NASA crashes DART spacecraft into asteroid in world's 1st planetary defense test

The DART spacecraft is no more.

This story was updated at 9:09 p.m. EDT.

LAUREL, Md. — For the first time in history, a spacecraft from Earth has crashed into an asteroid to test a way to save our planet from extinction.

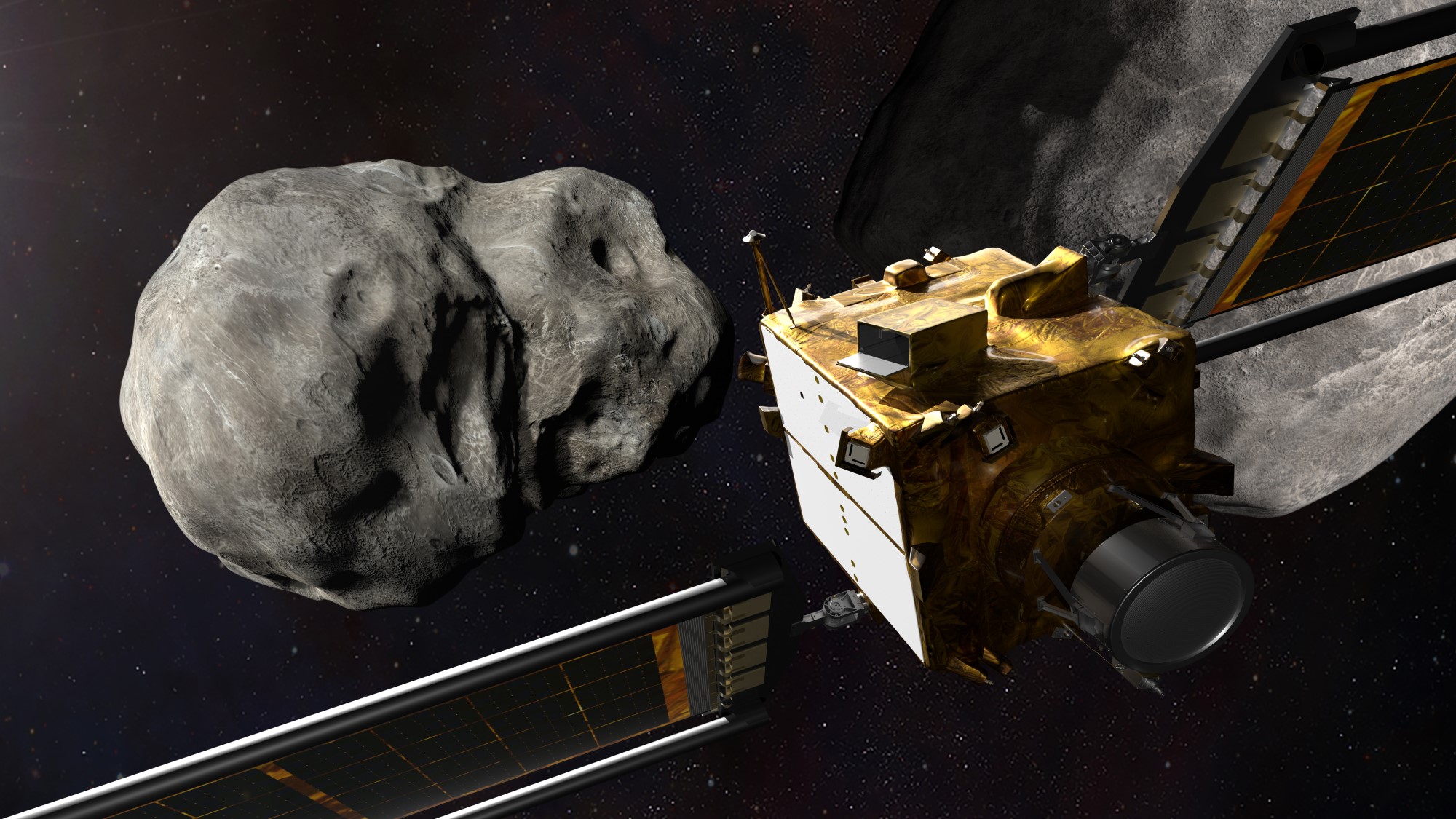

The spacecraft, NASA's Double Asteroid Rendezvous Test (DART) probe, slammed into a small asteroid 7 million miles (11 million kilometers) from Earth tonight (Sept. 26) in what the U.S. space agency has billed as the world's first planetary defense test. The goal: to change the orbit of the space rock — called Dimorphos — around its larger asteroid parent Didymos enough to prove humanity could deflect a dangerous asteroid if one was headed for Earth.

