NASA will launch its 1st asteroid-defense mission this month

Brace for impact, Dimorphos.

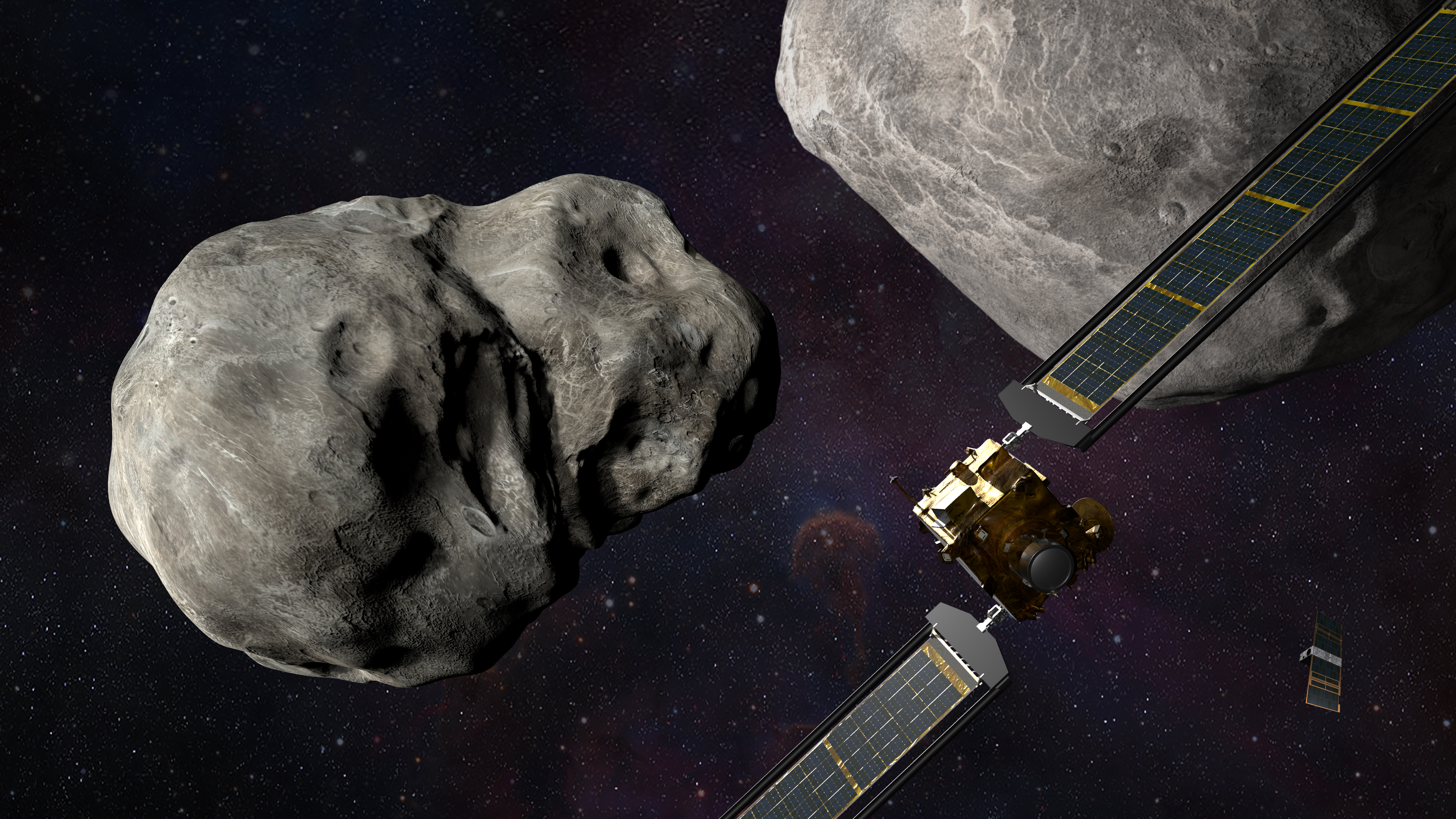

NASA has lofted countless spacecraft into the solar system, but a mission launching in late November will attempt a unique feat: to slam into a tiny asteroid and slightly speed up its orbit.

The mission, known as the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), is NASA's first foray into active planetary defense. Planetary defense seeks to detect large asteroids that could potentially collide with Earth, evaluate the risk these rocks pose and, if need be, attempt to avert calamity. DART will test one technique for that last step by slamming into the smaller moon of an asteroid while humans watch closely to see how much the moon's orbital period shortens.

"If there was an asteroid that was a threat to the Earth, you'd want to do this technique many years in advance, decades in advance," Nancy Chabot, a planetary scientist and the DART coordination lead at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland, said during a prelaunch news conference held on Thursday (Nov. 4). "You would just give this asteroid a small nudge, which would add up to a big change in its future position, and then the asteroid and the Earth wouldn't be on the collision course."

Related: Humanity will slam a spacecraft into an asteroid to help save us all

To understand why scientists are worried about asteroids, consider the fate of the dinosaurs. It's just the sort of impact that wiped out most such creatures about 66 million years ago that specialists in planetary defense are trying to avoid.

Planetary defense comes in two phases. The first requires searching the skies for as many space rocks as possible, then tracking asteroids closely enough that scientists can model trajectories and compare them to Earth's orbit long into the future. To date, NASA tallies show that scientists have identified more than 27,000 near-Earth asteroids, of which nearly 10,000 are larger than 460 feet (140 meters) across, the size at which experts worry that space rocks could cause major regional damage.

Right now, planetary defense experts know of no sizable asteroids on track to hit Earth. But should they identify one, the second phase of planetary defense kicks in: attempting to do something that prevents humans from going the way of the dinosaurs.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Would-be planetary defenders have evaluated a few different techniques for moving an asteroid off a collision course with Earth, and DART is designed to test the one referred to as a kinetic impactor. (That's just a fancy name for slamming a large enough mass at a high enough speed to nudge an asteroid out of a dangerous trajectory.)

DART, a $330 million mission, will launch aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California. The launch window opens on Wednesday (Nov. 24) at 1:20 a.m. EST (0620 GMT; Tuesday, Nov. 23, at 10:20 p.m. local time); launch opportunities continue through February 2022.

By next fall, DART will arrive at a near-Earth asteroid system consisting of Didymos, which is 2,500 feet (780 m) across, and a much smaller moonlet. That moonlet, formally dubbed Dimorphos, is just 525 feet (160 m) wide, a little larger than the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt.

And Dimorphos is DART's real target — more literally than is usually the case for spacecraft. DART will fling itself head-on into Dimorphos. The maneuver, scientists have calculated, should speed up the moonlet's nearly 12-hour orbit by at least 73 seconds, and perhaps by more like 10 minutes.

A cubesat flying with DART will monitor the spacecraft's fatal collision for mission personnel on Earth; ground-based telescopes will also help observe the impact and how it affects Dimorphos' orbit around Didymos. And, a few years from now, the European Space Agency plans to launch a probe called Hera to assess the collision's aftermath up close.

The mission team hopes that DART will give scientists their first real data about how a kinetic impactor approach to planetary defense might work in the real world, not just in models.

"Asteroids are complicated: they look different, they've got boulders, they've got rocky parts, they've got smooth parts, they've got weird shapes — all sorts of things are going on there," Chabot said. "Doing this real-world test on a real asteroid is why we need to do DART."

Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct the size comparison for Dimorphos. Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.