How will NASA deal with the moon dust problem for Artemis lunar landings?

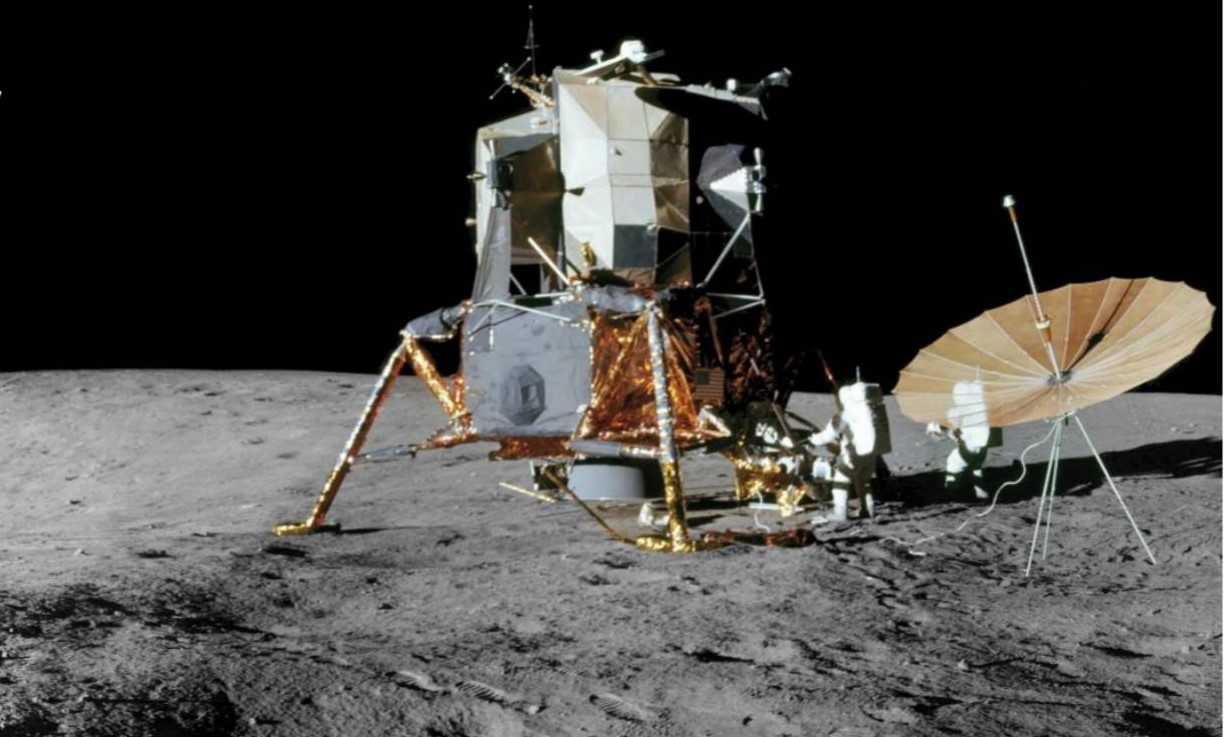

The Apollo experience holds many lessons.

Study teams have gone back to look at Apollo lunar landing data to appraise how much moon terrain was ejected into space.

Not only did Apollo landing crews get fogged out by the blown dust, making touchdowns troublesome, but substantial amounts of rock and debris were also sent flying during the rocket-powered landings.

NASA aims to put astronauts on the moon again by 2024, so what to do about the dust problem? Scientists are trying to devise the workarounds that appear needed if traveling to the moon is to become routine.

Related: Lunar legacy: 45 Apollo moon mission photos

Apollo memories

First, there are several historical accounts concerning safe touchdowns of humans on the moon, starting with the very first Apollo lunar landing, in July 1969. As Neil Armstrong, commander of the Eagle lunar module, reflected in a technical debrief, "at something less than 100 feet, we were beginning to get a transparent sheet of moving dust that obscured visibility a bit. As we got lower, the visibility continued to decrease."

Similarly, on Apollo 12, Pete Conrad ran into so much dust that he was blinded as he made his final descent to the surface. He later recounted that "the dust went as far as I could see in any direction and completely obliterated craters and anything else … I couldn't tell what was underneath me. I knew I was in a generally good area and I was just going to have to bite the bullet and land, because I couldn't tell whether there was a crater down there or not."

Several follow-on Apollo landing commanders noted similar concerns.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Making for a bad day

NASA hopes to apply the lessons from the Apollo era to future lunar missions.

