No asteroid impacts needed: Newborn Earth made its own water, study suggests

'We learned something new about our own planet by looking at a large dataset of exoplanets.'

Contrary to a popular theory that icy comets or asteroids delivered water to a dry newborn Earth, the planet itself may have produced its earliest water supply, a new study suggests.

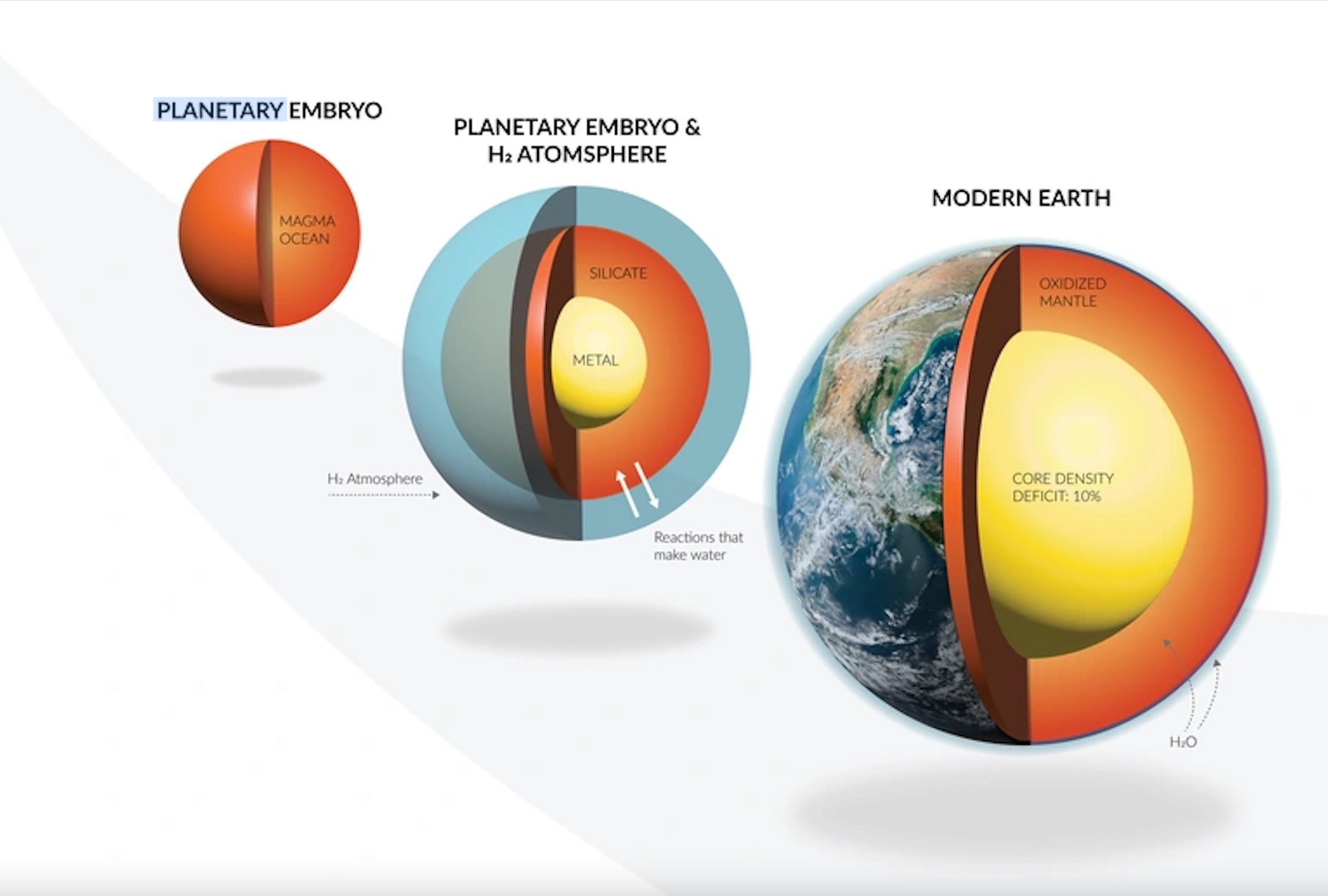

This water would have stemmed from chemical interactions between an atmosphere rich in hydrogen, which researchers think enveloped the young Earth, and massive oceans of magma on the planet's surface.

