December's new moon allows the Geminid meteor shower to shine tonight

An almost-moonless night means seeing the meteor shower will be easier; a bright moon tends to drown them out.

The new moon of December 2023 offers skywatchers dark skies for catching one of the year's best meteor showers.

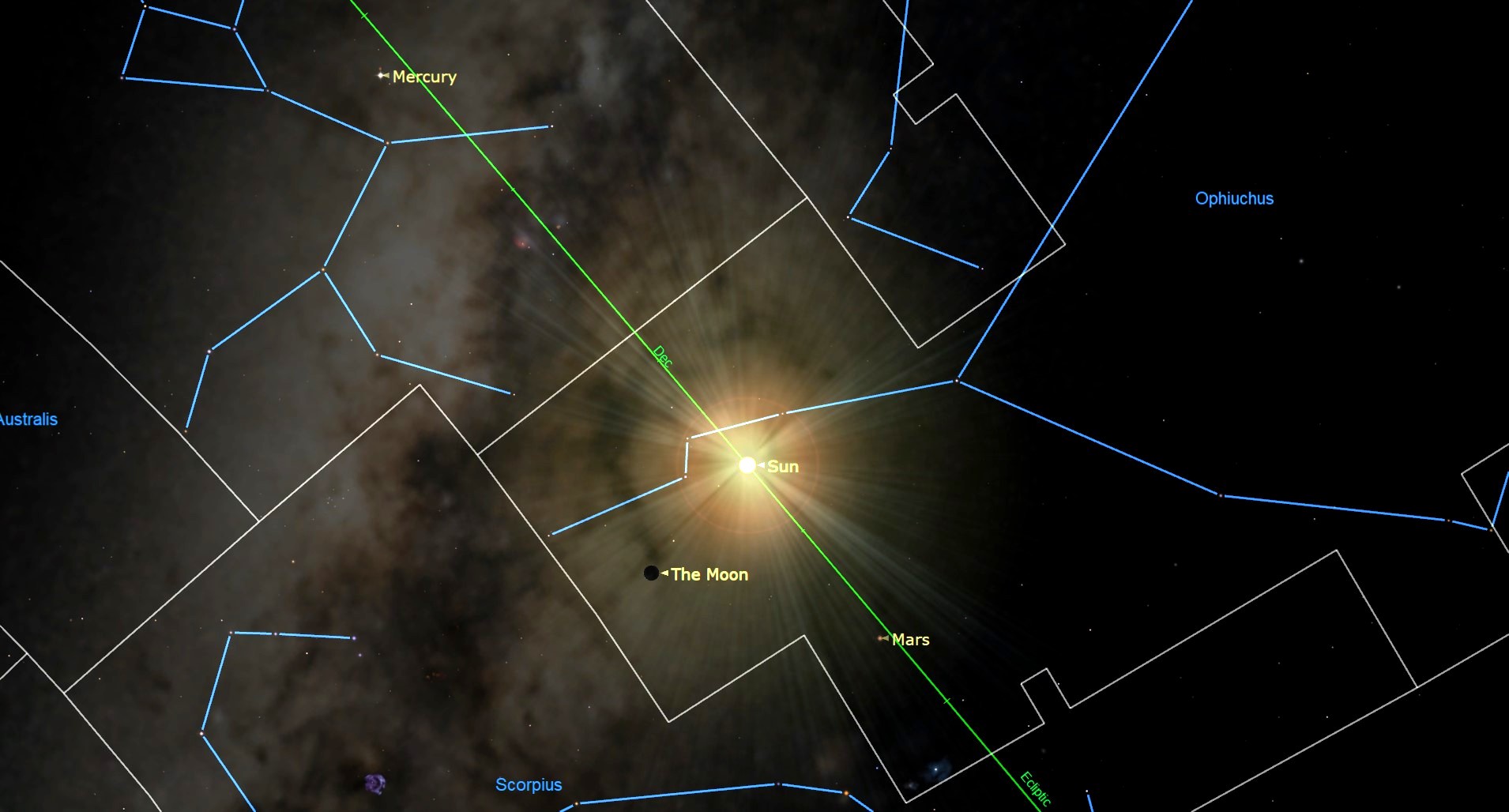

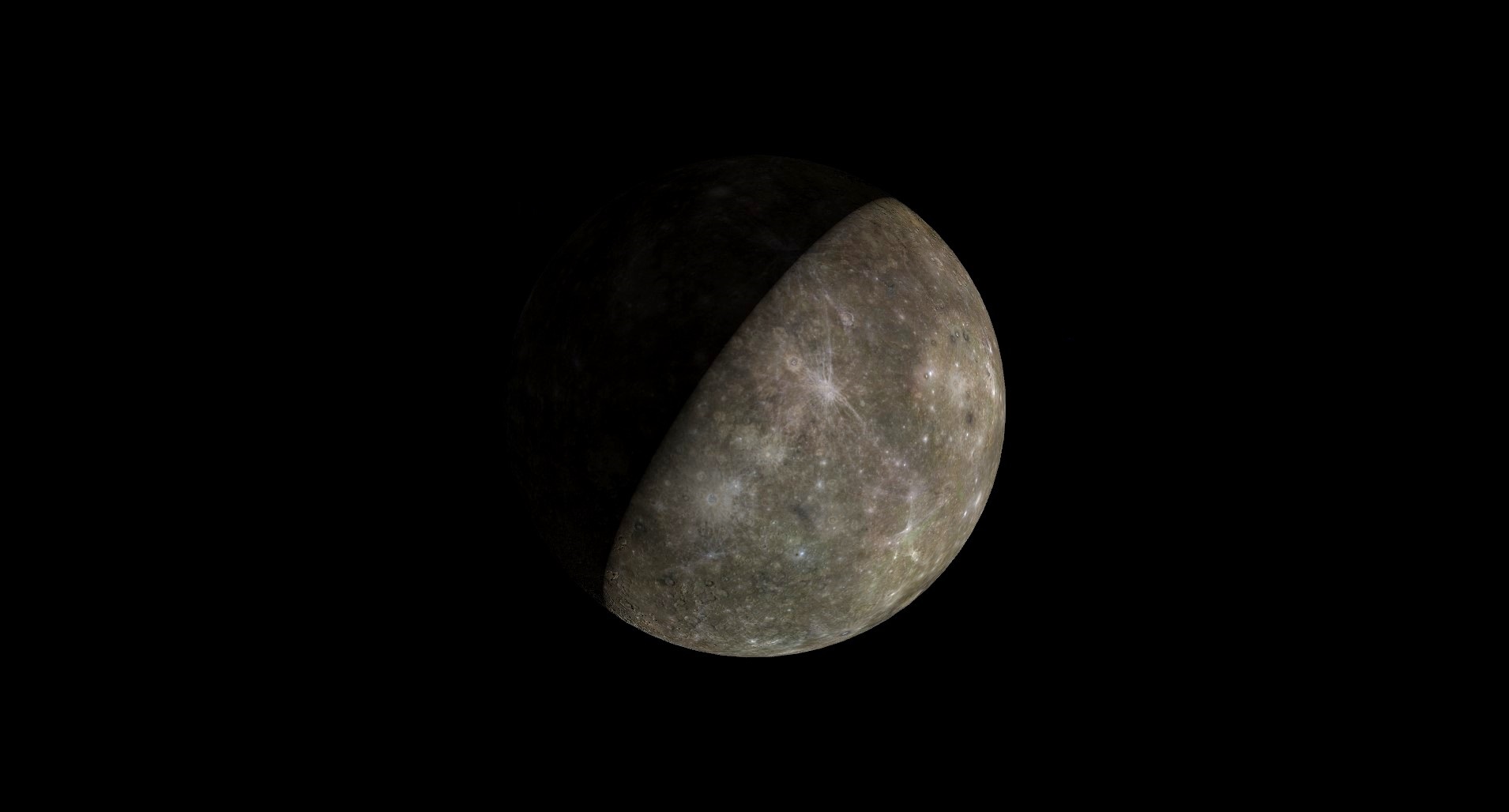

The new moon of December occurs on Dec. 12, 6:32 p.m. Eastern (2332 UT), according to the U.S. Naval Observatory. The young crescent moon will share the sky with the Geminid meteor shower, which is one of the most abundant meteor showers of the year, and two days later the moon will make a close pass to Mercury, making the elusive innermost planet easier to spot.

New moons happen when the moon passes between Earth and the sun, specifically when the sun and moon shares the same celestial longitude as our parent star. A line from north to south from the celestial pole would pass through both. The moon isn't visible unless there is a solar eclipse, and that means the nights are particularly dark; when meteor showers occur on or near new moons it's a lot easier to see them as the moon's light isn't washing them out.

