Uranus by 2049: Here's why scientists want NASA to send a flagship mission to the strange planet

A $4.2 billion mission to the seventh planet could change the way we see the solar system, scientists say.

A key committee of scientists has recommended that a flagship mission to Uranus should be NASA's highest-priority large planetary science mission for the next decade.

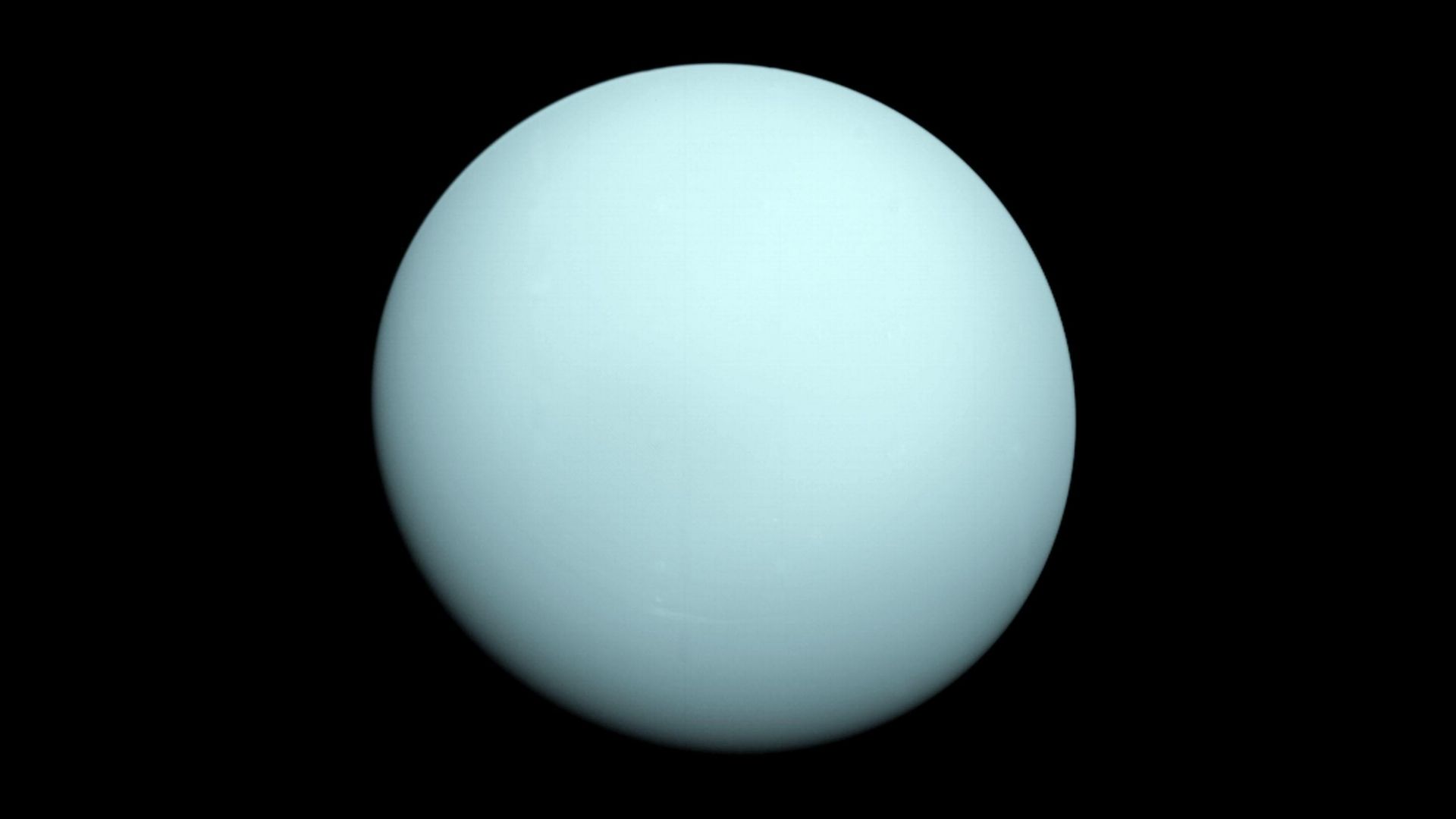

Uranus is a mostly unexplored world; NASA's only visit to the seventh planet was Voyager 2's brief fly-by on Jan. 24, 1986, during which scientists discovered some of the planet's rings and moons.

The new recommendation comes from a process called the decadal survey, which is led by the National Academy of Sciences and offers NASA guidance for prioritizing science goals. That committee's new report, published Tuesday (April 19), highlighted a mission concept called the Uranus Orbiter and Probe (UOP) for a multi-year orbital tour during which it should jettison an atmospheric probe. The committee called Uranus "one of the most intriguing bodies in the solar system" and targeted launch opportunities in the early 2030s for a 12- to 13-year cruise out to begin observations.

