September's new moon points the way to Mars, Jupiter and more

An observer's guide to the new moon of September 2023.

The new moon occurs tonight (Sept. 14) at 9:40 p.m. EDT (0140 UTC on Sept 15), per the U.S. Naval Observatory.

Earth's natural satellite just swung by Mercury on Wednesday (Sept. 13), and it will have an encounter with Mars two days from now.

New moons occur when the moon is between the sun and Earth, which happens about every 29.5 days. Indeed, the word "month" is derived from "moon," and the length of a lunar cycle is why many calendars, including the one we use today, have 30-day months.

Related: New moon calendar 2023: When is the next new moon?

Technically, the moon and Earth share the same celestial longitude, an alignment called a conjunction. Celestial longitude is a projection of Earth's own longitude lines on the sky; during new moons, if you drew a line from the pole star due south through the sun, it would hit the moon. Since the illuminated side of the moon faces away from Earth, new moons are invisible to ground-based observers, unless the moon passes directly in front of the sun, which creates a solar eclipse.

That won't happen this month — the next solar eclipse is due on Oct. 14 of this year and will be visible in the western U.S., Mexico, Central America and northern South America. The reason eclipses don't happen every month is that the moon's orbit is inclined to the plane of Earth's orbit by about 5 degrees, so the moon doesn't line up perfectly with the sun each cycle.

The timing of lunar phases is determined by time zone (or longitude), because it is measured on the moon's position relative to Earth rather than your position on Earth's surface. Therefore, the time of the new moon is 6:40 p.m. in Los Angeles, 2:40 a.m. in Paris, and 10:40 a.m. in Tokyo.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

On Wednesday, the moon passed near the planet Mercury in the predawn sky; the moon was in conjunction with the solar system's innermost planet and was about 6 degrees north of it. (Your clenched fist held at arm's length covers about 10 degrees of sky.) However, the pair were very close to the horizon, and the actual moment of conjunction wasn't visible from the U.S.; it happened at 1:41 p.m. local time, and the very thin crescent moon was too close to the sun to observe easily (or safely — you should be very careful when making any observations near the sun when it is above the horizon. Any optical aid such as binoculars can cause retinal burns and permanent damage to your vision).

After the new moon, on Saturday (Sept. 16), at 3:20 p.m. EDT, New York City observers will see the moon make a close pass to Mars, passing within 39 arcminutes of the planet. That's just over half a degree, or one lunar diameter. As with the Mercury conjunction, it will be during the day, so the pair won't be readily visible until the evening. Even though the moment of conjunction will have passed, the sun sets at 7:03 p.m., and at that point the moon will be a thin crescent about 8 degrees above the western horizon. Mars will be just slightly below and to the right of the moon, at just under 8 degrees high. The moon and Mars still won't be easy to spot unless you have a clear western horizon free of any buildings or tall trees. Both set by about 7:49 p.m. local time.

Related: September full moon 2023 guide: The Super Harvest Moon joins Jupiter and Saturn

Farther south, the moon and Mars will be easier to see. In Miami, the sun sets at 7:24 p.m. EDT on Sept. 16 and the moon and Mars will be 11 degrees above the western horizon at the time, so there will be more time to pick them out against the darkening sky. Both objects set at about 8:20 p.m.

In the Southern Hemisphere, the positions of the moon and Mars appear "switched" — the day-old moon will be just to the right of Mars, as opposed to the left. In Buenos Aires, the sun sets on Sept. 16 at 6:46 p.m. Argentine Standard Time, and the moon will be about 6.5 degrees above the western horizon. The pair sets at about 8:15 p.m. local time, and the sky should be dark enough that with a flat horizon and clear conditions you can see the two.

Visible planets

Looking for a telescope to see visible planets in the night sky? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

