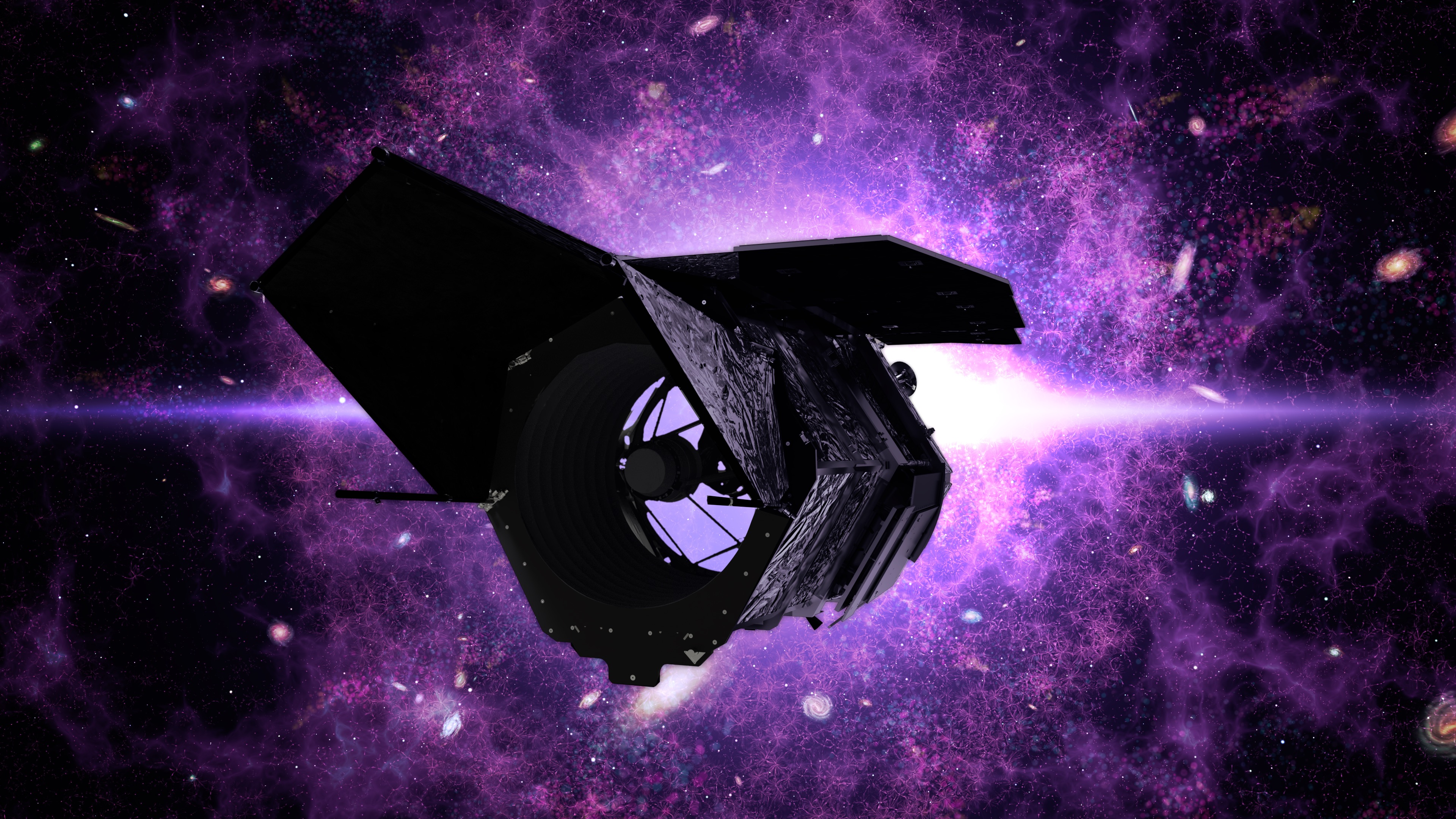

NASA's Nancy Grace Roman space telescope will send the hunt for exoplanets into warp speed

A new NASA space observatory could push planet-hunting forward at warp speed by gathering data up to 500 times faster than the venerable Hubble Space Telescope does.