Related: Geminid meteor shower 2023: When, where & how to see it

Geminid meteors

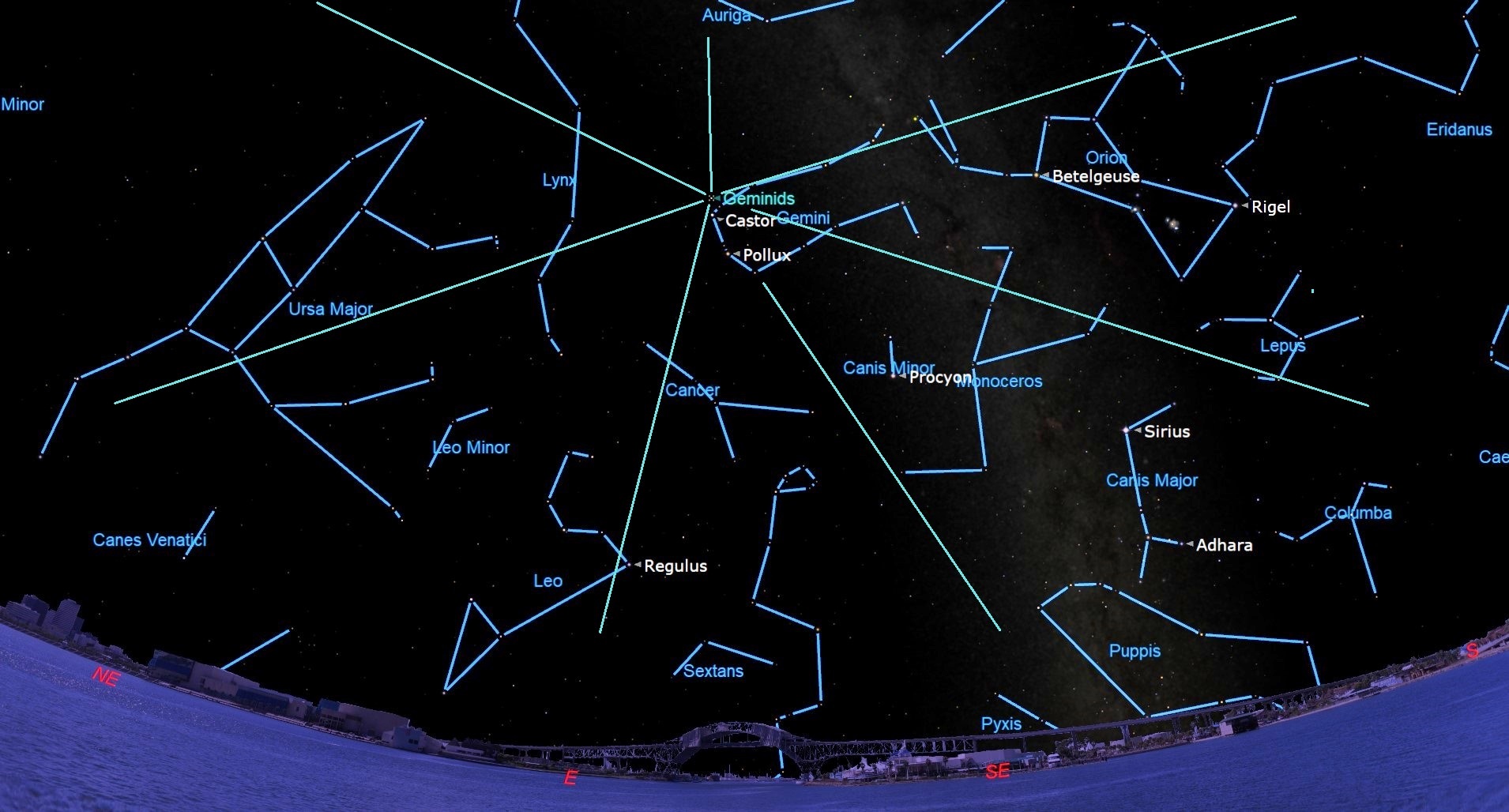

The Geminid meteor shower peaks on Dec. 14, just two days after the new moon, and the waxing crescent moon will set in New York by about 6:00 p.m. An almost-moonless night means seeing the meteor shower will be easier; a bright moon tends to drown them out.

The Geminids can produce as many as 150 meteors per hour, according to the American Meteor Society – they are in many respects a winter version of the more famous Perseids. The radiant point (where the meteors seem to come from in the sky) is as the name implies in the constellation Gemini, which in mid-northern latitudes clears the horizon by about 8 p.m. and so is above the horizon almost all night. No moon in the sky means that with clear skies one might see a robust meteor shower, including fainter meteors that otherwise would be impossible to see (provided one is away from city lights).