"As far as we can tell, our first planetary defense test was a success," said Elena Adams, DART's mission systems engineer here at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUAPL), after the successful crash. "I think Earthlings should sleep better. Definitely, I will."

That's something the dinosaurs couldn't do 65 million years ago, when the massive Chicxulub asteroid slammed into the Yucatan Peninsula and led to their extinction.

"The dinosaurs didn't have a space program to help them, but we do," Katherine Calvin, NASA's chief scientist and senior climate advisor, said before the crash. "So DART represents important progress in understanding potential hazards in the future and how to protect our planet from potential impacts."

Related: 8 ways to stop an asteroid: Nuclear weapons & Bruce Willis?

The golf cart-sized DART spacecraft slammed into Dimorphos at 7:14 p.m. EDT (2314 GMT) while flying at a whopping 14,000 mph (22,500 kph). The spacecraft wasn't large as probes go, but NASA hoped that its 1,320 pounds (600 kilograms) would be enough to move the 534-foot-wide (163 meters) Dimorphos a bit faster in its orbit around its parent.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The spacecraft is very small," said planetary scientist Nancy Chabot, DART coordination lead at JHUAPL, which oversees the mission for NASA, before the impact. "Sometimes, we describe it as running a golf cart into the Great Pyramid."

Despite the on-target crash, there was a mix of calm and anticipation at DART's mission control center at JHUAPL as the spacecraft sped towards its destruction. Nothing went wrong during the crash, so engineers didn't have to try one of the 21 different contingency plans they had in their hip pocket.

Much of DART's last four hours were automated, with the spacecraft's navigation system locking on to Dimorphos in the final hour of its approach. DART's main camera beamed a photo to Earth every second until the feed went black as the spacecraft crashed into the asteroid.

"It's nerve-wracking," Andy Cheng, chief scientist for planetary defense at JHUAPL, said of the final days before the crash. He came up with the DART mission's concept in 2011. The $313 million DART mission launched on Nov. 23, 2021.

As DART closed in on Dimorphos, the asteroid transformed from a mysterious bright dot into a detailed landscape of boulders, crags and shadowed terrain. Then, right on time, the live feed from DART went black and flight controllers inside DART's mission operations center jumped for joy and traded hugs and high fives in a triumphant celebration. DART hit its asteroid bull's-eye.

"I think all of us were kind of holding our breath," Adams said, adding that it was like feeling "terror and joy" at the same time. "I'm kind of surprised none of us passed out."

A spacecraft crash for planetary defense

The DART mission is the first demonstration of what NASA calls a "kinetic impactor" for planetary defense: crashing a spacecraft into an asteroid to change its orbit. It's a basic method to protect the Earth if a potentially dangerous asteroid were spotted five or 10 years before a prospective impact.

"We are changing the motion of a natural celestial body in space. Humanity has never done that before," said Tom Statler, NASA's DART program scientist. "This is stuff of science fiction books and really corny episodes of 'Star Trek' from when I was a kid, and now it's real."

The risk of a catastrophic asteroid impact on Earth is remote, but real, NASA scientists have said. NASA has found about 40% of the large asteroids as wide as 500 feet (140 meters) that could pose a threat to the Earth and regularly scans the sky for more. NASA is also developing a new space telescope sentinel called the Near Earth Object Surveyor specifically designed to seek out hazardous asteroids in the solar system. That mission could launch by 2026.

But humanity also needs to have methods to deflect a hazardous asteroid should one be detected. Hence DART. "We're really excited every time our space missions protect life on Earth," Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA's associate administrator for science, told Space.com this morning.

NASA picked Dimorphos, a moonlet of Didymos, for the DART impact for a few reasons. First, the moonlet is part of a binary system and orbits its parent once every 11 hours and 55 minutes, a short enough time that any change in its orbit should be apparent in ground-based telescopes in follow-up observations.

Didymos and Dimorphos were discovered in 1996 and 2003 respectively and are the first binary asteroid system to be studied in detail. Using a binary asteroid system, rather than a solitary asteroid, meant that NASA could use a single spacecraft supported by ground telescopes to measure the asteroid deflection, instead of requiring an expensive second spacecraft, Cheng said.

While classified as a "potentially hazardous asteroid," Didymos and Dimorphos poses no threat of impacting Earth in the foreseeable future, which NASA measures in decades and centuries. DART was expected to accelerate Dimorphos just about 10 minutes faster in its orbit around Didymos, posing no risk of changing the binary system's orbit to come anywhere near Earth.