The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope (formerly known as the Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope or WFIRST) passed a key ground-system design review this month, according to NASA. Roman, as the telescope is called in short, relies on technology that was originally built for spy missions on Earth. Instead, after its launch in the mid-2020s, Roman will spy on exoplanets across the galaxy, as well as many other cosmic phenomena.

Roman will be optimized for a kind of planetary survey called microlensing, which is an observational effect that happens when mass warps the fabric of space-time. At its most extreme, this kind of gravitational lensing is used to observe very massive objects such as galaxies or black holes. In miniature, however, microlensing creates enough "warping" in smaller stars and planets for planet-hunting.

Related: 7 ways to discover alien planets

At this smaller scale, microlensing happens when one star aligns closely with a second star, from the vantage point of Earth. The star that is closer to our planet focuses and amplifies the light from the star that is further away, allowing scientists to see it in a little more detail than usual. Even planets that are orbiting the foreground star can magnify the star's light, creating a spike in brightness.

Roman's microlensing capabilities will be coupled with a wide field of view that is 100 times larger than Hubble's, while capturing stars and planets with the same resolution as the famed telescope. NASA expects Roman to pick up more data than any of the agency's other astrophysics missions.

Roman's efforts will build on other NASA missions optimized for planet-hunting, including the past Kepler mission that found thousands of exoplanets and the current Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) looking for Earth-like planets close to us. Hubble, while not designed for planet-hunting since it launched just when discoveries were beginning, has done plenty of exoplanet science as well. Numerous observatories on Earth have found their own planets or confirmed observations made by space telescopes, creating a larger community of exoplanet science that Roman will contribute to after its launch.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"With such a large number of stars and frequent observations, Roman's microlensing survey will see thousands of planetary events," Rachel Akeson, task lead for the Roman Science Support Center at the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center at the California Institute of Technology, said in a NASA statement. "Each one will have a unique signature, which we can use to determine the planet's mass and distance from its star."

Gathering the data is one challenge. Parsing and understanding the information for discoveries and "lessons learned" is another. The ground systems supporting Roman will rely on cloud-based remote services and advanced analytical tools to make sense of the enormous amounts of data the telescope collects: Roman's design calls for the telescope to watch hundreds of millions of stars every 15 minutes for several months at a stretch.

Another notable change from previous flagship missions is the speed at which Roman's data will become public; NASA has promised to make all data available only days after observations are collected.

"Since scientists everywhere will have rapid access to the data, they will be able to quickly discover short-lived phenomena, such as supernova explosions. Detecting these phenomena quickly will allow other telescopes to perform follow-up observations," NASA added in the same statement.

Exoplanets and supernovas are not the only things Roman will discover. It will hunt for brown dwarfs, which are "failed stars" (objects much more massive than Jupiter that are not quite large enough to sustain nuclear fusion). Other expected astronomy targets include runaway stars and bizarre cosmic objects such as the neutron stars and black holes that are left behind when stars run out of fuel.

Roman will also join other observatories in trying to figure out the nature of dark matter and dark energy, which is impossible to observe except through monitoring effects on other objects. Roman's observations will allow the telescope collect precise measurements from numerous galaxies, mapping the distribution and structure of regular matter and dark matter across the universe's history.

Among other applications, Roman's work in dark energy and dark matter could help scientists understand why the universe is expanding, and why that expansion is accelerating as the universe gets bigger. That discovery of acceleration got an assist from Hubble in the 1990s, eventually leading to a Nobel Prize in 2011.

Another Roman partnership with its predecessor will be follow up on Hubble's Cosmic Assembly Near-infrared Deep Extragalactic Legacy Survey (CANDELS). This survey charted how galaxies develop over time; Hubble took 21 days to gather the information, but Roman will only take half an hour to conduct a similar investigation.

"With its incredibly fast survey speeds, Roman will observe planets by the thousands, galaxies by the millions, and stars by the billions," Karoline Gilbert, mission scientist for the Roman Science Operations Center at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, said in the same NASA statement. "These vast datasets will allow us to address cosmic mysteries that hint at new fundamental physics."

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.