"To paraphrase an old bromide, those who forget the past are doomed to land like it," said Chirold Epp, project manager for the Autonomous Landing and Hazard Avoidance Technology at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston.

"Having looked at the Apollo landings, I have come to two conclusions: One, those crews did a great job. Two, data from several of the landings support the idea that we must give future moon landers more information to increase the probability of mission success," Epp added.

Epp said that if a lunar module came to rest at an angle beyond 12 degrees, the astronauts might not be able to launch themselves off the surface. "So, if a crew landed on a hill or with a footpad or two on a large rock or in a crater, that could make for a bad day," he said.

Physics of rocket exhaust

"The moon is a low-gravity and airless body, which makes the rocket plume effects very different than what we experience on Earth," said Philip Metzger, a planetary scientist at the Florida Space Institute at the University of Central Florida (UCF) in Orlando.

"On Earth, rocks travel the farthest, while dust is stopped just a short distance away by the drag of Earth's atmosphere," Metzger told Space.com. "On the moon, it is the exact opposite, with the dust going the fastest and farthest. The dust can cause severe damage to the surfaces of materials if we land too close to other hardware on or orbiting the moon."

Lunar lander engine exhaust blows dust, soil, gravel and rocks at high velocity and will damage surrounding hardware — such as lunar outposts, mining operations or historic sites — unless the ejecta are properly mitigated, Metzger said.

Over the past 20 years, researchers have developed a consistent picture of the physics of rocket exhaust blowing lunar soil, "but significant gaps exist," Metzger said. "No currently available modeling method can fully predict the effects. However, the basics are understood well enough to begin designing countermeasures."

