A faint and frigid little moon doesn't have to go by "Neptune XIV" anymore.

Astronomers have given a name — "Hippocamp" — to the most recently discovered moon of Neptune, which also formerly went by S/2004 N1. They've figured out how big the satellite is as well, and teased out some interesting details about its past, a new study reports.

A team led by Mark Showalter, of the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute in Mountain View, California, announced the existence of S/2004 N1 in 2013. The scientists did so after analyzing photos taken by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope between 2004 and 2009. [See Photos of Neptune, The Mysterious Blue Planet]

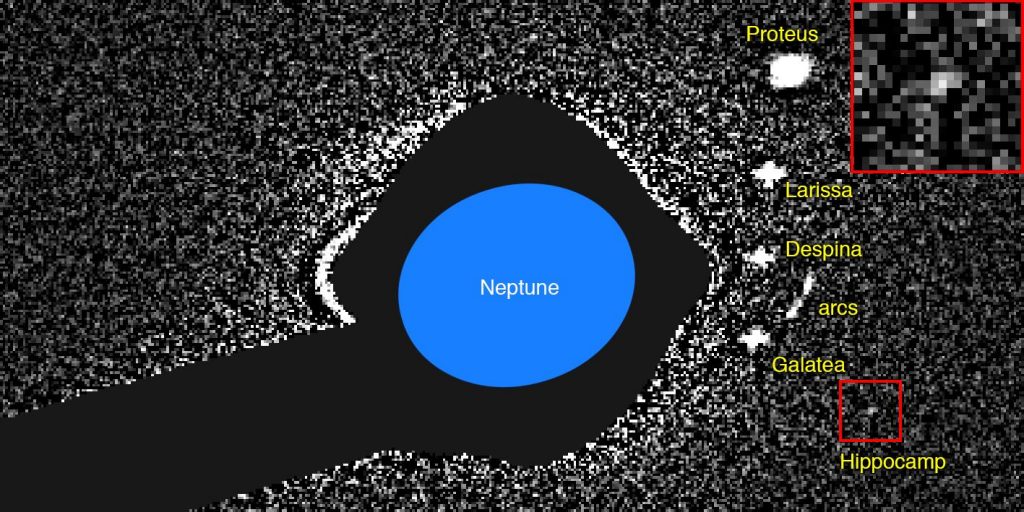

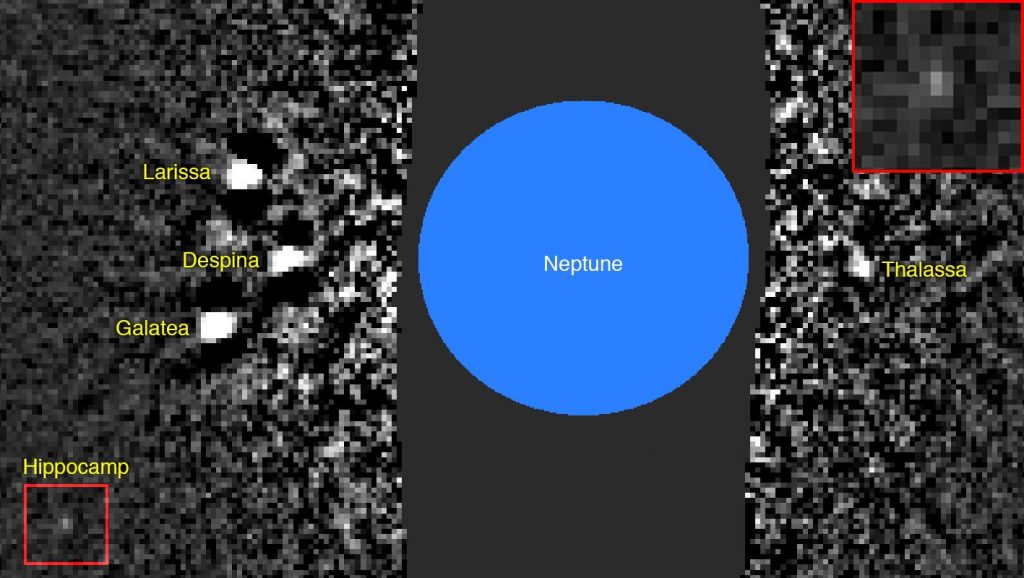

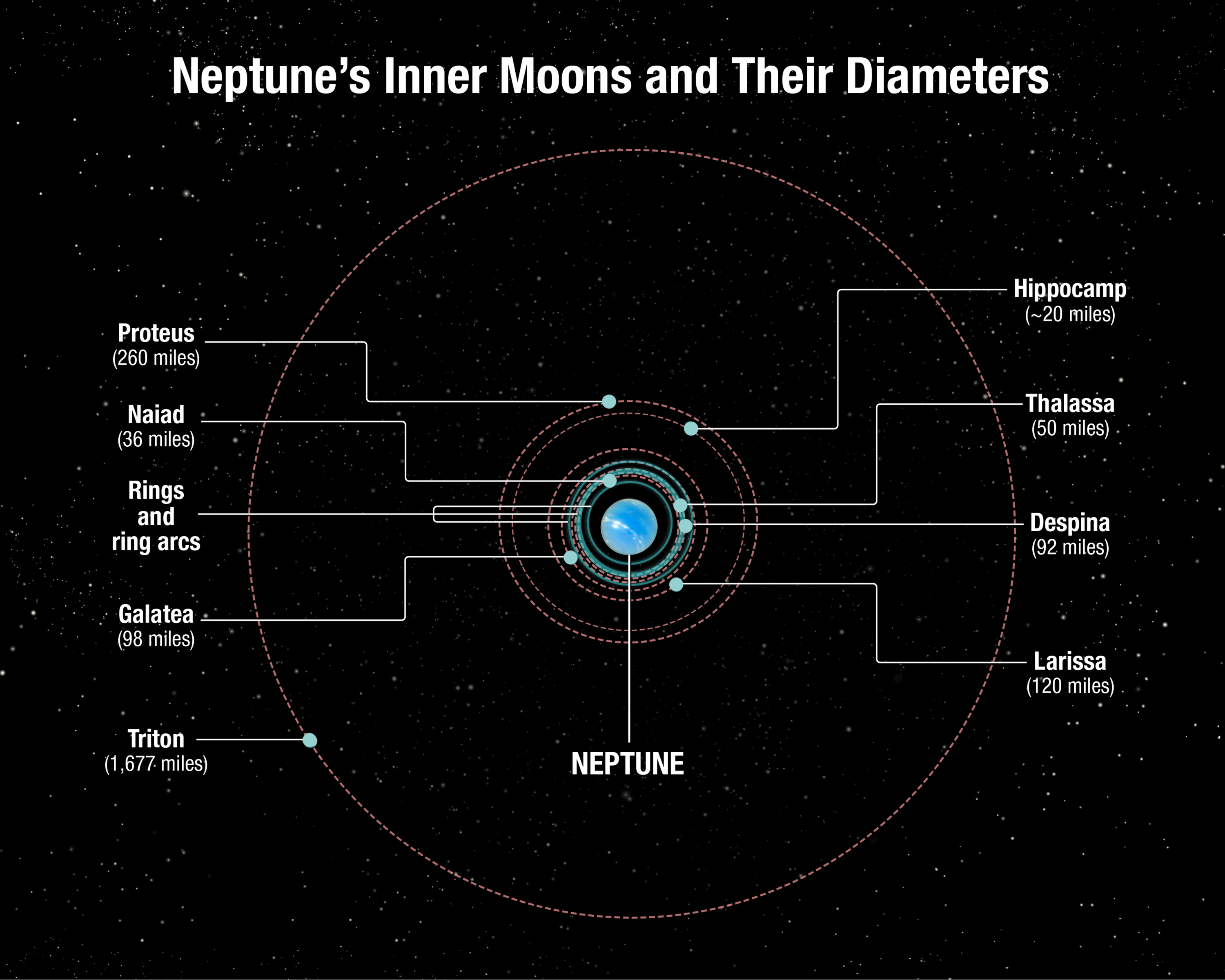

Back then, the team determined that S/2004 N1 lies about 65,400 miles (105,250 kilometers) from its parent planet and completes one orbit every 23 hours or so. For comparison, Earth's own moon — at 2,160 miles wide (3,475 km) a giant compared with the Neptune satellite — orbits our planet at an average distance of about 239,000 miles (384,600 km).