"When I first read that recommendation, I feared I might be dreaming!" Leigh Fletcher, a planetary scientist at the University of Leicester in the U.K. who participated in the decadal survey process, told Space.com. "This decadal survey prioritization is a wonderful leap forward for the outer solar system community."

Related: Voyager at 40: 40 photos from NASA's epic 'grand tour' mission

A new flagship mission

For now, the Uranus Orbiter and Probe isn't a specific mission, but a concept. The previous decadal survey, released in 2011, mentioned the idea as the third priority for a flagship mission, following ideas that matured into the Perseverance rover now at work on Mars and the Europa Clipper mission due to launch in 2024.

Other reports have also stressed the need for a fully-equipped Uranus orbiter, complete with an atmospheric probe to dive beneath the planet's clouds. The pre-Decadal Survey Ice Giants study report included a variety of options for Uranus and Neptune spacecraft, while a white paper called Exploration of the Ice Giant Systems also submitted to the decadal survey committee discusses the need for an orbiter/probe combo in a flagship-class mission.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

So it's perhaps no surprise that Uranus is now at the top of the agenda.

Lead author of the latter ice giants report is Chloe Beddingfield, a planetary scientist and astronomer at NASA'sAmes Research Center in California, who thinks that there's compelling broad planetary and even exoplanet science to be done at Uranus. "A flagship mission to the Uranian system will provide an incredible opportunity to explore how ice giant systems, which are common in the galaxy, formed and evolved," she told Space.com. That crossover with exoplanet science may have helped Uranus' cause.

The Uranus Orbiter and Probe mission will cost in the region of $4.2 billion, according to initial evaluations. Some scientists thought that a more affordable concept costing under $900 million would be the only way to get a Uranus mission off the ground. (NASA calls missions of this budget "New Frontiers" missions; examples include the Juno mission to Jupiter and the OSIRIS-REx mission to fetch an asteroid sample.)

"A New-Frontiers level mission could only just scratch the surface, unable to explore the full ice giant system in all its rich diversity," Fletcher said.

"To fully explore Uranus we need to be in orbit, exploring the interior, atmosphere and magnetosphere, and touring the myriad icy moons and rings," he added. "If it's worth doing, then it's worth doing properly!"

Getting there in time

How long it will take to reach Uranus depends on when a spacecraft launches. A gravity-assist from Jupiter is required for a larger spacecraft to avoid an unduly long journey. The giant planet's position means a Uranus mission would preferably launch in 2031 or 2032 to arrive at Uranus in 2044 or 2045. It could leave Earth as late as 2038, but that would mean a 15-year journey.

However, there's a good scientific reason to get to Uranus by 2045. A year on Uranus lasts 84 Earth years and Voyager 2 flew past during the southern hemisphere's summer, so if scientists want the most contrast with that mission's views then the new spacecraft needs to arrive before southern spring begins in 2049.

That timing would also give the probe all-new views of the southern hemispheres of Uranus' moons, intriguing worlds in their own rights.

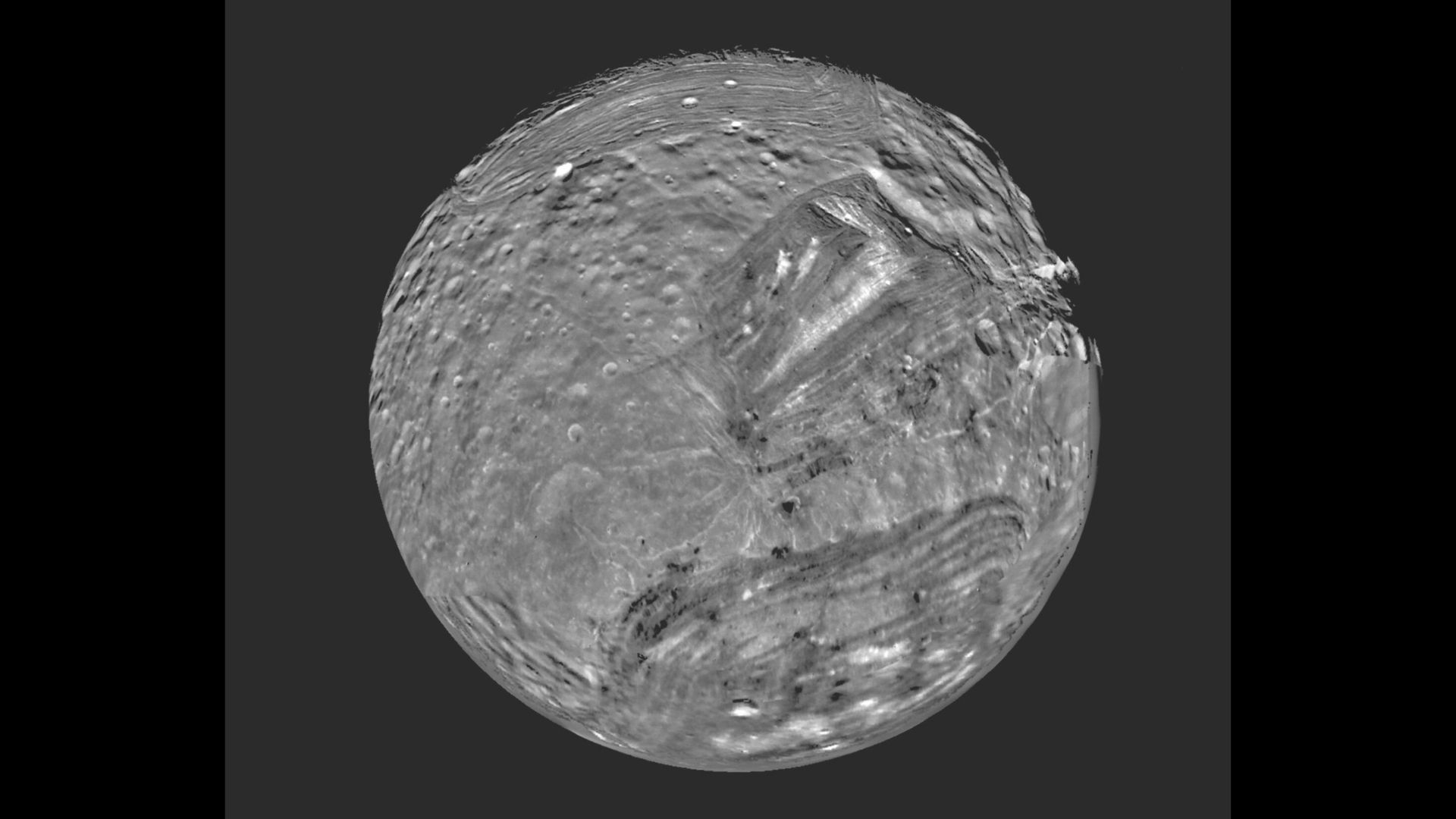

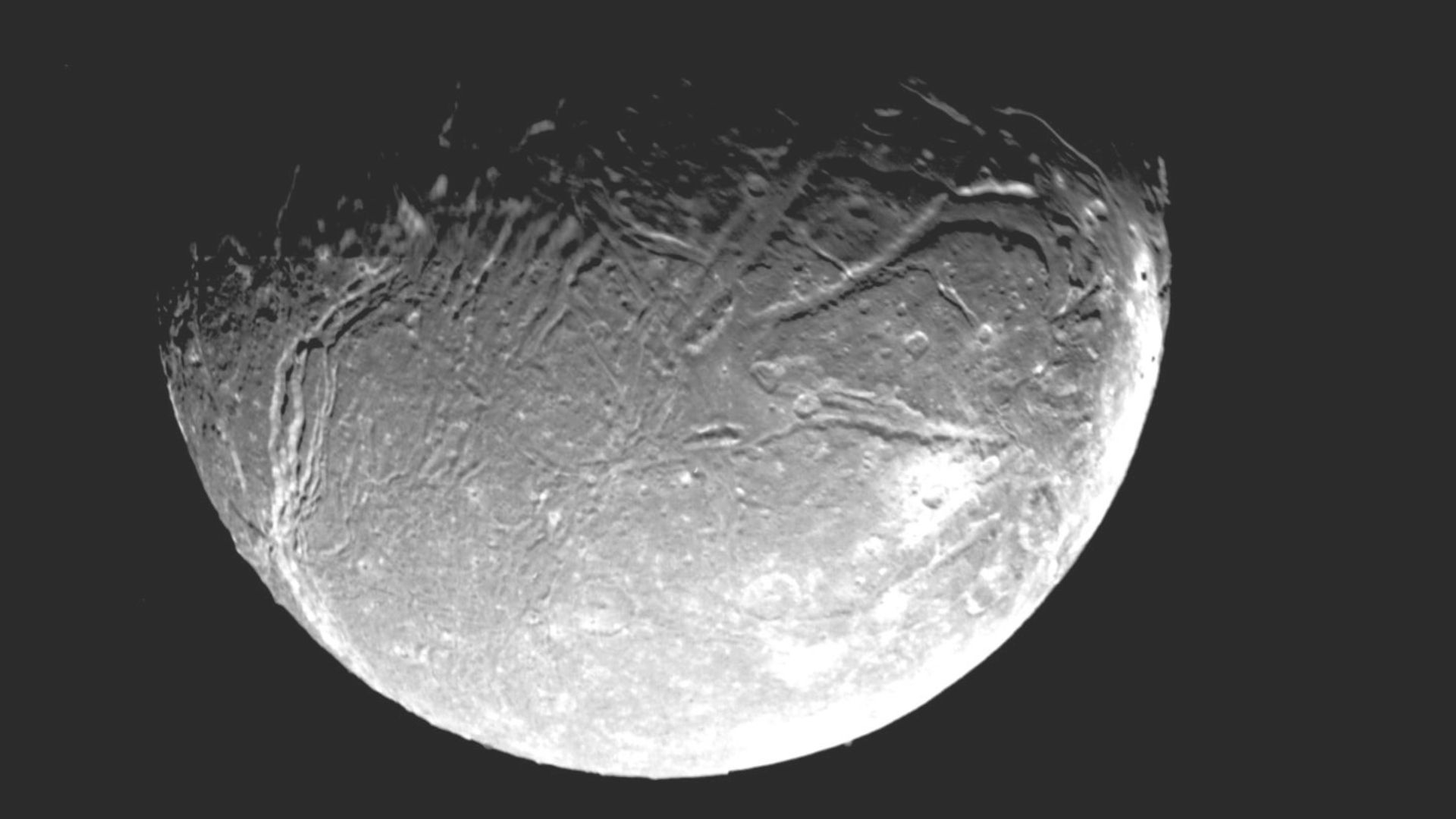

Uranus has 27 moons, but scientists think that its five largest moons — Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania and Oberon — may be ocean worlds that could possibly harbor life. "Investigation of these moons would enhance our knowledge of where potentially habitable bodies exist in our solar system," Beddingfield said. These moons are not covered in craters, which suggests they may be geologically active with changing surfaces, possibly because of ice volcanoes.

"Uranus' large moons are really weird," Richard Cartwright, a planetary scientist and astronomer at NASA's Ames Research Center and lead author of a paper proposing a Uranus Orbiter, told Space.com. He noted that Voyager 2's brief flyby captured snapshots of the moons' surfaces that showevidence for geologic activity on Miranda and Ariel in particular.

"However, the northern hemispheres of the Uranian moons were shrouded by winter darkness at the time of the flyby and were largely unimaged, leaving many unanswered questions about the origin and evolution of these icy bodies," he said. For now, Cartwright has arranged to use the recently-launched James Webb Space Telescope to search for chemicals that may have leaked out of internal oceans on these worlds, but that's no comparison to visiting up close.

The search for a name

The committee recommended that work on a true mission design should begin by 2024, budgets allowing, but any Uranus mission is going to need an iconic name.

"A good possible name for the orbiter is 'Caelus,' which is the Roman counterpart of the Greek god Uranus," Beddingfield offered. "This would be fitting because Uranus is the only planet in our solar sSystem named after a character from Greek instead of Roman mythology."