Related: Moon rush: private lunar lander plans

Wanted: launching pads

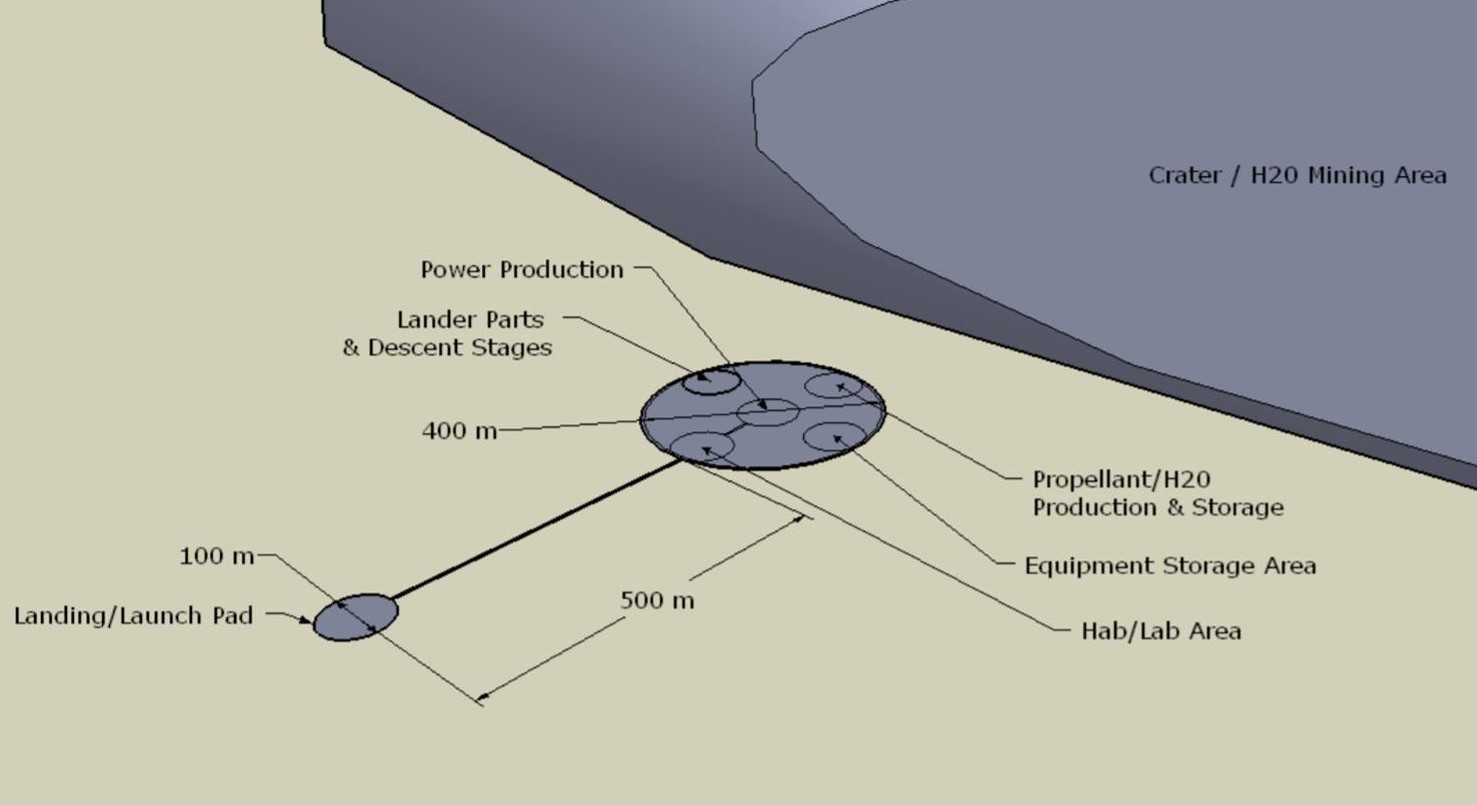

Metzger and other team members at UCF's Center for Lunar and Asteroid Surface Science (CLASS) say landing pads are needed for missions that repeatedly visit a lunar outpost.

For lunar landings, CLASS research has shown that the sandblasting that will occur at a lunar outpost is unacceptable, as it will excessively degrade optics, solar cells, thermal control surfaces and moving joints on mechanisms. Impacts of blowing rocks could also break hardware.

Florida Space Institute rsearchers are investigating methods to mitigate the effects of these blasts, such as sintering lunar regolith. They're also looking at robotics for bulldozing and building berms, as well as considering the use of gravel or pavers. And they're organizing a series of robotics competitions for landing pad construction technologies in conjunction with machine learning firms to further advance the necessary robotics capabilities.

"NASA takes the potential ejecta issues associated with rocket engine plume surface interaction very seriously," said Robert Mueller, senior technologist and principal investigator in the Exploration Systems and Development Office at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

That's for good reason, Mueller said; future human landers will have more issues with plume effects than Apollo landers because of higher engine thrust. NASA researchers are developing concepts for lunar landing and launchpads for crewed landers as well.

The space agency is currently taking steps to evaluate the potential effects in a lunar vacuum environment, Mueller told Space.com, with new computer modeling codes that have been under development through NASA's Small Business Innovation Research and Small Business Technology Transfer programs.

Caught on camera

There has not been any concerted effort to mitigate the lunar dust problem, ever, said Michelle Munk, entry, descent and landing system capability lead at NASA's Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. "We have a 'production' code to predict what will happen — but it is not validated with data, so we really don't know how good the predictions are."

Munk said it is especially challenging to run a realistic ground test for the lunar environment, which would provide good "truth" data. NASA's Space Technology Mission Directorate recently started a project that has both ground-testing and computational-modeling components.

Additionally, Munk is the principal investigator for four stereo cameras that will be carried on board Intuitive Machines' Nova-C lunar lander, which is scheduled to launch in 2021 on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket under NASA's Commercial Lunar Payload Services program. The payload is called Stereo Cameras for Lunar Plume-Surface Studies (SCALPSS).

SCALPSS is being developed at NASA Langley and leverages camera technology used on the agency's Mars 2020 rover Perseverance, Munk said. The camera cluster will capture video and still-image data of the lander's plume as the plume starts to impact the lunar surface until after engine shutoff, which is critical for future lunar and Mars vehicle designs, she said.

- Moon dust could be a problem for future lunar explorers

- NASA's 17 Apollo moon missions in pictures

- Moon rush: NASA wants commercial lunar delivery services to start this year

Leonard David is the author of the book "Moon Rush: The New Space Race," published by National Geographic in May 2019. A longtime writer for Space.com, David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

OFFER: Save at least 56% with our latest magazine deal!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.

-

rod ReplyAdmin said:Scientists and engineers are trying to work out ways to tamp down lunar dust so billowing clouds don't pose a problem to astronauts landing on the moon in 2024.

How will NASA deal with the lunar dust problem? : Read more

Other reports show the lunar dust from the Apollo missions is like tiny daggers and knives that can hurt your lungs too if the dust is brought inside and breathed. -

eagle6117 Here's a wild idea. If we can launch rovers to Mars that unpack themselves, then it stands to reason we can launch a landing pad. Why not send multiple rockets to the moon with pieces of a mobile landing pad? I can think of a few designs for this. In the end you'd have a flat surface which in turn would keep lunar dust from shooting up all around the lander.Reply -

Underdog Reply

The whole time i'm reading this I'm thinking of much the same thing. Send up automated unfolding land and launch platforms that self level and stabilize. Duh!eagle6117 said:Here's a wild idea. If we can launch rovers to Mars that unpack themselves, then it stands to reason we can launch a landing pad. Why not send multiple rockets to the moon with pieces of a mobile landing pad? I can think of a few designs for this. In the end you'd have a flat surface which in turn would keep lunar dust from shooting up all around the lander. -

Yargnad Why not just send an array of sensors up ahead of time that can auto pilot the lander safely with assistance from the pilot? Could use a variety of sensor types to generate telemetry for this purpose.Reply -

dfjchem721 Seems like a bare-bones rocket with a guidance system could be used to "pre-clean" landing sites. Such a "Landing Site Cleaner" (LSC) could also be a rudimentary lander that hovers over a future landing site (i.e. one for more advanced systems), cleans the site with its exhaust, then keeps sufficient fuel to land the LSC nearby to perhaps provide precision radio guidance to the now large clean site for any future mission, etc. The LSC could be powered by a simple RTG and offer other data, such as local "weather" conditions, etc., in case of some incident(s) which has altered the local landing site condition. One never knows.Reply

Of course orbiters would also be scanning such cleaned sites for their surface characteristics, etc. prior to their future use. Conduct enough of these LSC operations in advance of any missions and the dust will be settled by the time it is needed. Cleaning a landing site rather than providing one makes for a solid area to land that is probably 10x larger than a landing pad, with a guidance system (and memory of the site's topography) right near by. -

zardos With respect to repeated landings and particulate ejection, I think the use of creators for targeted landing sites would provide a natural barrier between habitats and landing areas. Perhaps, the creator walls could be drilled into to create the "caves" which humans could build habitats within. Separate creators could provide for separate groups with separate missions thus enabling independent environments whom could rescue one another if the need arose.Reply

I think we should examine new landing techniques which do not involve propulsion against the surface of the moon; using propulsion only to leave the surface. This would cut the particulate ejection problem in half.

I must admit, I have no idea what kind of system would be possible in an environment without atmosphere. -

iconoclast Replyeagle6117 said:Here's a wild idea. If we can launch rovers to Mars that unpack themselves, then it stands to reason we can launch a landing pad. Why not send multiple rockets to the moon with pieces of a mobile landing pad? I can think of a few designs for this. In the end you'd have a flat surface which in turn would keep lunar dust from shooting up all around the lander.

Not enough. The dust gets on spacesuits, and everything else outside the habitat. What is kicked up by rockets is only a small source. And it is extremely dangerous and deadly, it is indeed like millions of tiny tiny daggers, cutting lung tissue, hinges, suits, skin, mechanical controls, etc etc. Everythng is abraided. -

Pogo Working on the moon, and presumably in the future, Mars and elsewhere, will require that everything and everyone go through a decon process much as HazMat workers do here, before entering habitable areas to remove the regolith. No more crawling in the LM and just taking off the spacesuit. And the spacesuits will really need redesign so that it can easily be donned and doffed by the user without two or three helpers like on the ISS.Reply -

iconoclast ReplyPogo said:Working on the moon, and presumably in the future, Mars and elsewhere, will require that everything and everyone go through a decon process much as HazMat workers do here, before entering habitable areas to remove the regolith. No more crawling in the LM and just taking off the spacesuit. And the spacesuits will really need redesign so that it can easily be donned and doffed by the user without two or three helpers like on the ISS.

Some of it will still get in and build up over the years. Mass and power will be at a premium always, so the system will not be too good. And, the dust will affect everything outside, all the hinges, hatches, seals, rovers, solar panels, rockets, etc etc. And especially the decon machines themselves - exposed to the dust and destroyed, then you are screwed. And, I believe NASA has spent about 10 years and hundreds of millions of dollars for a new lunar suit design with no results, so you can put paid to that idea.

Mod Edit - Language -

iconoclast ReplyUnderdog said:The whole time i'm reading this I'm thinking of much the same thing. Send up automated unfolding land and launch platforms that self level and stabilize. Duh!

10 billion dollars to get that mass to the surface of Mars, and a half decent chance it will crash leaving you nada. And it won't help with the bigger problem of dust from boots, wheels, and especially SANDSTORMS.