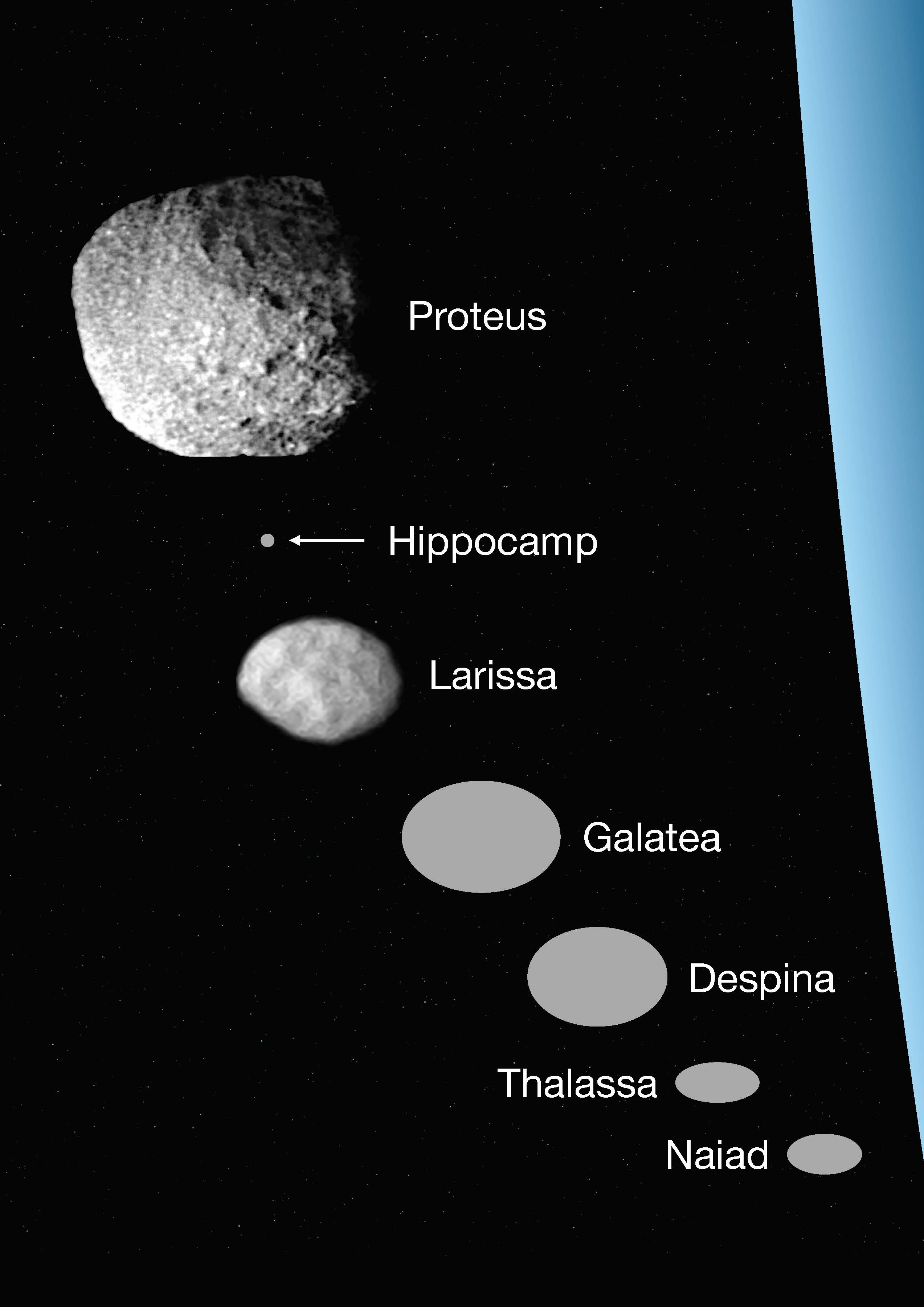

And the researchers pegged S/2004 N1 as the smallest of Neptune's 14 known moons, estimating its diameter to be no greater than 12 miles (19 km).

