The Lunar South Pole Is a Rich Target for NASA's 2024 Moon Goal

It has the potential for water and intriguing science.

When Vice President Pence challenged NASA to put humans on the moon by 2024 during an announcement last week, he targeted the southern lunar pole, an area rich in water as well as science.

Landing at that site might help astronauts' long-term survival on the moon and could possibly lay the groundwork for boosting future teams farther out into the solar system.

"We have known that the poles of the moon were unique environments for some time," Noah Petro, a NASA lunar astronomer in Greenbelt, Maryland, told Space.com by email. Petro is a project scientist for NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) mission currently orbiting Earth's nearest neighbor. Observations from LRO and other spacecraft have confirmed that there's water ice hidden in craters at the lunar south pole. Polar water or ice could provide both air and fuel as well as water for astronauts to drink.

Related: The Search for Water on the Moon in Pictures

Exploring "the south pole, with the possibility of water and/or ice, has the added benefit of finding a resource for future use," Petro said.

Why south pole?

When Apollo astronauts visited the moon 50 years ago, it was considered dry and barren. But the samples they returned eventually told a different story. In recent years, scientists have found "significant amounts" of hydroxyl — a chemical that includes both components of water — in the moon rocks brought home by Apollo 15, 16 and 17 astronauts.

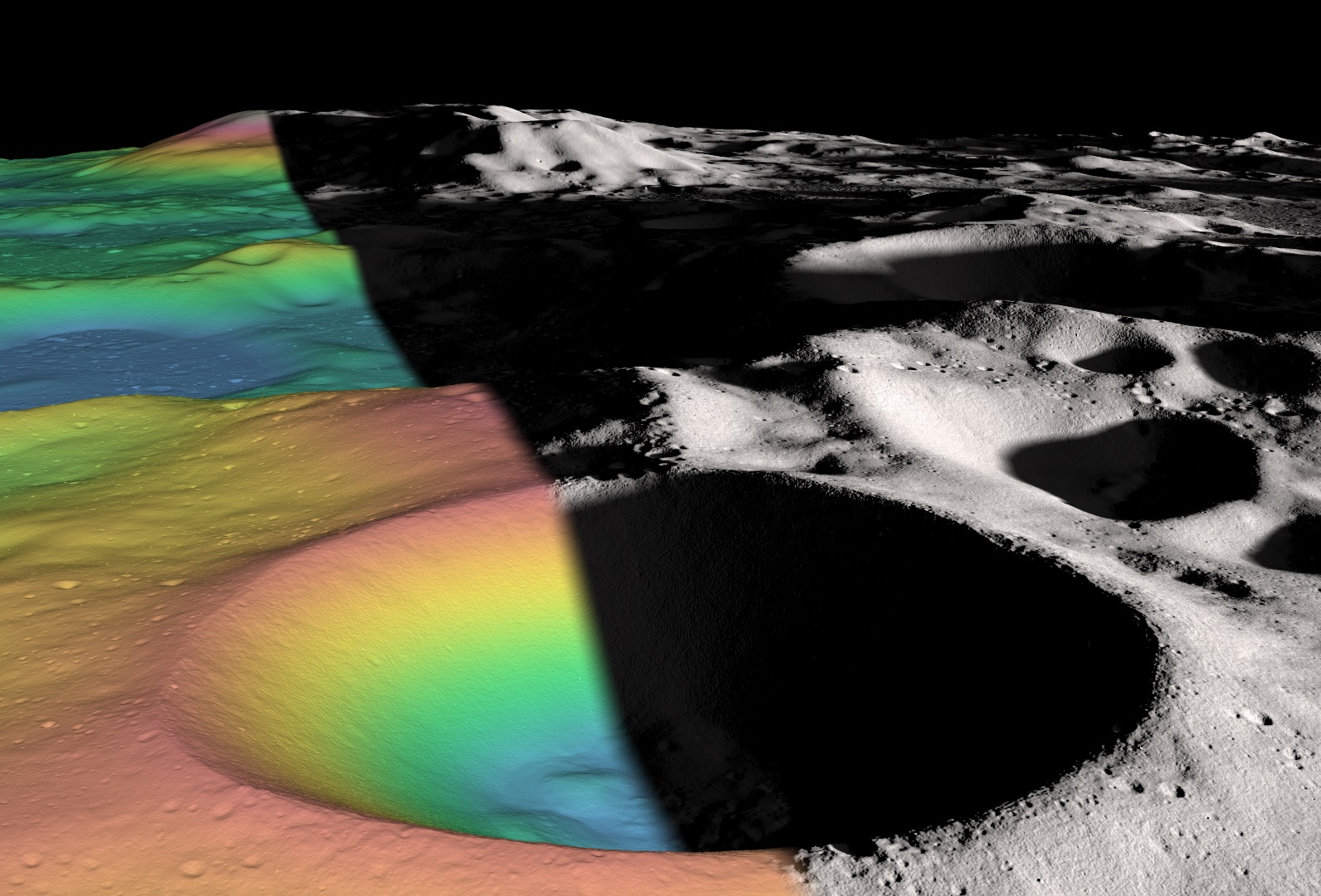

While water may be widespread beneath the lunar surface, the last decade or so has revealed that the permanently shadowed regions of the poles hide hydrogen-rich deposits, in some cases confirmed to be water ice, beneath the upper three feet (one meter) of the lunar regolith.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

While water is a requirement for humans to survive, a cool drink of lunar water isn't the only reason ice could be valuable. Once processed, the oxygen could produce vapor that could be used to supply a needed part of astronauts' breathable atmosphere. It could also be separated into hydrogen and oxygen components to be used as rocket fuel.

"These resources mined from the moon could potentially reduce the need for launching resources from Earth, which can significantly reduce the cost of deep space exploration," Debra Needham, a planetary scientist at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, told Space.com.

There is already an ongoing discussion about using the moon as a jumping-off point for Mars. By processing lunar ice into fuel, mission planners could help reduce the amount of material lifted into space from Earth, helping drive down costs. That, in turn, could help further human exploration beyond our planet.

"The farther humans venture into space, the more important it becomes to manufacture materials and products with local resources," Petro said.

