The Centaurs may get their first-ever close-up soon.

These space rocks — so named because they're hybrids of a sort, displaying characteristics of both asteroids and comets — have long intrigued astronomers. Part of the interest boils down to simple curiosity: Little is known about Centaurs, because no spacecraft has ever visited one.

But that may not be true for much longer. NASA is evaluating two proposed Centaur missions for potential launch in the mid-2020s via the agency's Discovery Program, which develops low-cost robotic exploration missions. ("Low cost" is relative, of course. Discovery missions are capped at $500 million, excluding the launch vehicle and cost of mission operations.)

Related: Our Solar System: A Photo Tour of the Planets

"The Centaurs are rising," said Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado. "The fact that there are competing Centaur missions is, in my mind, a sea change."

Stern, the principal investigator of NASA's New Horizons mission, leads Centaurus, one of the new Discovery candidates. The other Centaur concept, Chimera, is headed by Walt Harris of the University of Arizona's Lunar and Planetary Laboratory.

"Emissaries from the Kuiper Belt"

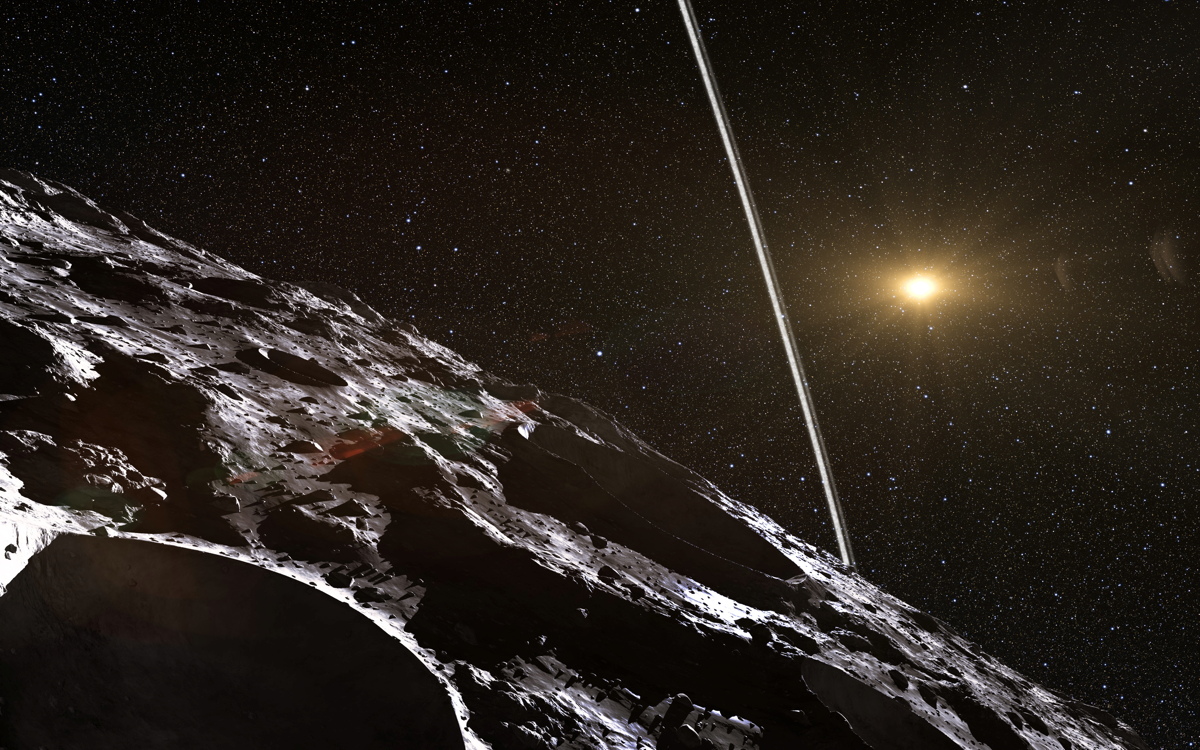

Centaurs dwell in the giant-planet realm, the neighborhood of Jupiter and Saturn, and were likely born there as well. But they've spent the vast majority of their lives in the Kuiper Belt, the ring of frigid bodies beyond Neptune's orbit.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Scientists think that one set of gravitational nudges sent Centaurs way out there long ago and another set returned them closer to the sun much more recently — just in the past few million years or so. Centaur orbits are dynamically unstable, so these bodies can't have been in their current positions for very long. Indeed, "Centaur" is probably a short-lived transitional state between Kuiper Belt object (KBO) and Jupiter family comet (JFC) in most cases, astronomers say.

"We can think of Centaurs as emissaries from the Kuiper Belt," Stern told Space.com. Centaur missions are therefore shortcuts to that region, he added: "They are ways to explore the Kuiper Belt at much closer range."

And exploring the Kuiper Belt is a priority for researchers trying to piece together how the solar system formed and evolved. Objects in those dark and frigid depths have been altered little by solar heating and therefore preserve primitive material from very long ago.

"They're wonderful time capsules," Stern said.

We've already gotten our first good looks at KBOs, thanks to New Horizons. The spacecraft flew by the region's most famous resident, the dwarf planet Pluto, in July 2015 and zoomed past the much smaller 2014 MU69 (known informally as Ultima Thule) on Jan. 1 of this year during an extended mission.

These two flybys, the only KBO encounters to date, opened scientists' eyes to the diversity and complexity of this far-flung realm. For example, New Horizons discovered towering water-ice mountains and vast plains of nitrogen ice on the 1,475-mile-wide (2,375 kilometers) Pluto. And the probe found the 20-mile-wide (32 km) Ultima Thule to be composed of two lobes, one of which is weirdly pancake-shaped.

Related: Destination Pluto: NASA's New Horizons Mission in Pictures

A centaur survey

Centaurus would build on the survey work that New Horizons has begun. (The latter probe may not be done in this regard, by the way; New Horizons has enough fuel to fly by another KBO if NASA approves an additional mission extension, Stern has said.)

Centaurus would cruise past the roughly 30-mile-wide (50 km) Schwassmann-Wachmann-1 (SW1) and the 140-mile-wide (225 km) Chiron, and fly by additional Centaurs as well. (The team isn't ready to share the planned number of encounters at this point, Stern said.)

The solar-powered mission would therefore provide looks at KBOs of previously unexplored size classes — those bigger than Ultima Thule but smaller than Pluto. And SW1 and Chiron are both fascinating in their own right, Stern said.

For example, SW1 is incredibly active, exhibiting powerful comet-like outbursts about seven times per year on average. It's unclear what exactly is driving these outbursts; they occur far too frequently to be caused by the heating associated with close solar approaches. (SW1 takes more than 14 Earth years to complete one lap around the sun.)

"Chiron's attributes are even more impressive; it is the second-largest Centaur, ~2,000x as voluminous (and presumably about as much more massive) as MU69, and [it] also frequently shows a coma," Centaurus deputy principal investigator Kelsi Singer, also of SwRI, Stern and their team wrote in a poster they presented in Geneva this month at EPSC-DPS 2019, a joint meeting of the European Planetary Science Congress and the American Astronomical Society's Division for Planetary Sciences.

"Further, stellar occultations have shown that Chiron also hosts dense orbiting rings or dust structures," the team added. "No mission has explored these puzzling phenomena around any body."

NASA has earmarked two launch windows for the Discovery candidates under consideration in this round: 2025-2026 or 2028-2029. Centaurus could launch during either window, Stern said. The mission's first flyby would take place in the early to mid-2030s, and Centaur encounters would continue into the 2040s.

"We'll do flyby after flyby," Stern said. "This mission is the gift that keeps on giving."

Time is of the essence for the Centaurus mission concept, he added. The team aims to fly by Chiron when the Centaur is at perihelion, its closest approach to the sun. Pulling this off, and also getting to SW1 (and other Centaurs as well), requires a launch in the 2026 to 2029 timeframe — or a nearly half-century wait for the next friendly orbital-dynamics window, Stern said.

Focusing on SW1

Chimera would take a different approach, focusing solely on SW1. The solar-powered probe would launch in the 2025-2026 window, get to SW1 in 2038 and study the curious object from orbit for a minimum of two years.

Chimera would therefore witness multiple outbursts up close. The data haul would be unprecedented, Harris said. Astronomers have never had a ringside seat for a large-scale cometary outburst before, and they don't really know what drives such dramatic activity.

As far as getting such information goes, an orbital mission to SW1 is "the only opportunity to do it in the solar system that we know of," Harris told Space.com, citing the Centaur's regular activity.

And, as with Centaurus, launching Chimera in the upcoming window is imperative, he added.

"The orbital trajectory we found for this object is a once- or twice-per-century opportunity," Harris said. "If we don't make it this time, it's going to be another 50 years before we can go back with this kind of mission."

Moreover, there's no guarantee that SW1 will still be as active 50 years from now. The object was nudged into its current, nearly circular orbit by Jupiter in 1974, Harris said, and SW1 will have another encounter with the gas giant around the time Chimera is slated to arrive. Therefore, the Centaur might soon be pushed onto a more elliptical path that features fewer or less-dramatic outbursts.

Over the longer haul, by the way, SW1 will likely become a Jupiter family comet, its orbit shifting to take it through Earth's neighborhood during the object's closest passes to the sun. This will probably happen in the next few thousand years, Harris said.

SW1 likely hasn't been through the inner solar system yet, he added. It's a safe bet that it hasn't done so during recorded human history, anyway; the arrival of such a big, bright comet every half-dozen years or so would certainly have merited some mention in the historical record.

SW1 as a JFC that occasionally makes very close approaches to Earth "would be the most spectacular comet ever seen," Harris said. "I figure there would be religions based on it."

Related: Photos: Spectacular Comet Views from Earth and Space

How to choose?

Both Stern and Harris stressed that momentum is building for a Centaur mission, citing New Horizons' pioneering work as a key driver.

But such interest predates that probe's epic encounters. After all, the 2003 Planetary Science Decadal Survey flagged Centaurs as promising exploration targets, a distinction repeated in the 2013 edition. (The U.S. National Research Council publishes a Planetary Science Decadal Survey every 10 years to help shape NASA's exploration priorities.)

Stern and Harris also lauded each other's mission concepts, with each researcher saying that both Centaurus and Chimera would contribute valuable information about the formation and evolution of our solar system.

And NASA may not have to choose between the two concepts; the agency is expected to pick two missions during the current Discovery round, one for each launch window.

"I think they should do both," Harris said.

We'll know more relatively soon. Finalists for the launch slots will be announced in January 2020, NASA officials have said.

- Best Close Encounters of the Comet Kind

- Solar System Facts: A Guide to Things Orbiting Our Sun

- New Horizons' Ultima Thule Flyby in Pictures

Editor's note: The original version of this story incorrectly stated that the cost cap for the next round of Discovery missions is $450 million. It is actually $500 million.

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.