NASA switches off Voyager instruments to extend life of the two interstellar spacecraft 'Every day could be our last.'

"The Voyagers have been deep space rock stars since launch, and we want to keep it that way as long as possible!"

NASA engineers are turning off two instruments to ensure that the twin spacecraft, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, can continue exploring space beyond the limits of the solar system.

To save energy for further interstellar exploration, mission engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) deactivated Voyager 1's cosmic ray subsystem experiment on Feb. 25. On March 24, they will shut down the low-energy charged particle instrument onboard Voyager 2.

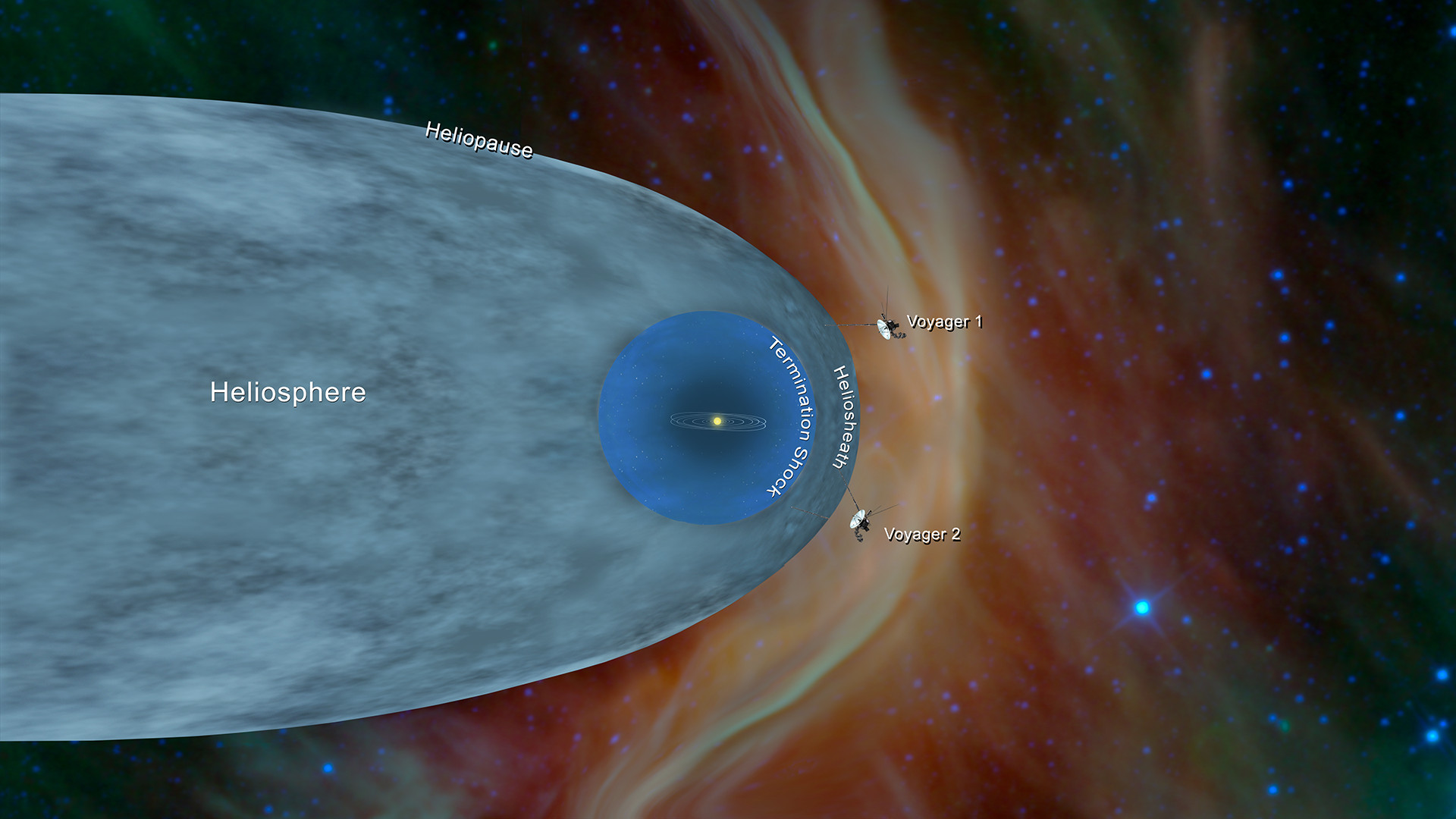

Launched in 1977 and carrying the same suite of ten instruments, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 reached interstellar space in 2012 and 2018, respectively. It is little wonder that Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are operating on dwindling power supplies. After all, the two spacecraft have traveled a combined 29 billion miles to become the farthest human-built objects from Earth.