Before you visit

There are still a number of things that need to be done before humans put boots on the moon again. While water-rich material has been identified at the lunar poles, scientists still want to nail down how much of it might be water and how much is ice.

"LRO has done an amazing job of telling us that there is something interesting going on there, but we should know more before sending humans," Petro said.

Needham agrees, adding that a lot of uncertainty remains about the distribution and purity of the water-rich material — information that could affect how it is extracted and used.

Related: How NASA Hopes to Mine Water on the Moon

The technology to turn water into fuel is still in its infant stages. One of the cubesats selected to join NASA's Space Launch System (SLS) on its first flight will rely on a water-electrolysis propulsion system. Zapping the water with electricity breaks the bonds between hydrogen and water, creating a readily combustible fuel for the satellite. Once in space, the tiny satellite will test the process in microgravity.

Another problem for human explorers is dealing with the lunar day, which is 14 Earth days long. Additionally, the sun will sit extremely low in the sky at the poles, casting deep shadows over the course of the day. Needham said that such shadows would cause wide temperature swings, block communication pathways and complicate the operation of some instruments that astronauts might carry with them.

"These challenges require creative solutions that, while achievable, require additional help from orbiting assets," Needham said, adding that they could drive up the costs and complexities involved in planning a mission to the lunar poles. But that doesn't mean that such missions wouldn't be worth it.

"The knowledge and resources we stand to gain by surmounting these challenges is vast," Needham said.

Before setting up a permanent lunar outpost, engineers must also develop sustainable exploration setups that would safely allow astronauts to escape Earth, travel to the moon, move from orbit down to the surface and return home safely. NASA would also have to establish long-term assets for lodging and mobility as well as sample collection and storage. Needham said that NASA is working its way through many of these challenges, in part through its work with the SLS as well as working with international partners on other components. The results will help astronauts not only explore the moon but also move out farther into the solar system.

"There is certainly still work to be done, but we are on our way to exploring new parts of the moon and proving our capability of exploring other deep-space destinations as we push on to Mars," Needham said.

- Trump's 'Back to the Moon' Directive Leaves Some Scientists with Mixed Feelings

- US Is in a New Space Race with China and Russia, VP Pence Says

- NASA Aims to Accelerate SLS Megarocket for 2024 Moon Push

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd