Spot dwarf planet Ceres during the new moon tonight

Ceres reaches opposition on March 21, and observers have a dark sky in which to view the dwarf planet.

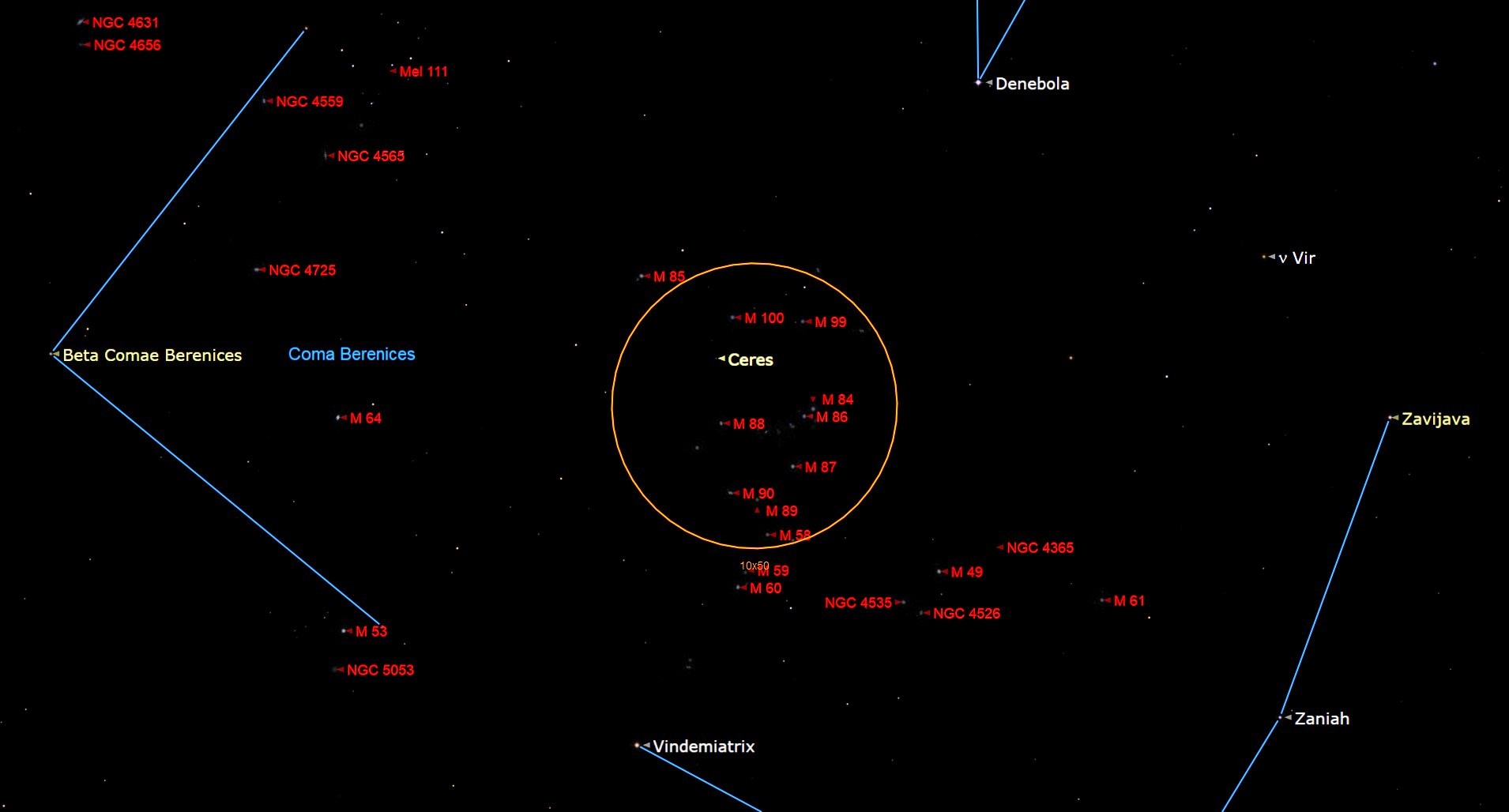

As the moon reaches its new phase on Tuesday (March 21), the dwarf planet Ceres will lie opposite the sun in Earth's sky, in an arrangement astronomers call "opposition."

Ceres will be visible for most of the night with no moonlight to drown it out, but don't expect mind-bending views: The dwarf planet will be a star-like point of light, even through a telescope, according to In the Sky.

Located in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, the dwarf planet officially known as 1 Ceres will be in the constellation of Coma Berenices. While in opposition, Ceres will also be in perigee — its closest approach to Earth during its orbit around the sun — meaning the dwarf planet will be at its brightest.

Related: March 2023 skywatching guide

Looking for a telescope to observe the moon, Ceres or anything else in the sky? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

From New York City, In the Sky added, Ceres will become observable from around 8:35 p.m. EDT (0035 GMT on March 22) when it will rise to 21 degrees over the horizon to the east. Ceres will reach its highest altitude at around 1:31 a.m. EDT (0531 GMT) on March 22, when it will be 64 degrees over the horizon to the south. Ceres will disappear when the sun's light washes it out at around 5:51 a.m. EDT (0951 GMT) as it sits at around 28 degrees over the horizon to the west. (For perspective, your clenched fist held at arm's length spans about 10 degrees of sky.)

During the close approach, Ceres will still be around 147 million miles (237 million kilometers) from Earth. It will reach a peak brightness magnitude of around 6.9, meaning that, even through a telescope, it will appear as no more than a point of light.

Ceres is the largest object in the main asteroid belt and has the distinction of being the only dwarf planet in the inner solar system. Most of these objects are located in the Kuiper Belt, a band of icy bodies out beyond the orbit of Neptune.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Spotted in 1801 by Giuseppe Piazzi, Ceres was initially believed to be an asteroid but was eventually found to be much larger than other bodies in the asteroid belt, receiving its dwarf planet designation in 2006.

Though Ceres comprises a quarter of the mass of the entire asteroid belt, the solar system's most famous dwarf planet Pluto is still 14 times more massive than Ceres, which is just 592 miles (953 km) wide. If Earth were the size of a nickel, NASA said, Ceres would be no larger than a poppy seed.

In 2015, Ceres, which takes 4.6 Earth years to orbit the sun, became the first dwarf planet to be visited by a spacecraft. NASA's Dawn mission studied Ceres from orbit from 2015 to 2018, after circling another of the asteroid belt's largest objects, Vesta.

Though Ceres lacks an atmosphere and a magnetosphere, planetary scientists are keen to explore it, as it may be composed of around 25% water, a key ingredient for life.

If you're hoping to catch a look at the new moon or Ceres during the dwarf planet's opposition and close approach, our guides to the best telescopes and best binoculars are a great place to start. If you're looking to snap photos of the night sky in general, check out our guide on how to photograph the moon, as well as our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Editor's Note: If you snap Ceres or the new moon and would like to share it with Space.com's readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.