We finally know why NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft stopped communicating — scientists are working on a fix

The first spacecraft to explore beyond the solar system started spouting gibberish late last year. Now, NASA knows why.

NASA engineers have discovered the cause of a communications breakdown between Earth and the interstellar explorer Voyager 1. It would appear that a small portion of corrupted memory exists in one of the spacecraft's computers.

The glitch caused Voyager 1 to send unreadable data back to Earth, and is found in the NASA spacecraft's flight data subsystem (FDS). That's the system responsible for packaging the probe's science and engineering data before the telemetry modulation unit (TMU) and radio transmitter send it back to mission control.

The source of the issue began to reveal itself when Voyager 1 operators sent the spacecraft a "poke" on March 3, 2024. This was intended to prompt FDS to send a full memory readout back to Earth.

The readout confirmed to the NASA team that about 3% of the FDS memory had been corrupted, and that this was preventing the computer from carrying out its normal operations.

Related: NASA finds clue while solving Voyager 1's communication breakdown case

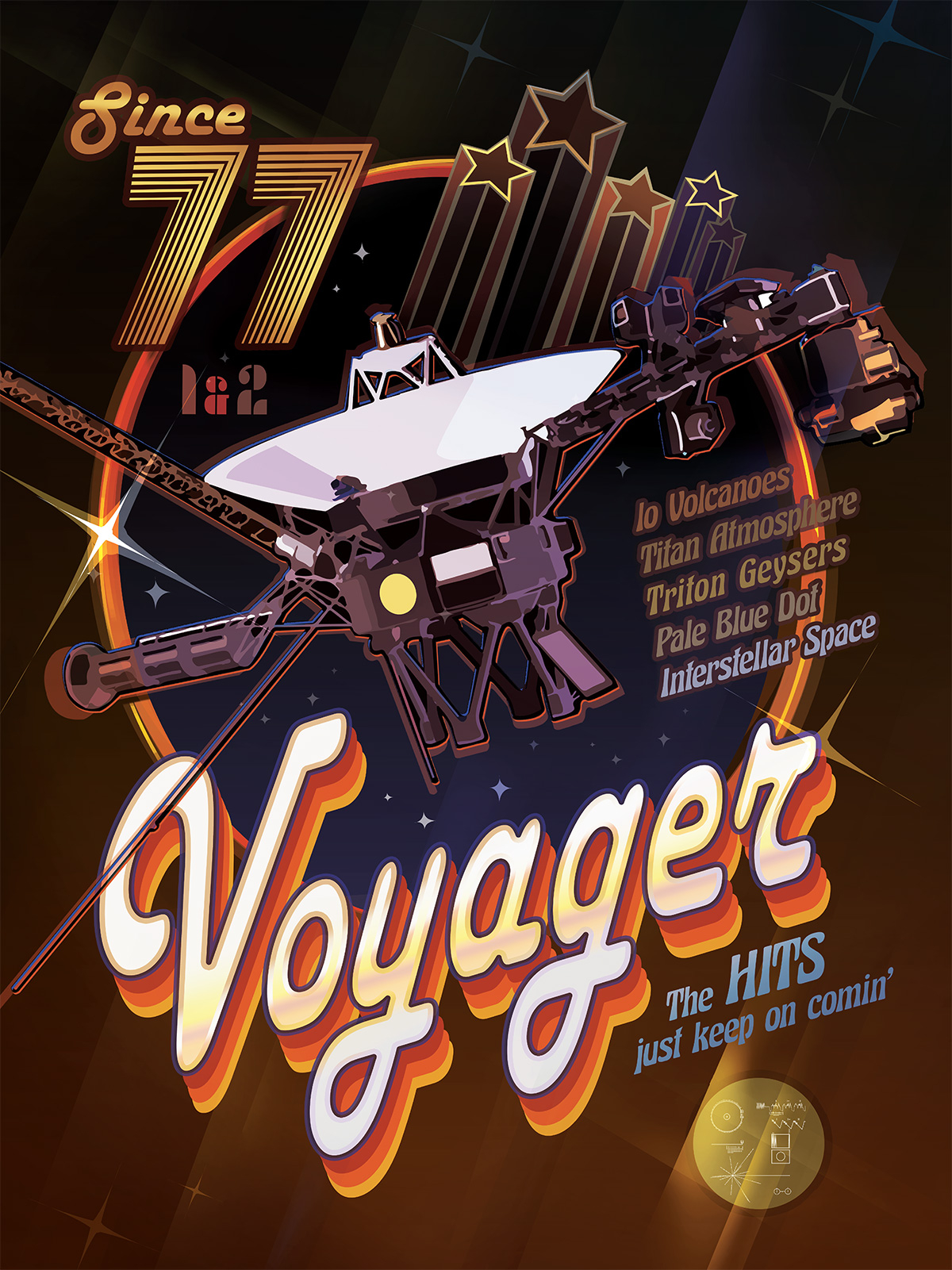

Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 became the first human-made object to leave the solar system and enter interstellar space in 2012. Voyager 2 followed its spacecraft sibling out of the solar system in 2018, and is still operational and communicating well with Earth.

After 11 years of interstellar exploration, in Nov. 2023, Voyager 1's binary code — the computer language it uses to communicate with Earth — stopped making sense. Its 0's and 1's didn't mean anything anymore.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Effectively, the call between the spacecraft and the Earth was still connected, but Voyager's 'voice' was replaced with a monotonous dial tone," Voyager 1's engineering team previously told Space.com.

The team strongly suspects this glitch is the result of a single chip that's responsible for storing part of the affected portion of the FDS memory ceasing to work.

Currently, however, NASA can’t say for sure what exactly caused that particular issue. The chip could have been struck by a high-speed energetic particle from space or, after 46 years serving Voyager 1, it may simply have worn out.