A young moon passes Mercury

Look at awesome stuff in the night sky up close! We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

On the same day that the Geminids reach peak activity, our satellite makes a close pass to the planet Mercury, reaching conjunction at 12:20 a.m. EDT on Dec. 14 (0520 GMT). The moon will pass about 4 and one-third degrees south of Mercury; that's just under nine lunar diameters.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For North American observers the moon and Mercury won't be visible at that point, but in New York they will both be above the horizon by 8:30 a.m. EDT and become just visible as the sky darkens – sunset is at 4:29 p.m., and the sky will start to get dark by 5:00 p.m. (nautical twilight, when the sun is between 6 and 12 degrees below the horizon, ends at 5:34 p.m.)

While it is possible to spot the thin crescent moon as the sun sets, Mercury, which will appear to the right of the moon and slightly below it, will set at 5:34 p.m. and so will be a difficult target, as by 5 p.m. it is less than 5 degrees high in the southwest. (While it is possible to try and observe Mercury and the moon during the day, they are close enough to the sun that one must be extremely careful; looking at the sun with even small optical aids can cause permanent eye damage up to and including blindness).

Observing the two is more easily done if one goes southwards; as one gets closer to the equator the moon and Mercury both approach the horizon at a steeper angle. From Miami, Florida, Mercury sets at 6;38 p.m. Eastern and the moon at 7:08 p.m., while sunset is at 5:31 p.m. By 6:00 p.m. Mercury is just under 7 degrees above the southwestern horizon; if there are no obstructions it is just bright enough to be visible. To find it one must look for the moon, which will be almost due southwest, and then look to the right (more westwards) and downwards, towards the horizon. With an obstruction-free view (looking out over flat fields, lakes, or the ocean) one should be able to catch the innermost planet just before it sets.

In San Juan, Puerto Rico, the moment of conjunction is at 1:20 a.m. Dec. 14. Mercury sets at 6:56 p.m. local time on that day, while the sun sets at 5:47 p.m. By 6:30 p.m. Mercury is 5 degrees above the horizon in the southwest. Here too the moon will appear to be above Mercury, with Mercury to the right and closer to the horizon.

To be closer to the moment of conjunction in the evening or at night (it can't happen in the morning because the sun rises before the pair) one has to go to westwards; in Honolulu, Hawaii, the conjunction happens on Dec. 13 at 7:20 p.m. local time and sunset is at 5:51 p.m. Being closer to conjunction means that the moon – which moves eastwards against the background stars – is closer to Mercury, and because Hawaii-based observers are seeing it slightly before conjunction, the moon is a bit east of the planet. That means instead of being to the left of Mercury, the moon is somewhat to the right and below it; unlike the situation on the East Coast of the U.S. the moon sets first, at 6:42 p.m. By 6:15 p.m. Mercury will be 8 degrees high in the west, when civil twilight ends, and the planet sets at 7:01 p.m. All this means that when you spot the moon in Hawaii, to catch Mercury one must look up from the moon and to the right.

Better views of Mercury are from southeastern Asia; in Manila, sunset is at TKT, the moon sets at 5:35 p.m. local time, and Mercury is still 8 and a half degrees above the western horizon at 6 p.m. gets higher in the sky;

In the Southern Hemisphere, spotting Mercury will be as challenging as doing so in the Northern Hemisphere, though the moon and the planet will set later as it is the austral summer. In Melbourne, Australia, the conjunction happens at 4:20 p.m. local time on Dec. 13, but the sun doesn't set until 8:36 p.m. The moon will set very soon after that, at 9:15 p.m. and will be less than a day old – the New moon is at 10:32 a.m. local time that same day, so it will be nearly invisible (it's a very thin crescent nearly lost in the solar glare). By 9 p.m. local time Mercury is just under 9 degrees high in the west; as the sky darkens it should start to emerge. The planet sets at 9:54 p.m. local time.

Other visible planets

Mercury isn't the only planet visible the night of the new moon. Once the sky is dark in the evening, mid-northern latitude observers will see Saturn just west of due south by about 6 p.m. Saturn is in the constellation Aquarius, so it stands out as Aquarius is a fainter constellation. Jupiter, meanwhile, will be in the southeast, about 44 degrees high at the latitude of New York City, and as it is also in a fainter constellation – Aries – it will be distinct against the background stars.