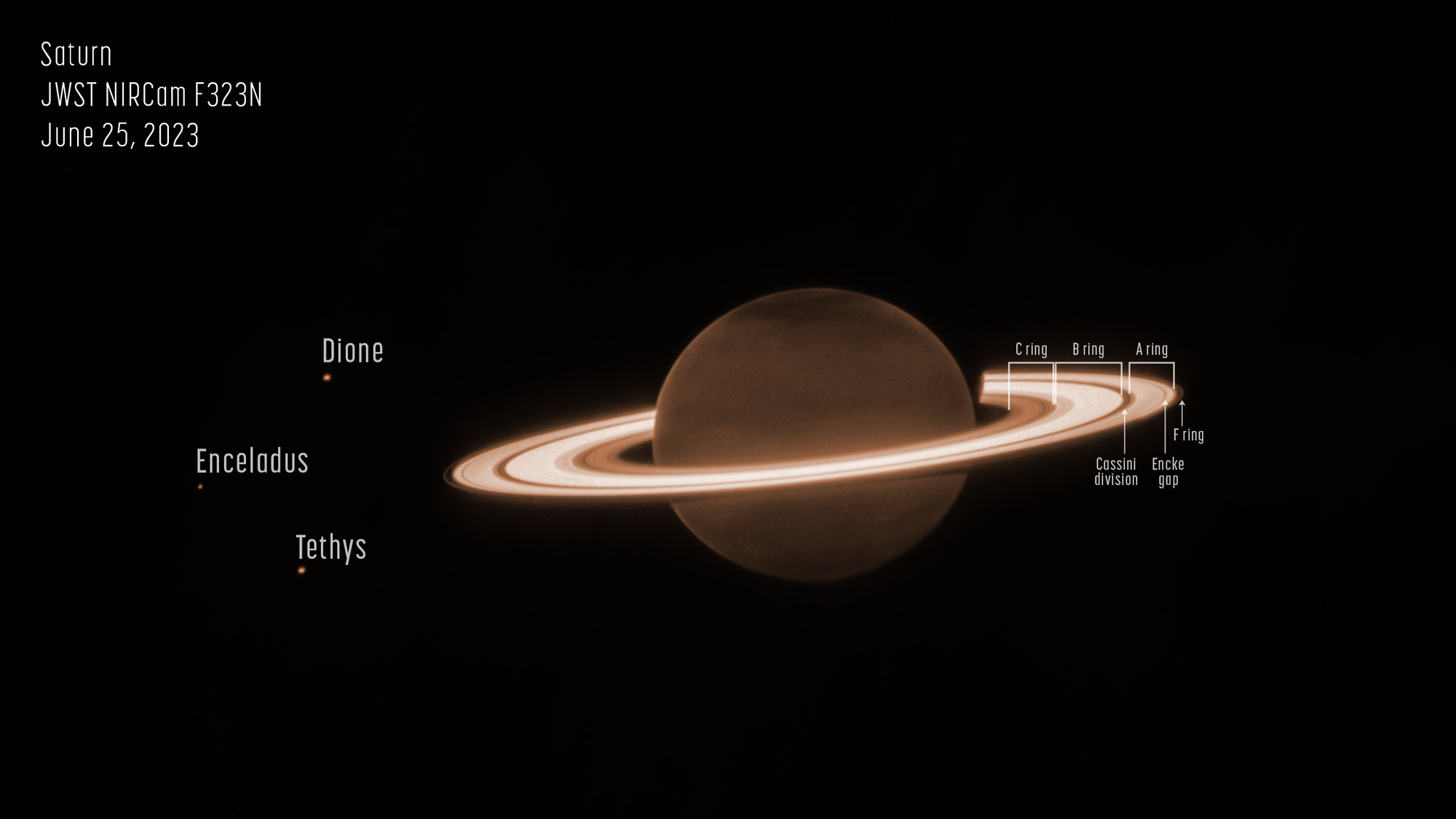

Besides the conjunctions, other planets will grace the skies on the night of the new moon itself. While Mercury and Mars will both be lost in the solar glare, Saturn will be visible effectively for the entire night of Sept. 14-15, as the planet rises at 6:22 p.m. EDT at the latitude of New York City, 45 minutes before sunset. (Times are from calculations by the U.S. Naval Observatory.) The ringed planet is in the constellation Aquarius, a relatively faint group of stars, so it will stand out as the sky darkens.

Saturn will reach its maximum altitude at about 11:45 p.m., when it is some 37 degrees above the southern horizon, and will set at 5:08 a.m. local time in the southwest. Southern Hemisphere observers will see the planet much higher in the sky; in Cape Town, Saturn rises at 4:57 p.m. local time, while the sun sets at 6:37 p.m. The planet will reach peak altitude at 11:32 p.m. local time, getting a full 68 degrees above the northern horizon.

The next planet you will see is Jupiter, which in New York rises at 9:17 p.m. local time. Jupiter will get higher in the sky than Saturn; in New York, it will hit an altitude of 64 degrees at 4:13 a.m. on Sept. 15 as you look due south. From Cape Town, Jupiter will be lower in the sky, hitting 41 degrees above the northern horizon at 4:04 a.m.

Venus will be a morning star, rising at 3:48 a.m. in New York on Sept. 15. Venus is the third-brightest object in the sky after the sun and moon, so it is easily recognizable. By sunrise (which is at 6:36 a.m.) the planet will be 32 degrees above the eastern horizon; it is often one of the last celestial objects visible as day breaks. In the Southern Hemisphere, the planet rises towards the northeast; in Cape Town it will rise at 4:40 a.m., and sunrise is at 6:46 a.m. local time. Venus is in the constellation Cancer. Cancer is a faint grouping of stars that is difficult to see from urban areas, so Venus will stand out.

