NASA's Geotail spacecraft ends 30-year mission studying Earth's magnetosphere

The failure of the Geotail's final data recorder has forced its mission to end after 31 years in orbit.

After almost 31 years in space studying the protective magnetic bubble that surrounds Earth known as the magnetosphere, NASA's Geotail mission has come to an end.

Geotail's second data recorder, which had been gathering data about the structure and dynamics of our planet's magnetosphere, failed on June 28, 2022. The spacecraft's first data recorder had failed 10 years previous to this in 2012.

Attempts were made to repair the data recorder remotely which subsequently failed, forcing the joint mission with the Japanese Space Agency (JAXA) to draw to a close on Nov. 28, 2022. NASA announced the end of the mission in a statement on Jan. 18.

Related: Earth's magnetic field: Explained

Don Fairfield, emeritus space scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, was the first NASA's first project scientist for Geotail working on the mission until his retirement in 2008.

"Geotail has been a very productive satellite, and it was the first joint NASA-JAXA mission," Fairfield said in the statement. "The mission made important contributions to our understanding of how the solar wind interacts with Earth's magnetic field to produce magnetic storms and auroras."

Since its launch on July 24, 1992, Geotail's elongated orbit has taken it as far out as 120,000 miles from Earth and allowed the spacecraft to dip in and out of the magnetosphere, collecting information about the physics there. This cavalcade of data became the foundation of thousands of scientific papers.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The magnetosphere is vital to life on Earth as it traps potentially harmful charged particles in the solar wind in field lines, forcing them to travel around the Earth and pass back out into space its wake. These particles carry so much energy that they could strip away a planet's atmosphere and cause it to lose its water content to space as vapor, were they not blocked by a magnetic field.

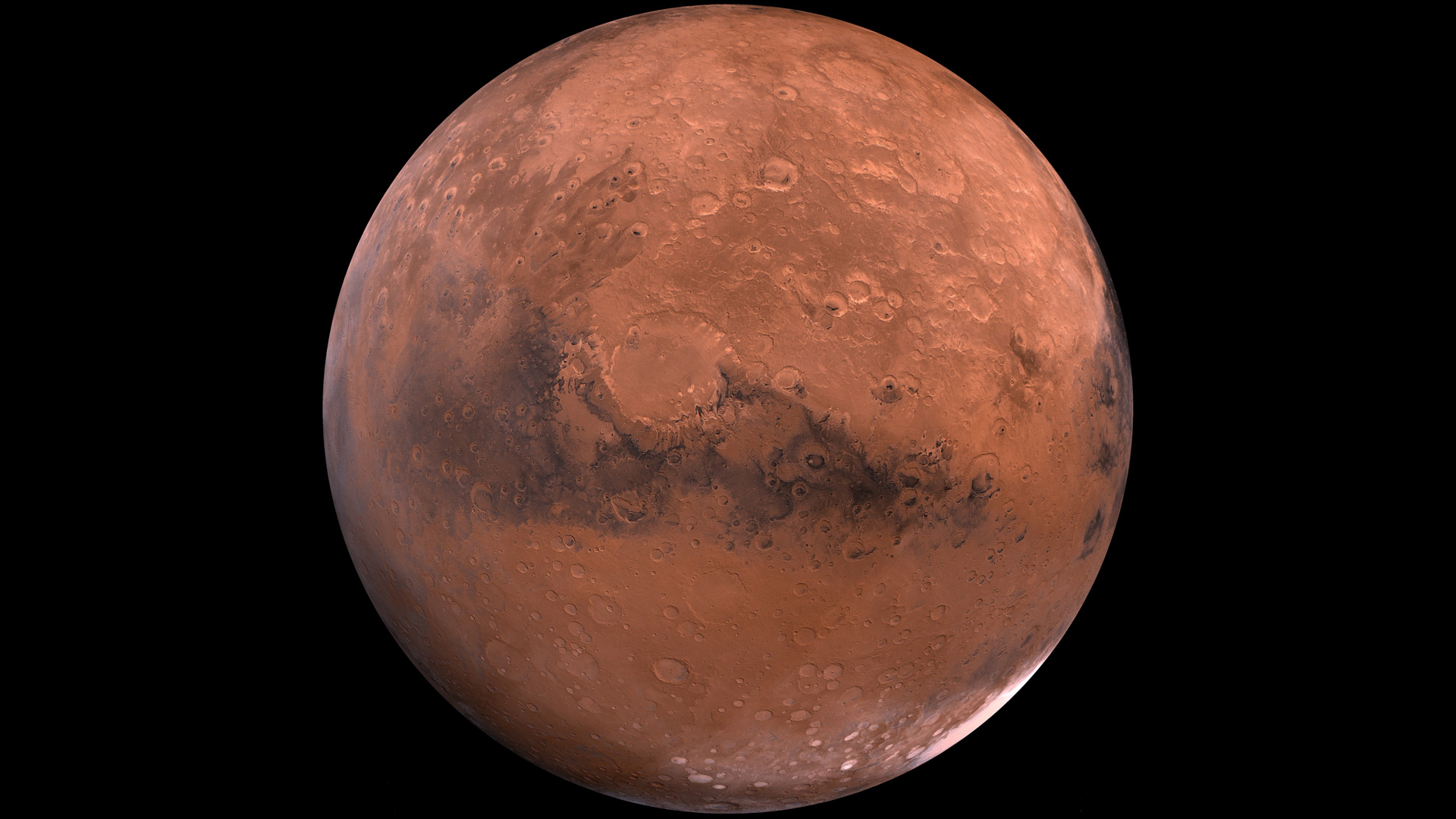

Many scientists believe that the reason Mars is now a barren and arid planet that cannot support life is that it lost its own magnetic field around 4 billion years ago, in turn causing the loss of much of its water.

In addition to allowing researchers to study how charged particles and energy from the sun reach Earth's magnetosphere, Geotail also revealed the speed at which charged particles in solar winds hit this magnetic field.

Geotail was also responsible for identifying the location in the magnetosphere where magnetic reconnection takes place. This is significant because this phenomenon is responsible for passing energy and material from the sun toward Earth and helps to create auroras, the beautiful light shows seen in the sky.

Away from Earth, the spacecraft was able to study the moon and successfully identified elements like oxygen, silicon, sodium, and aluminum in the lunar atmosphere.

Throughout its three decades of operation, the Geotail mission also aided other NASA space projects by providing data about remote regions of the magnetosphere which helped paint a picture of how events in one area of this magnetic bubble influence the physics of another region.

Geotail well exceeded its expected lifetime in space. The initial mission was only set to last for 4 years but went on to be extended several times.

Though Geotail's data-collected mission has drawn to a close, the science its operations have inspired and thus its legacy is far from done. Teams of scientists will continue to examine the data the craft has collected since 1992 using it to continue their research over the coming years.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, or on Facebook and Instagram.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.