Stellar oddball: Nearby star rotates unlike any other

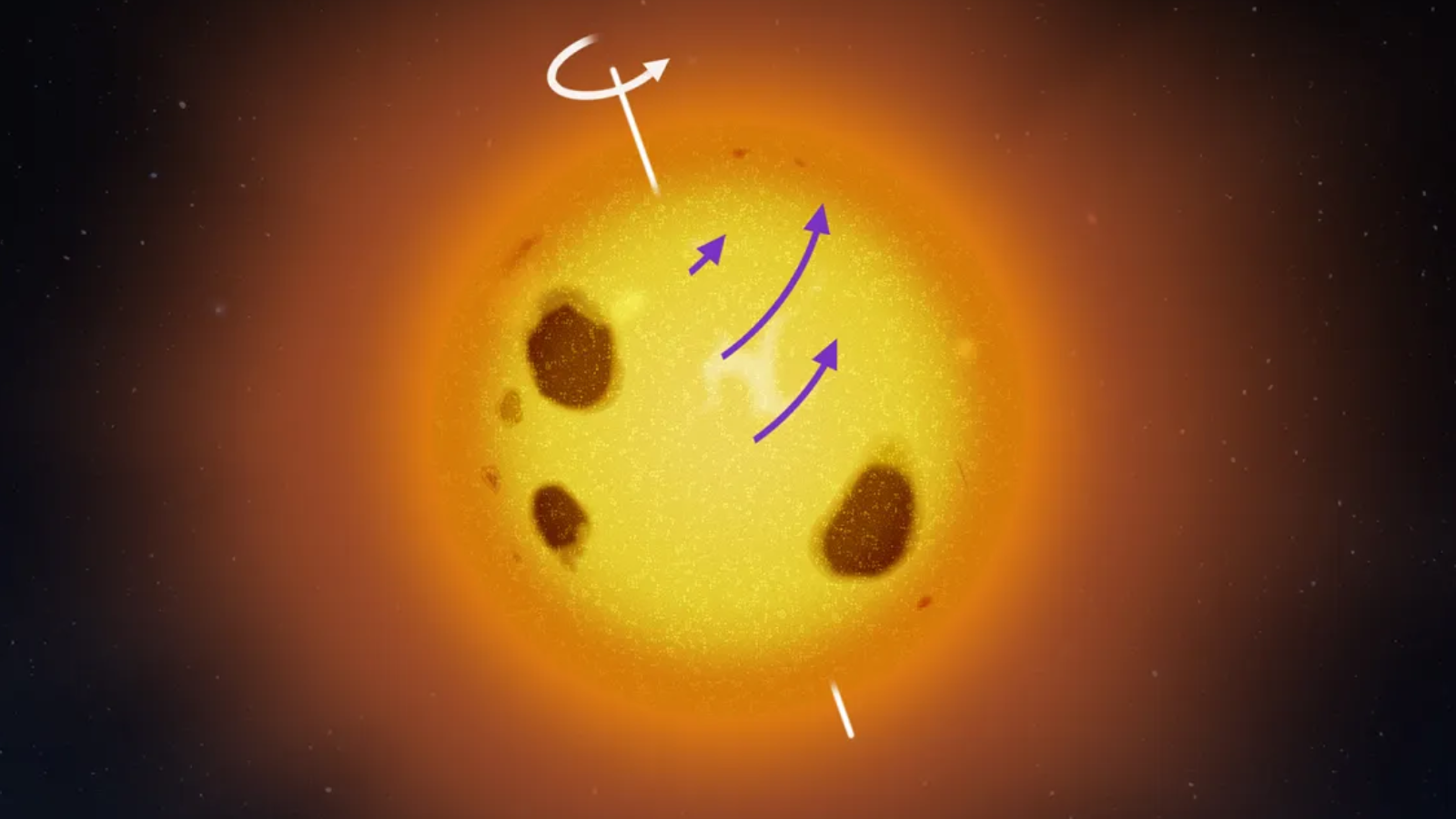

V889 Herculis doesn't rotate like any other star, defying stellar models.

A nearby star that's similar to the sun in many ways is actually an unprecedented oddball, astronomers have discovered.

The surprising star is V889 Herculis, located 115 light-years away in the constellation of Hercules. This otherwise sun-like young star spins in a way that astronomers have never seen before and could challenge our model of stellar rotation, which scientists had thought was well understood.

Stars are roiling balls of superheated gas or plasma, meaning they don't rotate like solid bodies. Instead, they display differential rotation; some layers move at different speeds than others. For example, the sun rotates fastest at its equator, slower at increasing latitudes and slowest at its poles.

V889 Herculis, on the other hand, rotates fastest at a latitude of around 40 degrees. Its poles rotate more slowly, as expected, but its equator also rotates slowly, which is something not predicted even in speculative computer simulations. As a 50 million-year-old star, V889 Herculis could tell us a great deal about the evolution of our 4.6 billion-year-old sun, researchers said.

Related: The building blocks of life can form rapidly around young stars

"We applied a newly developed statistical technique to the data of a familiar star that has been studied in the University of Helsinki for years," team coordinator Mikko Tuomi said in a statement.

"We did not expect to see such anomalies in stellar rotation," Tuomi added. "The anomalies in the rotational profile of V889 Herculis indicate that our understanding of stellar dynamics and magnetic dynamos are insufficient."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Dynamics of an oddball

Understanding stellar rotation is important for many reasons. Not only can it shed light on the evolution of stars, but robust rotational models can also help predict activity-based effects such as sunspots, coronal mass ejections (CMEs), and solar flares on our own sun.

The rotation of stars is difficult to understand because of the dynamic processes that occur within them. Stars exist in a finely balanced equilibrium between the inward push of their own gravity and the outward pressure of energy generated in their cores. The nuclear fusion of hydrogen to helium in the core of a star generates this energy and heat, the latter of which is carried through the star by the rising of heated plasma and the fall of cooled plasma, a process called convection. Convection helps give rise to a star's differential rotation by influencing local rates of rotation.

Other factors are at play in differential rotation, such as the mass of a star, its age, composition, rotational period (the time it takes to fully revolve), and even its magnetic field.

"Stellar differential rotation is a very crucial factor that has an effect on the magnetic activity of stars," University of Helsinki astronomer Thomas Hackman said in the same statement. "The method we have developed opens a new window into the inner workings of other stars."

The team used their modeling method and 30 years of observations from Fairborn Observatory in Arizona to determine the rotational profile of V889 Herculis and another nearby young star, LQ Hydrae, located around 60 light-years from Earth in the constellation of Hydra. The latter star, also around 50 million years old, rotates just as astronomers would expect, in a fashion similar to the sun's rotation.

Tuomi credited senior astronomer Gregory Henry of Tennessee State University for the observations used in the testing of their model and for aiding the discovery of this shocking star.

"For many years, Greg's project has been extremely valuable in understanding the behavior of nearby stars. Whether the motivation is to study the rotation and properties of young, active stars or to understand the nature of stars with planets, the observations from Fairborn Observatory have been absolutely crucial," Tuomi concluded. "It is amazing that even in the era of great space-based observatories, we can obtain fundamental information on stellar astrophysics with small 40-centimeter ground-based telescopes."

The team's research has been accepted for publication in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

-

AboveAndBeyond How can they resolve the rotation at differing latitudes in these distant stars?Reply