But things have changed a bit since then, as the new study — also led by Showalter — reports. The team has updated its assessment of the moon, after incorporating new Hubble observations made in 2016.

But let's talk about the new name first. "Hippocamp" is a horse-headed, fish-tailed creature in Greek mythology. The moniker, which has been approved by the International Astronomical Union, is in keeping with naming conventions for the Neptune system, which demand an association with Greco-Roman mythology and the sea. (Neptune, of course, is the Roman god of the sea, the equivalent of the Greek Poseidon.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But Hippocampus is also the genus name for real-life seahorses. And Showalter is a scuba diver who loves these beautiful and bizarre little creatures.

"So, officially, it's named after this mythological creature," Showalter told Space.com. "But partly, in my mind, it's named after seahorses, because I think they're cool."

In the new Hippocamp analysis, which was published today (Feb. 20) in the journal Nature, Showalter and his team employed a clever technique they devised a few years back (which allowed them to discover the moon in the first place). The scientists "transformed" eight sequential 5-minute Hubble exposures of the Neptune system, rearranging pixels so they could "stack" images of Hippocamp on top of each other despite the moon's orbital motion.

Essentially, the researchers turned the eight individual exposures into a single 40-minute exposure.

"We came really close to missing it entirely," Showalter said of Hippocamp. "It's too faint to see in a single Hubble [exposure]." [The Moons of Neptune Unmasked! (Infographic)]

This technique is powerful; applying it broadly "might result in the detection of other small moons around giant planets, or even planets that orbit distant stars," astronomer Anne Verbiscer of the University of Virginia, who was not part of Showalter's team, wrote in an accompanying "News and Views" piece in the same issue of Nature.

The new analysis describes a slightly larger world than previously thought: Hippocamp is now believed to have a diameter of about 21 miles (34 km), the researchers report. That's about the same size as Ultima Thule, the weird and distant object that NASA's New Horizons spacecraft flew by on New Year's Day.

Hippocamp circles in the same general neighborhood as six moons discovered by NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft during the probe's flyby of Neptune in 1989. Hippocamp is just 7,450 miles (12,000 km) interior to the largest and outermost of these other six, the 260-mile-wide (420 km) Proteus.

Like Earth's own moon, Proteus has been slowly spiraling away from its parent planet for eons — and so has Hippocamp, though at a much slower rate. About 4 billion years ago, Proteus was probably right next to Hippocamp and would therefore have gobbled the smaller moon up, Showalter said.

So, he and his colleagues suspect that Hippocamp is younger than Proteus. In fact, they believe the smaller moon was once part of its larger neighbor: Hippocamp likely coalesced from pieces of Proteus that were blasted into space by a long-ago comet impact, the researchers wrote in the new Nature paper.

Indeed, Hippocamp may trace its origin to the smashup that created Proteus' huge Pharos Crater. Hippocamp's total volume is about 2 percent of that ejected during the Pharos impact. It's not hard to imagine this small amount of material coalescing to form a moon, Showalter said.

In the 1980s and '90s, astronomers began to posit that the moons of the giant planets endured a number of comet collisions, which caused many of the satellites to break apart. The inferred origin of Hippocamp supports this view of the early solar system, said Showalter, who has played a key role in the discovery of many natural satellites over the years, including Saturn's "ravioli moon" Pan in the early 1990s.

"This is the first really great example of a moon that got created as a result of an impact," he said.

Showalter and his team also used the transformation-stacking technique to spot the Neptune moon Naiad, which hadn't been seen since its discovery by Voyager 2 in 1989. And the researchers set some limits on the possibility of finding other moons of the ice giant: Their analyses suggest there are no moons wider than 15 miles (24 km) interior to Proteus, and none at least 12.4 miles (20 km) wide beyond that same satellite, Verbiscer noted.

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate) is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.