See Mercury shine bright while far from the sun on Saturday (Oct. 8)

The smallest planet in the solar system will be in its half-illuminated phase on Saturday.

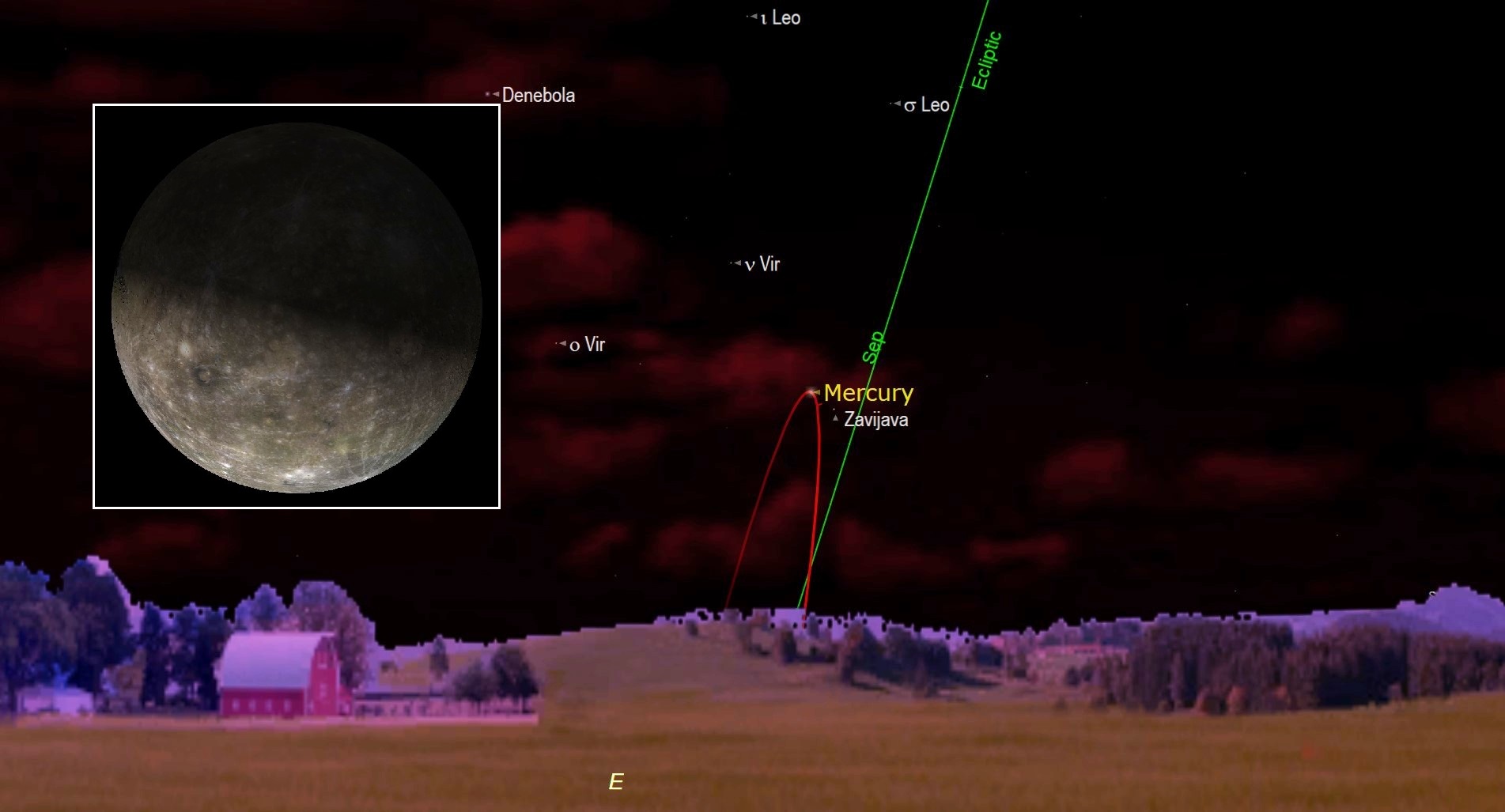

In the northern hemisphere on Saturday morning (Oct 8.), Mercury will appear in the sky with its disc half lit by the sun. This intermediate phase between the tiny planet being fully lit and totally dark is called 'Mercury at dichotomy.'

Mercury would often be difficult to see in the sky because it lies so close to the sun. This proximity means that glare from our star hides the glow from the solar system's smallest planet.

At the same time as Mercury is at dichotomy, however, it is also at its greatest elongation west. This is the phase of Mercury's journey across that sky at which it is furthest from the sun at sunset. As a result, the planet is more visible than usual.

Related: Night sky, October 2022: What you can see tonight [maps]

On Saturday at sunset when it is close to half illuminated, Mercury will be around 18 degrees from the sun in the sky and will be around 7 arcseconds wide, according to EarthSky. The planet will be in the constellation of Virgo.

Mercury will be at a magnitude of around -0.5 on Saturday but following this, it will brighten throughout October. The tiny planet will reach a magnitude of around -1.1 by the end of the month when its disk will be fully illuminated. (The lower an object's magnitude, the brighter it appears to the naked eye.)

Mercury's inferiority complex

Like Venus, Mercury is called an 'inferior planet' by astronomers. This refers to the fact that both planets are closer to the sun than our planet and are inside Earth's orbit. Superior planets — those worlds outside Earth's orbit like Mars and Jupiter — are always full or close to full in the sky.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

On the other hand, inferior planets have a complete range of phases that are similar to those of the moon. The phases of Mercury have a cycle that lasts around 116 days and they are determined by the planet’s position relative to the Earth.

As Mercury passes between our planet and the sun, the side facing the surface of Earth is not illuminated and is thus completely dark — analogous to the moon during its new moon phase.

Looking for a telescope to observe Mercury? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

When Mercury is on the other side of Earth, the tiny planet's disk is completely illuminated — similar to a full moon. But at this point, Mercury is also at its greatest distance from Earth which has the effect of counterintuitively making it appear more fully lit than at other times.

Mercury is at a thinly illuminated crescent phase when it is on the Earth's side of the sun. When Mercury is on the far side of the sun it is in a gibbous phase, during which the illuminated region of its disk is greater than a semicircle but less than a full circle.

Mercury's half-illuminated phase — dichotomy — usually falls around the time of the greatest elongation. The two notable astronomical events of Mercury can occur within a few days of each other, but during October 2022 will happen on the same day.

If you're interested in seeing Mercury at its brightest, don't miss our guides for the best binoculars deals and the best telescope deals. If you're looking to get into photographing the wonders of the night sky, make sure not to miss our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography guides.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.