"The Voyagers have been deep space rock stars since launch, and we want to keep it that way as long as possible," Voyager project manager at NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory Suzanne Dodd said in a statement. "But electrical power is running low. If we don’t turn off an instrument on each Voyager now, they would probably have only a few more months!"

Life beyond the solar system

Both Voyager spacecraft have a power system based on generating electricity from the heat emitted by the decay of a radioactive isotope of plutonium.

This radioisotopic power system loses around 4 watts of power from Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 each year. In the 1980s, several instruments aboard both spacecraft were turned off. This was because the Voyager twins had both completed their investigation of the solar system's giant planets, which boosted the longevity of both probes.

To conserve this power, NASA operators turned off Voyager 2's plasma science experiment in October 2024. The experiment aimed to measure how much plasma flows past it and in what direction. The Voyager 2 instrument had been collecting limited data in the years before its shutdown due to its orientation of Voyager 2 in relation to the flow of plasma beyond the solar system.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Voyager 1's own plasma science instrument stopped working correctly in 1980 and was turned off in 2007 to preserve power.

Most recently, NASA shut off Voyager 1's cosmic ray subsystem at the end of February. The data from the suite of three telescopes designed to study cosmic rays was integral in the Voyager science team's determination that Voyager 1 had exited the heliosphere, the sun's sphere of influence at the edge of the solar system.

Shutting down at the end of March is Voyager 2’s low-energy charged particle instrument, the role of which is to measure the various ions, electrons, and cosmic rays originating from the solar system and our galaxy.

"The Voyager spacecraft have far surpassed their original mission to study the outer planets," Voyager program scientist Patrick Koehn said. "Every bit of additional data we have gathered since then is not only valuable bonus science for heliophysics, but also a testament to the exemplary engineering that has gone into the Voyagers — starting nearly 50 years ago and continuing to this day."

— Voyager 1 is back online! NASA's most distant spacecraft returns data

— Voyager: 15 incredible images of our solar system (gallery)— Scientists' predictions for the long-term future of the Voyager Golden Records will blow your mind

— Voyager 1 spacecraft phones home with transmitter that hasn't been used since 1981

The fact that the Voyager spacecraft are the only two human-made objects to make it to interstellar space means that the data they collect is unique. Thus, the decision to switch off any instruments on either Voyager 1 or Voyager 2 isn't taken lightly. Shutting down these two instruments should grant both spacecraft another year of exploration before more instruments have to be turned off.

Both spacecraft have three operational instruments, dropping to two in 2026. It is hoped that Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 will carry one operational instrument into the 2030s. Unforeseen circumstances could arise and change these plans, though.

"Every minute of every day, the Voyagers explore a region where no spacecraft has gone before," Voyager project scientist at JPL Linda Spilker said. "That also means every day could be our last. But that day could also bring another interstellar revelation.

"So, we’re pulling out all the stops, doing what we can to make sure Voyagers 1 and 2 continue their trailblazing for the maximum time possible."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

-

Classical Motion It’s a shame we can’t develop a potential between the craft and a trailing wire for power, for dark space travel.Reply -

contrarian Reply

They should have made those RTGs much bigger.Classical Motion said:It’s a shame we can’t develop a potential between the craft and a trailing wire for power, for dark space travel.

Seems likely they did not expect these spacecraft to last so long. -

billslugg A trailing wire that generated power by crossing the local magnetic field would slow the craft. Some slowing might be acceptable.Reply

Voyagers are going 17 km/s or 1.7e4 m/s

A kilogram of mass at that speed has a kinetic energy of 1/2*m*V^2 joules or 1.4e8 joules. Each craft weighs 722 kg thus each has a total of 1e11 J. They each use 200 watts of power currently. A watt second will give one joule. Their kinetic energy is sufficient to power their instruments for 16 years. -

Classical Motion I would love to sample Voyager. For corrosion and mutation. Before and after photos. I doubt we could make an ocean buoy that would last that long. Or a balloon.Reply

We need to sample previous moon mission artifacts for analyses too. What kind of paint(protective covering) does a moon or space structure need?

