Aurora alert: Possible geomagnetic storm could bring northern lights as far south as New York

Northern lights could be visible over some northern and upper Midwest states.

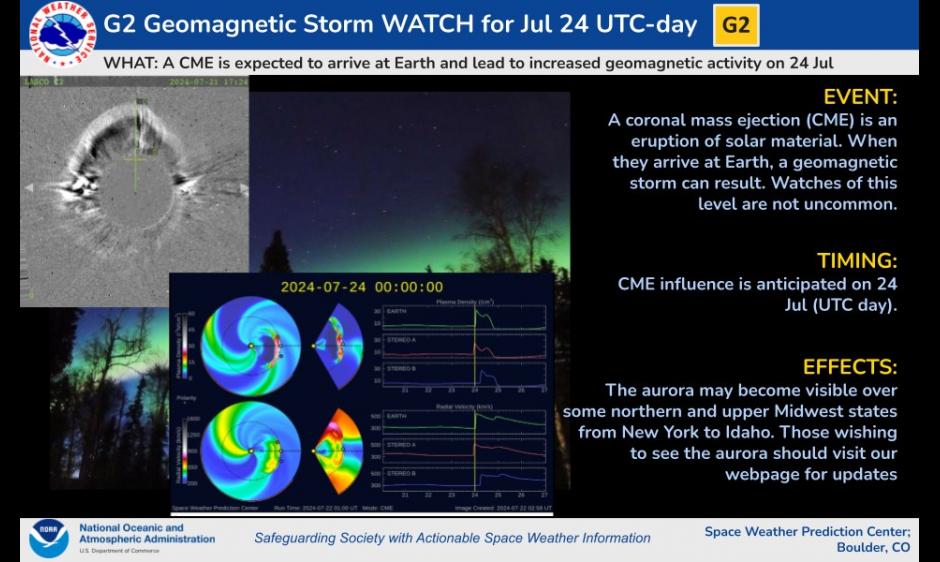

Heightened solar activity has prompted the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Space Weather Prediction Center to issue a geomagnetic storm watch for July 24.

The culprit? A plume of plasma and magnetic field known as a coronal mass ejection (CME) that was released from the sun on Jul 21 and is now barreling toward Earth and due to arrive on July 24.

Recent predictions anticipate the arrival window in the early hours of July 24, but there is a level of uncertainty about the exact timings. "Likely the storm will be fashionably late, due to slow solar wind "traffic" & an additional glancing storm blow ahead of it," space weather physicist Tamitha Skov wrote in a post on X.

CMEs carry with them electrically charged atoms known as ions, when CMEs collide with Earth's magnetosphere they can trigger geomagnetic storms. During geomagnetic storms the ions collide with gases in Earth's atmosphere and release energy in the form of light, we recognize this as the northern lights or aurora borealis in the Northern Hemisphere or the southern lights, or aurora australis in the Southern Hemisphere.

Geomagnetic storms are classified by NOAA using a G-scale to measure the intensity of geomagnetic storms. They range from G5, the most extreme class to G1 minor class storms. The recent geomagnetic storm watch issued by NOAA is currently classified as a G2-class.

Like weather on Earth, space weather is a fickle creature and difficult to predict. Geomagnetic storm warnings like this are not uncommon and in some cases, they fizzle to nothing. As we get closer to July 24 space weather forecasters will gain a better idea of when (if at all) to expect the CME to arrive.

Though aurora chasers will be willing on the arrival of the CME and have everything crossed for a direct hit, this isn't a sentiment shared by all.

CMEs can wreak havoc on our technological world and pose a threat to both satellites and astronauts in low Earth orbit. On Earth, CMEs can cause surges in electrical currents which can overload power grids, causing blackouts. They can also jostle Earth's magnetic field and disrupt radio transmissions and increase radio static in Earth's ionosphere.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In space, high-energy particles from the CME can damage satellites in low-Earth orbit. CMEs can also cause Earth's atmosphere to warm and expand, as it does it creates a thicker medium through which a satellite must travel, the additional drag can slow a satellite's momentum and lead to a lowering of its orbit.

Astronauts also receive a higher dose of radiation during a CME event compared to if they were on Earth, though they are still mostly protected by the magnetosphere and shielded by the structure of the spacecraft.

For the latest space weather alerts and forecast check out NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center.

This article was updated on July 23 to include the recent prediction of the CME arrival window and the quote from Tamitha Skov's post on X.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Daisy Dobrijevic joined Space.com in February 2022 having previously worked for our sister publication All About Space magazine as a staff writer. Before joining us, Daisy completed an editorial internship with the BBC Sky at Night Magazine and worked at the National Space Centre in Leicester, U.K., where she enjoyed communicating space science to the public. In 2021, Daisy completed a PhD in plant physiology and also holds a Master's in Environmental Science, she is currently based in Nottingham, U.K. Daisy is passionate about all things space, with a penchant for solar activity and space weather. She has a strong interest in astrotourism and loves nothing more than a good northern lights chase!