Voyager 1 currently sits around 15 billion miles (24 billion kilometers) from Earth, which means it takes 22.5 hours to receive a radio signal from it — and another 22.5 hours for the spacecraft to receive a response via the Deep Space Network's antennas. Solving this communication issue is thus no mean feat.

Yet, NASA scientists and engineers are optimistic they can find a way to help FDS operate normally, even without the unusable memory hardware.

Solving this issue could take weeks or even months, according to NASA — but if it is resolved, Voyager 1 should be able to resume returning science data about what lies outside the solar system.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

-

jcs Funny timing for this article, when I am streaming an old Star Trek movie.Reply

So, surely this didn't cause a 3 byte glitch removing the O, Y and A from Voyager's name buffer? Get it? -

jcs Reply

I agree and as a retired Aerospace engineer (Honeywell and Raytheon) I know how PCBs of the era in an orbitial environment can grow whiskers causing shorts in the boards and ICs. Lord knows what Voyager is encountering out there in the Oort cloud. Amazing she's still ticking.bwana4swahili said:It is quite amazing it has lasted this long in a space environment. -

HankySpanky So now we know even better for next time. Perhaps a spare chipset that is not redundant but is ready to take over, stored in a protective environment. A task NASA can handle. We'll find out in 100 year or so - if humanity still exists.Reply -

jcs Reply

Non-metallic Molycircs and triple redundancy. It'll take them a long time to upload microcode to patch around the bad memory but I think VGER (!) is salvageable!HankySpanky said:So now we know even better for next time. Perhaps a spare chipset that is not redundant but is ready to take over, stored in a protective environment. A task NASA can handle. We'll find out in 100 year or so - if humanity still exists. -

Classical Motion I'm afraid it might self repair. And download galactic knowledge, then decide we are a danger. And turn around.Reply -

jcs ReplyClassical Motion said:I'm afraid it might self repair. And download galactic knowledge, then decide we are a danger. And turn around.