In these conditions, "water forms as a natural byproduct of all the chemistry that takes place," study co-author Anat Shahar, a scientist at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington D.C., told Space.com.

Related: How did Earth form?

Earth's uniqueness in the solar system is partly due to the abundant water that dominates over 70% of its surface, which is a lot more than any other planet in our cosmic neighborhood. Yet, when and where so much water came from remains an ongoing mystery for which scientists have not yet found a direct, conclusive answer.

One popular theory posits that asteroid impacts likely delivered most of the planet's water, but some research has shown that the water locked inside asteroids is chemically different from the water on Earth. Now, scientists say the abundant water supply that made Earth the watery world it is today arose thanks to a hydrogen-rich atmosphere early in the planet's history.

According to the latest study, homegrown water would be the outcome if the newborn proto-Earth was 0.2 to 0.3 times the planet's current size — slightly bigger than previously thought. (Earth continued to grow, of course, accumulating more and more surrounding gas and dust.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In that case, the young Earth would have been massive enough to hold onto its atmosphere for a long time, such that it would have been far richer in hydrogen than the trace amounts we see today. (Earth's current atmosphere is 78% nitrogen; hydrogen comprises just less than one part per million of the planet's protective blanket).

"Simply by changing the early conditions with which Earth formed, we are able to produce lots of water that goes both into the planet and into its atmosphere," Shahar told Space.com

Such hydrogen-rich atmospheres are regularly spotted around many newly formed rocky planets beyond our solar system. The most common types of exoplanets are super-Earths — worlds bigger than Earth but smaller than Neptune — and the ice giant's smaller cousins called mini-Neptunes. Astronomers have previously found that the atmospheres of some of these exoplanets have traces of water vapor, even on worlds that have high temperatures and pressures.

Young exoplanets commonly host hydrogen-rich atmospheres "during their first several million years of growth," Shahar said in a statement. "Eventually these hydrogen envelopes dissipate, but they leave their fingerprints on the young planet's composition."

So rather than learning about exoplanets by studying Earth, Shahar's team reversed the norm by treating Earth as an exoplanet instead to understand its early years in a new way. Tapping into the findings from exoplanet studies, the team simulated a hydrogen envelope around a young Earth and studied what that would mean for the planet's evolution.

"What we found is that by simply treating Earth as an exoplanet (surrounded by hydrogen) we were able to explain many of Earth's characteristics, including its water content," Shahar told Space.com.

For the study, researchers developed a model to study 25 compounds and 18 different chemical reactions. They found that massive amounts of hydrogen from the atmosphere would have blended with the molten magma oceans on the surface below, which later solidified to form Earth's largest and thickest layer, the mantle. The planet's abundant water stock then formed as a simple consequence of these chemical reactions, they found.

The team says such movement of light hydrogen molecules from Earth's atmosphere into its molten interior early in Earth's history answers two long-standing open questions: How large amounts of liquid water came to exist on Earth's surface and why the planet's core, which is mostly iron, is less dense than what scientists think it should be.

"We learned something new about our own planet by looking at a large dataset of exoplanets," Shahar told Space.com. "Answering the question from the lens of both Earth science and astronomy was key!"

The new study was published Wednesday (April 12) in the journal Nature.

Follow Sharmila Kuthunur on Twitter @Sharmilakg. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social

-

John R. I think that is more sensible/logical than it was transported here by whatever other means. The comets have shown to be not a dirty snowball so they got ruled out and asteroid's from what I read are not balls of ice and snow so include them out also. Lets give Earth some credit maybe things were made or originated here.Reply -

Helio The more asteroids and comets are studied, the better idea of how much they did contribute to our water volume. The deuterium ratios are pointing to something like about 1/3 coming from the icy bodies beyond Mars.Reply

The great impact (Theia) story that threw-off enough mass to make the Moon would have had quite an effect on our atmosphere. This wasn't mentioned, however. -

Broadlands It's a big assumption about all that hydrogen. Water in the stratosphere would photodissociate with the more intense solar UV and the hydrogen lost to space. That's what created oxygen and ozone to protect the evolution of life in the early Archean.Reply -

josh I think that the water was a byproduct of the ongoing nuclear reaction continuing in our core. This would explain many things about our planet, like how helium is still being produced and other elements and compounds still being formed.Reply