have heard about are the plan to establish a colony on Mars. And for what purpose? Especially when, at present, it appears that the last several attempts at a lunar landing by other nations resulted in the spaceship falling onto its side. At present there is too much about the Moon that is unknown to even contemplate such science fiction type projects.Admin said:For Women's History Month, NASA's Teresa Kinney shared what she's learned in 40 years of working in agency circles, and how she's trying to help the next generation fly to space.

NASA's 1st female chief engineer at Kennedy Space Center wants to put a space station around the moon (exclusive) : Read more -

Fission Even worse, assuming we establish a colony on Mars. The movie "The Martian" is probably a realistic portrayal of what the colony might be unprepared for and what might happen. Many have suggested that establishing a colony would be a suicidal mission. with no chance of rescue. Hollywood can provide a safe ending. It is doubtful that NASA would be able to do anything in similar circumstances. With no chance of rescue many have suggested that establishing a colony would be a suicidal mission. Just because humans volunteer for such a mission does not make it right to send people to Mars.Reply

As we say in the medical field, "First do no harm!" -

Giin Reply

The realism in that movie started after he was left behind, the events prior had no basis in reality and would never happen. The maximum force of the wind of a bad Martian sandstorm is best compared to the force of a toddlers sneeze as felt from 10 feet away. That's NASA's comparison, by the way. A Martian sandstorm could never risk blowing over a launch vehicle and necessitate an emergency evacuation.Fission said:Even worse, assuming we establish a colony on Mars. The movie "The Martian" is probably a realistic portrayal of what the colony might be unprepared for and what might happen. Many have suggested that establishing a colony would be a suicidal mission. with no chance of rescue. Hollywood can provide a safe ending. It is doubtful that NASA would be able to do anything in similar circumstances. With no chance of rescue many have suggested that establishing a colony would be a suicidal mission. Just because humans volunteer for such a mission does not make it right to send people to Mars.

As we say in the medical field, "First do no harm!" -

hectormayhem There's something so condescending about putting the spotlight on the chief engineers sex instead of her qualifications and accomplishments, but also pointing it out that you did the interview for "women's history month" is just insulting.Reply -

MrWhite Reply

Totally agree. Focusing so much on sex makes it seem like there were other male candidates that were passed over just to make some headlines.hectormayhem said:There's something so condescending about putting the spotlight on the chief engineers sex instead of her qualifications and accomplishments, but also pointing it out that you did the interview for "women's history month" is just insulting. -

It'smeagain Why don't we try putting a space station around the Earth first. That seems like the logical first step to me.Reply