For Southern Hemisphere observers Saturn will appear more westerly as the sun sets (since it is later in the evening when it gets dark) – in Sao Paulo, Brazil, for example, where the sun doesn't set until 6:47 pm. on Dec. 12, and by 8:30 p.m. local time Saturn is 38 degrees above the western horizon, as the planet sets there at 11:24 p.m. Jupiter at that point is almost due north and a full 53 degrees high.

Venus will be a bright "morning star" – the third-brightest object in the sky (after the sun and moon) it can be seen even as the sky gets light towards sunrise. In New York Venus rises at 3:42 a.m. and sunrise is at 7:10 a.m.; by 6:30 a.m. the sky will be just getting light and Venus will still be visible in the southeast about 30 degrees high.

In the Southern Hemisphere the planet will appear further northwards; in Sao Paulo, Brazil, sunrise on Dec. 12 is at 5:13 a.m. local time, and Venus rises at 2:48 a.m. By 4:30 a.m. the Venus will appear almost due east and 24 degrees high.

Stars and constellations

December is winter in the Northern Hemisphere, and with that we see the winter constellations in full swing. By 6 p.m. in much of North America, Europe and Asia the sun has fully set and the sky is dark, allowing for more time to observe during the night. The colder air also means the nights tend to be clearer.

In the east by 8 p.m. Gemini, Taurus and Orion are all above the horizon, with the distinctive belt of the latter pointing nearly straight up – Orion's belt runs roughly east-west, but at a slight angle that makes it look vertical at certain times of night in mid-northern latitudes. Taurus the Bull can be found by looking for Orion, and using the Belt stars, look upwards and to the left (towards the north) to spot Betelgeuse, which would be Orion's left shoulder (from the point of view of the ground); Betelgeuse is distinct because of its reddish hue. Look just eastwards (to the right) and one spots Bellatrix, Orion's other shoulder (Harry Potter fans should know that yes, this is where the name of a prominent antagonist in the series comes from).

If one looks northward (upwards as Orion gets higher above the horizon) one will spot the open star cluster the Hyades, which marks the "head" of Taurus the Bull. The brightest star in the constellation is Aldebaran, also distinctive because of its orange color.

On the other side of Orion is Gemini – to find it draw a rough line between the rightmost star of Orion's Belt, called Mintaka, and Betelgeuse. Continue that line and one and it will pass just above two bright stars near each other, these are Castor and Pollux, which mark the heads of the eponymous Twins of Gemini.

Turning further north, Auriga the Charioteer is about a third of the way up the sky, and if one has a clear view northward, the Big Dipper seems to be horizontal, near the horizon, pointing up towards Polaris, the Pole Star. Meanwhile, Cassiopeia the queen is almost exactly as far from the pole as the Big Dipper and on the opposite side, forming an inverted "W" shape. By 9 p.m. both constellations have visibly moved, with the Big Dipper becoming more vertical – it will be in the lower right quadrant of the sky as one faces Polaris, with the "bowl" facing left, and Cassiopeia to the left (or west) of Polaris.

By 10 p.m. local time Canis Major, the Big Dog, is fully above the horizon, containing Sirius, the brightest star in the sky; it will be in the southeast. Canis Minor, the Little Dog, is to the left (northwards) and one can see Procyon, its brightest star, which makes a rough triangle with Sirius and Betelgeuse.

From the mid-southern latitudes, the sky doesn't get fully dark until about 9 p.m. Southern Hemisphere observers will see Sirius towards the east, with Orion in an "upside down" orientation to the left (northward).

Turning southeast (to the right) one will see Canopus, the brightest star in the constellation Carina, the Keel of the Ship. Most often associated with the legendary Argo that carried Jason and his crew. Sirius, Rigel, and Canopus form a triangle – it looks a bit like a right-angle triangle with the 90-degree angle at Sirius. One can use that to spot Achernar, the end of Eridanus the River, by drawing a line that goes from Sirius directly between Canopus and Rigel (imagine drawing a line from the 90-degree corner of a right triangle that bisects the hypotenuse). Achernar is quite high in the sky – 67 degrees, about two thirds of the way to the zenith at the latitude of Cape Town, Buenos Aires or Melbourne. Achernar is one end of the river, and one can trace it all the way back to a star near Rigel that marks the other end.

If you want to try your hand at photographing the Geminids during the young moon this month, be sure to check out our how to photograph meteors and meteor showers guide. And if you need imaging gear, consider our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Editor's note: If you snap a great photo of the Geminid meteor shower that you'd like to share with Space.com and our news partners for a story or image gallery, send images and comments to spacephotos@space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.