Locust swarms are invading Africa. Here's how NASA satellites can help stop them.

Billions of locusts have been swarming throughout eastern Africa for months, ravaging crops and threatening the food source for millions of people in the region. Thankfully, NASA's Earth-observing satellites might be able to help.

Traveling locust swarms are common in Africa, southern Asia and the Middle East, but the insect population started getting out of hand in December 2019 when hundreds of millions of the voracious bugs invaded Kenya and decimated about 173,000 acres of cropland. The enormous swarms of locusts have since spread to 10 countries in Africa, putting millions at risk of going hungry, according to the United Nations (UN).

The UN said that "unusual climate conditions" have enabled the locusts to reproduce more rapidly, and that the arrival of the rainy season (from March through May) will likely make matters worse. Now, NASA is partnering with the UN to stop these locust swarms by better understanding the insects' relationship with Earth's climate.

Related: Striking photos of locust swarms (gallery)

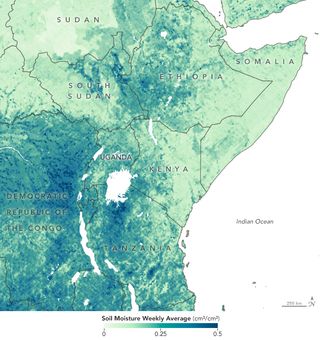

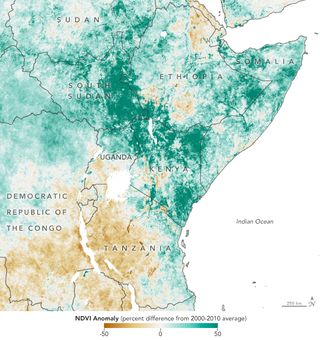

By monitoring soil moisture and vegetation from space using satellites, NASA scientists can learn how environmental changes affect locust populations and use that information to stop outbreaks before they start.

"The approach that helps prevent large-scale infestations is to catch the locusts very early in their life stages and get rid of their nesting grounds," Lee Ellenburg, the food security and agriculture lead for SERVIR at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center, said in a statement. SERVIR is a joint program between NASA and the U.S. Agency for International Development that's dedicated to improving environmental policies in developing nations with the help of satellite data.

Equipped with satellite data and imagery, the SERVIR team partnered with the UN's Desert Locust Information System and its Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) to learn more about the locusts' behavior. By combining satellite data with information about where, when and why locust swarms emerge, scientists have come up with a strategy to reduce their populations.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Adult locusts are hard to stop in their tracks because the insects can fly 30 to 90 miles (50 to 150 kilometers) in a single day. So, to thwart these disastrous locust outbreaks, scientists need to target locust eggs and young locusts — called "hoppers" because their wings have not yet developed — because they are less mobile and make easier targets.

"Once locusts lay the eggs and hatch, they start looking for vegetation to feed on," Catherine Nakalembe, a food security researcher with SERVIR and NASA Harvest, said in the statement. "They start migrating, looking for more to eat, and then keep multiplying."

Scientists know that locusts prefer to lay eggs in wet, warm soil and baby locusts need vegetation nearby to sustain them before their wings develop (once they have wings, they can forage across larger distances). By monitoring soil moisture and vegetation from space, satellite data can help researchers predict locust "baby booms" and nip these outbreaks in the bud.

"The data we have so far show a strong correlation between the location of sandy, moist soils and locust activity," Ashutosh Limaye, NASA's chief scientist for SERVIR, said in the statement. "Wherever there are moist, sandy locations, there are locusts banding or breeding." The locations determined to be prime breeding spots can then be sprayed with pesticides to stop the locust population from growing out of control.

"Our goal is to learn from FAO how to find out where the breeding grounds are," Ellenburg said. "If the prevailing conditions indicate that locusts will hatch and be taking off, the goal is to go early and destroy their nesting grounds."

Satellite data has shown that the Horn of Africa has recently been much greener than usual because the region received about four times the average amount of rainfall between October and December — which is the wettest "short rain season" the area has seen in four decades.

The extra rainfall created a wet environment where plants can thrive, thereby providing ideal breeding grounds for locusts as well. Now that the "long rain season" has begun, NASA is studying this satellite data to create forecasts of where and how additional locust outbreaks might occur.

- New weapon against desert locust plagues: satellite images

- How NASA satellites are helping to halt malaria outbreaks

- Ant attack! Insects swarm Australian ring-hunting telescope

Email Hanneke Weitering at hweitering@space.com or follow her @hannekescience. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save at least 56% with our latest magazine deal!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Hanneke Weitering is a multimedia journalist in the Pacific Northwest reporting on the future of aviation at FutureFlight.aero and Aviation International News and was previously the Editor for Spaceflight and Astronomy news here at Space.com. As an editor with over 10 years of experience in science journalism she has previously written for Scholastic Classroom Magazines, MedPage Today and The Joint Institute for Computational Sciences at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. After studying physics at the University of Tennessee in her hometown of Knoxville, she earned her graduate degree in Science, Health and Environmental Reporting (SHERP) from New York University. Hanneke joined the Space.com team in 2016 as a staff writer and producer, covering topics including spaceflight and astronomy. She currently lives in Seattle, home of the Space Needle, with her cat and two snakes. In her spare time, Hanneke enjoys exploring the Rocky Mountains, basking in nature and looking for dark skies to gaze at the cosmos.

Most Popular