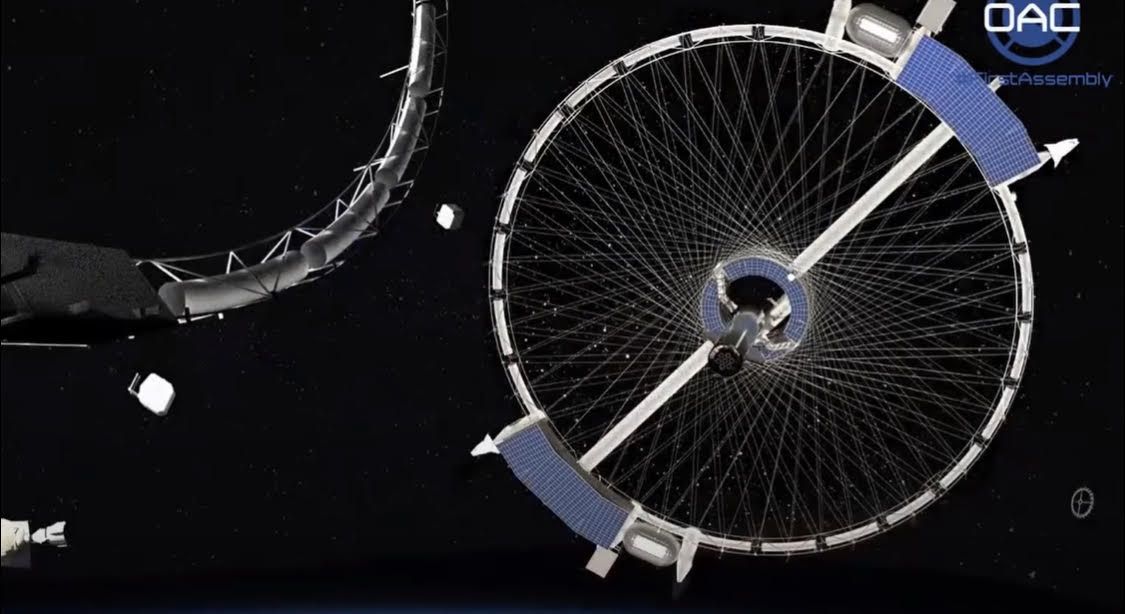

Orbital Assembly Corporation (OAC) recently unveiled new details about its ambitious Voyager Station, which is projected to be the first commercial space station operating with artificial gravity.

OAC, a manufacturing firm centered on the colonization of space, discussed Voyager Station during a video press junket late last month. The Jan. 29 "First Assembly" virtual event served as an update for interested investors, marketing partners and enthusiastic vacationers hoping to someday book a room aboard the rotating Voyager Station.

The project's roots go back a number of years.

In pictures: Private space stations of the future

John Blincow established The Gateway Foundation in 2012. The organization's plans include jumpstarting and sustaining a robust and thriving space construction industry, first with the Voyager Station and The Gateway commercial space station — "important first steps to colonizing space and other worlds," the foundation's website states. OAC was founded by the Gateway Foundation team in 2018 as a way to help make these dreams come true.

The hour-long Jan. 29 presentation and Q&A session was hosted by OAC medical advisor Shawna Pandya and streamed live on the company's YouTube channel. During the event, the space construction company revealed its schedule for the next chapter of human space exploration.

Its team of skilled NASA veterans, pilots, engineers and architects intends to assemble a "space hotel" in low Earth orbit that rotates fast enough to generate artificial gravity for vacationers, scientists, astronauts educators and anyone else who wants to experience off-Earth living.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

As a multi-phase endeavor requiring funds to realize the dream, OAC is now officially open for private investors to purchase a stake in the company at $0.25 per share, until April 1, 2021.

Voyager Station is patterned after concepts imagined by legendary rocket scientist Wernher von Braun, one of the main orchestrators of NASA's Apollo program. The 650-foot-wide (200 meters) wheel-shaped habitat will spin with an angular velocity high enough to create moon-like levels of artificial gravity for occupants.

Lunar legacy: 45 Apollo moon mission photos

If realized, Voyager would become the biggest human-made structure in space, fully equipped to accommodate up to 400 people. Assembly is scheduled to begin around 2025, Gateway Foundation representatives said.

This shining technological ring will feature amenities ranging from themed restaurants, viewing lounges, movie theaters and concert venues to bars, libraries, gyms, and a health spa.

Voyager will house 24 integrated habitation modules, each of which will be 65 feet long and 40 feet wide (20 by 12 meters). At near-lunar gravity, the rotating resort will have functional toilets, showers, and allow jogging and jumping in fun and novel ways.