Related: Night sky, September 2023: What you can see tonight [maps]

Constellations

In mid September, by about 9 p.m., the Summer Triangle — an asterism made up of the stars Deneb, Altair and Vega — is almost directly overhead in northern mid-latitudes. It's recognizable, as the three stars are bright enough to see even in a city location. Altair, the "eye" of Aquila, the Eagle, is the southernmost part of the triangle; you can imagine it as the "bottom" tip of a triangle pointing south. (It is also quite high in the sky in the contiguous United States; in Bellingham, Washington, it is about 50 degrees high at 9 p.m. local time, whereas in Miami it is about 70 degrees above the horizon).

From Altair, you can look straight up and see Deneb on the left and Vega on the right to complete the Triangle. Deneb is the tail of the constellation Cygnus, the Swan, and Vega is the brightest star in Lyra, the Lyre. Cygnus forms a cross shape and it is sometimes called the Northern Cross; if you follow the long axis of the cross roughly toward Altair, you reach the star Sadr, the center of the cross, and then Albireo, the "head" of the Swan.

Drawing a line between Vega and Deneb and extending it toward the northeastern horizon, you end up between Cassiopeia and Pegasus. Cassiopeia is easier to recognize; it is a compact "W" shape centered about 30 degrees up and facing left (north), so it looks like the number 3. To the right of Cassiopeia is a large square of stars with one corner toward the horizon; this is the Great Square.

The Great Square is an asterism that is made up of two constellations, Pegasus and Andromeda. Andromeda starts at the left corner; it's two lines of stars that extend to the left (roughly northward). From Andromeda's head, you can trace two lines of stars and find the Andromeda galaxy, which can be spotted from a dark-sky site with the naked eye. The other three stars form the wing of Pegasus, the legendary winged horse of Perseus, the hero, who can be seen just clearing the horizon below Cassiopeia.

In the western half of the sky, you can see Sagittarius; it will be close to the horizon in the south. Scorpius will be mostly set, though the heart of the Scorpion, Antares, is still just high enough to see if the horizon is clear of obstructions; it is only about 10 degrees high. Above Scorpius, you can see Ophiuchus, the Serpent Bearer. To find it, look for Antares, and then go upward from the horizon; you should see a large rectangle of fainter stars with the short side horizontal. That's the body of Ophiuchus, and above the rectangle is a star that makes an "A frame" shape, which is his head. Ophiuchus is sometimes called the 13th constellation of the Zodiac, because the constellation's modern borderlines mean that planets often pass through it.

For those in the Southern Hemisphere, some planets that are low in the sky in mid-northern latitudes are much higher. On the night of Sept. 17, for example, the new moon occurs at 10 p.m. Australian Eastern Standard Time. At that point, Mars will be about 15 degrees above the horizon, Jupiter 58 degrees above the horizon and Saturn 63 degrees up. Jupiter sets at 3:06 a.m. local time, whereas Saturn sets 29 minutes later.

Constellations visible in the Southern Hemisphere on Sept. 14 at about 9 p.m. local time will include the Southern Cross, Centaurus the Centaur and the Southern Fish. From mid-southern latitudes such as Cape Town or Santiago, Chile, or Melbourne, Australia, The Southern Cross (officially called Crux) is in the southwest, about 26 degrees above the horizon. It's a compact group, and the "bottom" of the cross, marked by Acrux, faces toward the Southern Celestial Pole. Above the Cross are two bright stars; the first one (as you move upward) is Hadar, and the second is Rigil Kentaurus, otherwise known as Alpha Centauri. These are sometimes taken to be the front hooves or legs of the Centaur.

Turning toward the southeast (to the left), you will see a bright star that at 9 p.m. local time will be a bit below the altitude of the Cross. (Imagine drawing a straight horizontal line almost halfway across the sky.) This is Achernar, the end of Eridanus, the River. The River extends below the horizon — the rest of it doesn't rise until later — but the other end is near the foot of Orion. If you continue turning left (toward the east) you encounter Fomalhaut, the brightest star in Piscis Austrinus, the Southern Fish.

Turning northward, you can see the Summer Triangle, but from below the equator it is "upside down," with Vega closer to the horizon, about 15 to 20 degrees high depending on your latitude, with Altair above and to the right. Deneb is hard to see from the southern latitudes; it will be to the right of Vega but only a few degrees above the horizon. In the high western sky, you can spot an upside down Scorpius, which in the southern skies faces toward the horizon and is much higher, with Antares about 56 degrees high if you're at the latitude of Santiago, Chile.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.

-

Jan Steinman "during new moons, if you drew a line from the pole star due south through the sun, it would hit the moon."Reply

I'm having trouble visualizing this.

Polaris is some 350 light years from us. Wouldn't any line drawn from Polaris through the Sun enter the Sun at nearly it's north pole, not even approaching the orbit of the Earth?