But there likely be two pieces of hardware: one orbiting satellite and one atmospheric probe. For comparison, NASA named its Cassini orbiter, which studied Saturn from 1997 to 2017, after the discoverer of Saturn's moons. The mission's European-built probe — which descended to the surface of the strange moon Titan — was named Huygens after the astronomer who confirmed Saturn has rings.

Another option could be "Shakespeare" for the Uranus orbiter and "Pope" for the atmospheric probe. After all, the moons of Uranus are named after characters from the works of William Shakespeare and the British poet Alexander Pope. For example, Ariel and Miranda feature in Shakespeare's "The Tempest" while Titania and Oberon are from his "A Midsummer Night's Dream."

"I think Shakespeare is a great option for the name of the mission," Cartwright said. "An inspiring name and well known!"

But although Uranus scientists are celebrating the new recommendation, a Uranus mission isn't yet a reality. "There are many hurdles to come — political, financial, technical — so we're under no illusion," Fletcher said. "We have about a decade to go from a paper mission to hardware in a launch fairing. There's no time to lose."

Jamie Carter is the author of "A Stargazing Program For Beginners" (Springer, 2015) and he edits WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com. Follow him on Twitter @jamieacarter. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jamie is an experienced science, technology and travel journalist and stargazer who writes about exploring the night sky, solar and lunar eclipses, moon-gazing, astro-travel, astronomy and space exploration. He is the editor of WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com and author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners, and is a senior contributor at Forbes. His special skill is turning tech-babble into plain English.