Nobody Knows What Made the Gargantuan Crater on the Dark Side of the Moon

Scientists just debunked the most popular explanation for one of the solar system's largest craters.

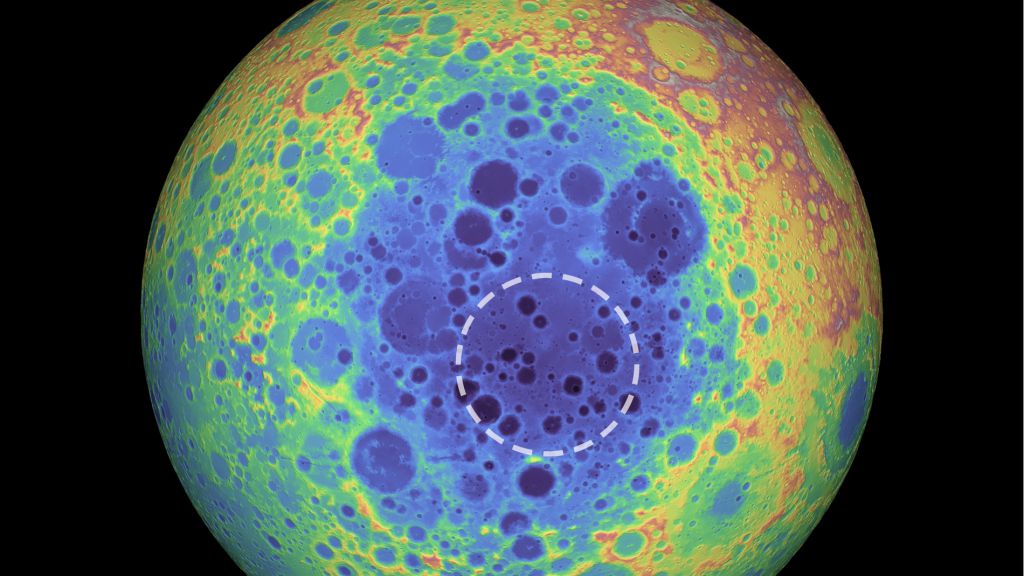

Billions of years ago, something slammed into the dark side of the moon and carved out a very, very large hole. Stretching 1,550 miles (2,500 kilometers) wide and 8 miles (13 km) deep, the South Pole-Aitken basin, as the tremendous hole is known to Earthlings, is the oldest and deepest crater on the moon, and one of the largest craters in the entire solar system.

For decades, researchers have suspected that the gargantuan basin was created by a head-on collision with a very large, very fast meteor. Such an impact would have ripped the moon's crust apart and scattered chunks of lunar mantle across the crater's surface, providing a rare glimpse at what the moon is really made of. (Spoiler: It's not cheese.) That theory gained some credence earlier this year, when China's Yutu-2 rover, which settled into the bottom of the crater aboard the Chang'e 4 lander in January, discovered traces of minerals that seemed to originate from the moon's mantle.

Now, however, a study published Aug. 19 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters throws those results — and the crater's origin story — into question. After analyzing the minerals in six plots of soil at the bottom of the South Pole-Aitken basin, a team of researchers argues that the crater's composition is all crust and no mantle, suggesting that whatever impact opened the crater billions of years ago did not hit hard enough to spray the moon's innards onto the surface.

Related: 5 Strange, Cool Things We've Recently Learned About the Moon

"We are not seeing the mantle materials at the landing site as expected," study co-author Hao Zhang, a planetary scientist at the China University of Geosciences, said in a statement. These findings all but rule out a direct collision with a high-velocity meteor and raise the question: What, if not a head-on meteor strike, created the largest crater on the moon?

Lighting up the dark side

In their new study, the researchers used a technique called reflection spectroscopy to identify specific minerals in the lunar soil based on how individual grains reflected visible and near-infrared light.

Using equipment aboard the Yutu 2 rover, the team conducted reflectance tests on six patches of soil in the first two days following Chang'e 4's landing, venturing about 175 feet (54 meters) away from the lander. With the help of a database that identifies lunar minerals based on a variety of factors — including size, reflectance and degradation due to solar wind — the team estimated the mineral concentration in each of the plots.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A crystalline rock called plagioclase was by far the most abundant mineral in each sample, accounting for 56% to 72% of the crater's composition, the researchers wrote. Formed as primordial oceans of lava cool, plagioclase is extremely common in the crusts of Earth and the moon alike, but it's less abundant in their mantles. Though the team detected other minerals in the crust that are more common in the moon's mantle, such as olivine, these rocks made up too small a fraction of the soil samples to suggest that part of the mantle had broken through the crust.

This mineral makeup complicates the theory that a giant, high-velocity meteor created the South Pole‐Aitken basin billions of years ago, as such an impact almost certainly would have scattered chunks of mantle over the lunar surface.

So, what, then, created the crater? The researchers did not speculate in the new study. However, prior research has suggested that a renegade space rock is still the culprit, but the hit may not have been so direct. A study published in 2012 in the journal Science argued that a slightly slower-moving meteor could have struck the back of the moon at an angle of about 30 degrees and resulted in an appropriately large crater that never disturbed the moon's mantle. However, those researchers had only simulations to go on.

If nothing else, the new research suggests that there's a lot more exploring to do in the South Pole‐Aitken basin before an answer becomes apparent. See you on the dark side of the moon.

- Crash! 10 Biggest Impact Craters on Earth

- The 12 Strangest Objects in the Universe

- 10 Interesting Places in the Solar System We'd Like to Visit

Originally published on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Brandon has been a senior writer at Live Science since 2017, and was formerly a staff writer and editor at Reader's Digest magazine. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.