How much damage does cosmic radiation do? What would it do to a generational garden?

Perhaps not as much as suspected.

As for space power, we need to live off the land. Some how. There is charge, electricity, moving thru space. If we can collect it. Or use it to rotate(charge) battery or capacitor banks. -

modelrocketman Reply

Agreed but I think the design parameters were to explore our Solar System and that was it. They weren't expected to last!! It was decided to keep going as ground stations got better. I read in aviation journals there was a time when the younger controllers stepping in didn't know the spacecraft's programming language as it was so old! Modern craft use different programming computer languages. They had to get older, retired controllers out of retirement to train the "new guys" It currently takes 22.5 hours one-way to get commands to Voyager II and 22.5 hours to receive an acknowledgement! An excellent example of the speed of light which is the same speed radio waves travel!! Example it takes 5 to 20 minutes for radio signals from Earth to hit Mars depending on the planet's positions relative to each other. This is cool stuff!contrarian said:They should have made those RTGs much bigger.

Seems likely they did not expect these spacecraft to last so long. -

contrarian Reply

Yes, the Voyagers used a version of Fortran (V) that is not used anymore. They were lucky to find the people who made these programs still around and helpful.modelrocketman said:I read in aviation journals there was a time when the younger controllers stepping in didn't know the spacecraft's programming language as it was so old!

But other Fortran variants are still used in a number of scientific computing apps.*

* https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fortran -

Hevach Making the RTGs bigger wouldn't have helped a whole lot unless the whole probe were made bigger and more robust. A lot of instruments just stopped being useful after Neptune. They've already passed far beyond the range of the low power antenna and even had to change how they communicate for the big antenna to work at this distance, and even if the RTG doesn't give out the antenna just won't be up to the job soon (possibly as soon as later this year for low end predictions). Multiple thrusters have failed, heaters have failed, memory units have failed, instruments have failed, almost everything is on backups (a few things are switched back to broken primaries because the backups are broken worse)... At this point more on the Voyagers has failed than is still working.Reply

The mission at this point is as much an exploration of long range engineering as it is a scientific mission. It's mission goal is for the signal to finally be lost in the noise, and it's in a tight race with the battery and the failure list which will happen first. -

billslugg Reply

I can't be of help here as I only learned Fortran IV.contrarian said:Yes, the Voyagers used a version of Fortran (V) that is not used anymore. -

contrarian Reply

Failures have certainly piled up, but from what I read some critical instruments to study interstellar space are still providing significant data, which is why they are powering down less critical systems. So yes, it may boil down to instrument failure in the end, but it looks as though one or both will run out of power before total instrument failure. Time will tell.Hevach said:The mission at this point is as much an exploration of long range engineering as it is a scientific mission. It's mission goal is for the signal to finally be lost in the noise, and it's in a tight race with the battery and the failure list which will happen first.

https://blogs.nasa.gov/voyager/2025/03/05/nasa-turns-off-2-voyager-science-instruments-to-extend-mission/#:~:text=Mission%20engineers%20at%20NASA%27s%20Jet%20Propulsion%20Laboratory,will%20continue%20to%20operate%20on%20each%20spacecraft. -

DanaBspaced Reply

Weight is always at a premium for a space craft. I imagine the RTGs were as large as they could manage.modelrocketman said:Agreed but I think the design parameters were to explore our Solar System and that was it. They weren't expected to last!! It was decided to keep going as ground stations got better. I read in aviation journals there was a time when the younger controllers stepping in didn't know the spacecraft's programming language as it was so old! Modern craft use different programming computer languages. They had to get older, retired controllers out of retirement to train the "new guys" It currently takes 22.5 hours one-way to get commands to Voyager II and 22.5 hours to receive an acknowledgement! An excellent example of the speed of light which is the same speed radio waves travel!! Example it takes 5 to 20 minutes for radio signals from Earth to hit Mars depending on the planet's positions relative to each other. This is cool stuff!