NASA's Opportunity Mars rover didn't just luck into its amazing longevity.

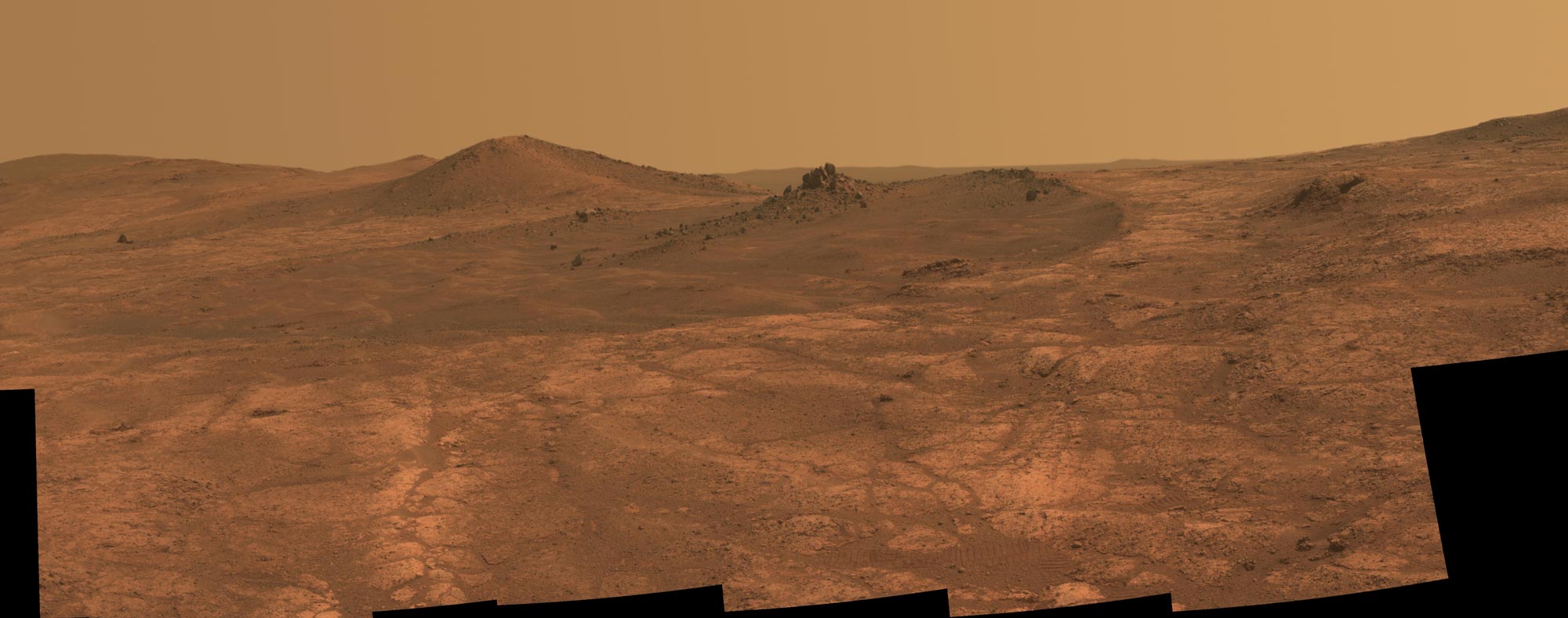

The golf-cart-size Oppy and its twin, Spirit, landed on the Red Planet a few weeks apart in January 2004, tasked with 90-day missions to look for signs of past water activity. Spirit explored its patch of Mars until 2010, and Opportunity kept rolling until a monster dust storm boiled up around the rover this past June.

NASA tried to revive Oppy for more than eight months but finally threw in the towel yesterday (Feb. 13), officially declaring an end to the two robots' Mars Exploration Rover (MER) mission. [Postcards from Mars: The Amazing Photos of Opportunity and Spirit Rovers]

A combination of factors made it possible for the solar-powered Spirit and Opportunity to exceed their warranties so spectacularly, said MER project manager John Callas, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California.