And at just 7 million miles away, Didymos and Dimorphos are at their closest to Earth that they'll be for the next 40 years. It takes a signal just 38 seconds to make the one-way trip from the DART to the Earth, NASA has said.

"So it's the right asteroid at the right time, and that time is now," Chabot said.

Dimorphos is also in the sweet spot for astronomers in that its size is similar to those asteroids NASA is most worried about for Earth impacts. It's also what NASA calls an S-type asteroid, a rocky variety that is one of the most common asteroid types in our solar system.

"We do think something like DART would be big enough to divert a Dimorphos-size asteroid," planetary scientist Mallory DeCoster, a modeler with DART's impact working group at JHUAPL, told reporters in the hours before impact.

Still, DART is a first-of-its kind mission and mission scientists didn't know exactly what to expect at Dimorphos. Is the asteroid a solid massive rock or more of a sandy rubble pile? And what was its exact shape? Variables like those can determine how effective a DART-like asteroid deflection will be.

During DART's final moments, photos from the spacecraft revealed stunning details of both Didymos and Dimorphos. The moonlet had never been seen before. DART revealed it as a strange new world, an egg-shaped asteroid covered in boulders and uneven terrain.

"It really looks just amazing," said Carolyn Ernst, DART's DRACO camera instrument scientist at JHUAPL. "It's like adorable! It's this little moon. It's so cute."

Angela Stickle, the leader of DART's impact working group at JHUAPL, said the team's simulations and models suggest the spacecraft would likely create a crater up to 65 feet (20 m) wide.

"We do expect it to fragment quite catastrophically," Stickle said of the DART spacecraft when it hit its target. "There is certainly the possibility that pieces of DART may be left on Dimorphos."

More: NASA's DART asteroid-impact mission explained in pictures

Just hitting Dimorphos was a feat of engineering, NASA said, with the DART spacecraft sending a photo every second as it closed in on its target.

The spacecraft also had witnesses to its demise. In the weeks before the impact, DART released a small cubesat called LICIACube to follow in its wake and observe the asteroid crash. The photos from that cubesat should reach Earth in the days after the impact and reveal closeup images of the impact and the ejecta it kicked up from Dimorphos.

Did humanity's first planetary defense test succeed?

Other spacecraft also watched the crash.

NASA's new James Webb Space Telescope, the Hubble Space Telescope and the Lucy spacecraft on its own asteroid mission all tracked the crash from their respective vantage points across the solar system. On Earth, a vast network of ground-based telescopes were trained on the event and will be following the binary Didymos-Dimorphos system over time to see how much faster Dimorphos is now moving in its orbit.

"Our requirements are for 73 seconds but we actually think we're going to change by about 10 minutes," Statler said.

It will take time to know if the DART impact was successful as a planetary defense test.

More than three dozen telescopes around the world, including at least one on every continent, will be tracking the Didymos-Dimorphos asteroid system over the next six months to understand exactly how effective the test was. The first radar observations of the impact could come as early as Tuesday (Sept. 27), said Cristina Thomas, a planetary scientist with Northern Arizona University who leads the DART observations working group.

"We're going to be observing Didymos until it's no longer observable," Thomas said. DART mission scientists added that they should know definitively how much DART moved Dimorphos in the next two months.

The observation campaign has brought in volunteer student and university groups around the world, each hoping to add their observations to the DART effort.

"There is a lot of them," Thomas said of the number of ground-based telescope teams. "It's very exciting to have lost count."

The European Space Agency is planning its own mission to the Didymos-Dimorphos asteroid system to follow up on DART's impact. That mission, called Hera, will launch a spacecraft to the asteroid in 2024 and actually orbit the binary asteroid system by 2027 to study the space rocks and the crater on Dimorphos created by DART.

"The technology of hitting the asteroid is really a challenge," Chabot told reporters hours before the crash. "But there is a lot that happens after that."

Editor's note: This story was updated at 9:09 p.m. EDT with new comments from DART mission scientists after its successful crash into an asteroid.

Email Tariq Malik at tmalik@space.com or follow him @tariqjmalik. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Instagram.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tariq is the Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001, first as an intern and staff writer, and later as an editor. He covers human spaceflight, exploration and space science, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Managing Editor in 2009 and Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. In October 2022, Tariq received the Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting from the National Space Club Florida Committee. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times as a kid and a fifth time as an adult. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast with space historian Rod Pyle on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.