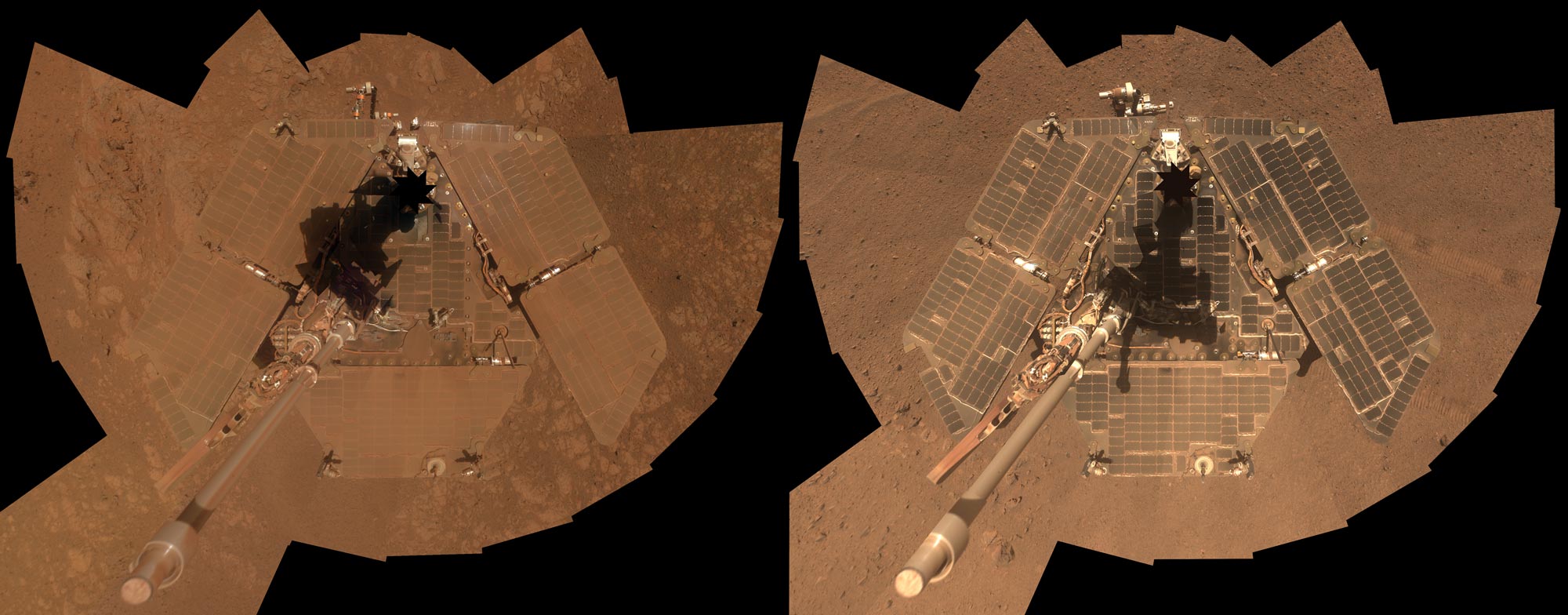

One of these was the Martian weather. The mission team planned for a 90-day life for the rovers because it was thought that it would take about that long for falling dust to blanket the duo's solar panels, effectively choking them out. But strong winds came along and blasted both robots' arrays clean before the robots had to face down their first Martian winter.

And these helpful cleaning events kept happening.

"This, on a seasonal cycle, actually became pretty reliable and allowed us to survive not just the first winter but all the winters we experienced on Mars and to keep going and exploring," Callas said yesterday during a ceremony at JPL announcing the end of the MER mission.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The rovers also had "the finest batteries in the solar system," Callas added. Opportunity's main battery weathered more than 5,000 charge-discharge cycles and still had about 85 percent of its capacity left when the mission-ending dust storm hit, he said.

Together, the dust-clearing winds and the batteries "allowed us to have the critical energy we needed to get through the coldest, darkest parts of the winter on Mars and to keep exploring," Callas said.

Great engineering wasn't limited to the batteries, of course. All the other pieces of Spirit and Opportunity, from their electronic brains to their grippy wheels to their scientific instruments, were built to last. And they did so for an impressively long time, on a cold, dry, radiation-blasted world millions of miles from Earth.

The rovers' handlers deserve a great deal of credit as well, NASA officials have stressed. Both Spirit and Opportunity got into some sticky situations that required creativity, determination and long hours to rectify. In 2005, for example, Opportunity got stuck in the soft sand of a formation the mission team dubbed Purgatory Dune. Oppy's handlers tested possible solutions in a Mars-simulating "sandbox" at JPL and managed to extricate the rover after several stressful weeks.

In addition, the team often drove Opportunity backward to extend the operational life of its right front wheel, which sometimes drew more than its share of electric current.

"We were innovative in problem-solving and figuring out ways how to keep this rover going and how to keep it productive and to continue that exploration and scientific discovery," Callas said.

So, what finally killed the two robotic pioneers?

In 2009, Spirit got trapped in some soft sand. The team tried repeatedly to free the rover but could not do so, and Spirit ended up enduring a harsh winter without the ability to reorient itself to catch some crucial sun. The rover — which last communicated with Earth in 2010 and was officially declared dead in 2011 — essentially froze to death, NASA officials have said.

And Opportunity was done in by an epic, planet-shrouding dust storm. The rover had ridden out several other maelstroms, but the historic storm of 2018 proved to be too much. [Mars Dust Storm 2018: What It Means for Opportunity Rover]

Intriguingly, Opportunity might have been able to weather this one, too, if not for a glitch that occurred just after landing in 2004. Back then, a heater on the rover's robotic arm got stuck in the "on" position, Callas explained. Oppy's handlers decided to shut down everything on the rover — including its survival heaters — every night so that this one wonky heater wouldn't drain away crucial battery power.

"The rover would get cold, but it would stay just warm enough that, in the morning, when the sun would come up and we would power everything back up, it never got below its allowable temperatures," Callas said of this "deep sleep" strategy.

If the team hadn't taken this measure, Opportunity likely wouldn't have lasted long beyond its originally prescribed 90-day life, he added.

When Opportunity lost power during the 2018 dust storm, however, its mission clock likely got scrambled, preventing the rover from knowing when to enter deep-sleep mode, Callas said.

"So, it probably wasn't sleeping at night when it needed to, and that heater was stuck on, draining away whatever energy the solar arrays were accumulating from the sun to charge those batteries," he said. "That might be part of the explanation, in addition to the fact that now it's much colder and darker on Mars."

Regardless of the details, both Spirit and Opportunity died honorable deaths on the Red Planet, said MER principal scientific investigator Steve Squyres, of Cornell University in New York. And the mission's scientific contributions are immense; both rovers found lots of evidence that Mars was wet billions of years ago, reshaping our understanding of the planet's evolution and its past potential to host life. Indeed, Spirit even found an ancient hydrothermal system, showing that at least some parts of the Red Planet once featured both liquid water and an energy source — two requirements for life as we know it.

So, Squyres said, he feels good about Opportunity's death and the conclusion of the MER mission.

"If it's going to end, having it end like this — that's fine," he told Space.com.

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.