But before the station can start spinning, its builders must establish the necessary orbital infrastructure and create smaller structures to test the concept.

Blincow explained during the Jan. 29 event that the current plan is to build the rotating space station in stages, beginning with a small-scale prototype station, in addition to a free-flying microgravity facility, both using Voyager components.

"This will be the next industrial revolution," Blincow said.

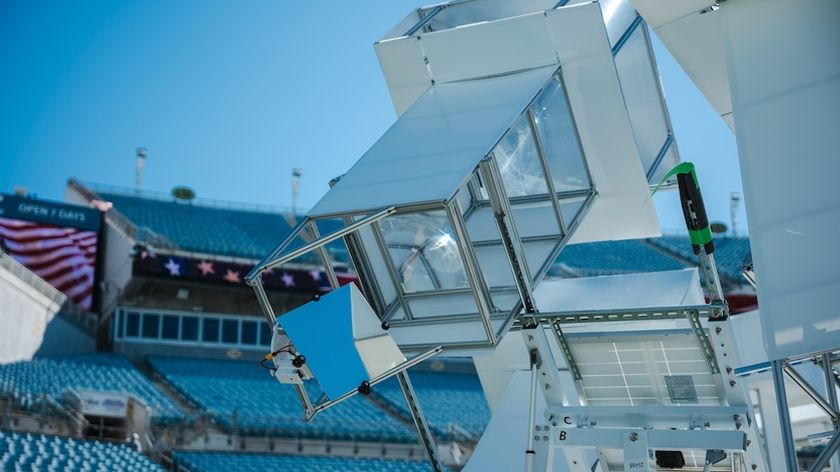

Eventually, a Structure Truss Assembly Robot (STAR) will fabricate the frame of the Voyager and Gateway stations in orbit. Prior to that happening, however, a smaller, ground-based prototype, known as DSTAR, will test the technology here on Earth.

OAC's truss assembly robot stands to be the first to build a space station in low Earth orbit and will serve as "the structural backbone of future projects in space," OAC fabrication manager Tim Clements said during the event.

Currently, the machine is undergoing commissioning and shipping. It will then be completed and tested in California.

"The prototype will produce a truss section roughly 300 feet [90 m] in length in under 90 minutes," Clements revealed during the live-streamed event. "DSTAR weighs almost 8 tons in mass, consisting of steel, electrical and mechanical components."

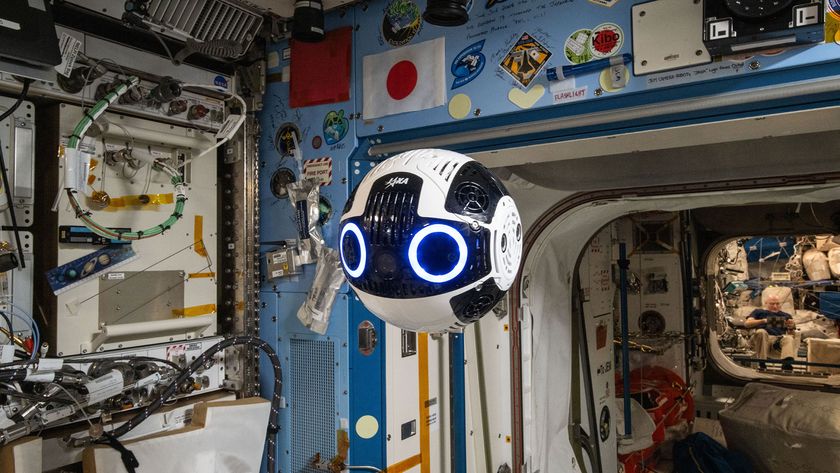

OAC is also creating a robotic observer drone for remote viewing via a virtual reality headset as its first in-house development project.

"It's going to be our eyes on the job site," said Tim Alatorre, Gateway Foundation executive team member one of the station's designers. "The observer drone operates in a support function. It can perch on existing craft. It can also be fully reusable and can fly and have a free-flight mode on extended missions."

Long before Voyager Station can start accommodating guests, OAC needs to test both building a station in low Earth orbit and prove the viability of stable artificial gravity in space. The company plans to construct a prototype gravity ring that will measure 200 feet (61 m) in diameter and will be engineered to spin up to create artificial gravity near Mars' level, which is about 40% that of Earth.

"The gravity ring is going to be a key technology demonstration project that we plan to build, assemble and operate in low Earth orbit in just a few years' time," said OAC co-founder Jeff Greenblatt. "The company also plans to use an orbital version of the DSTAR called the PSTAR, which stands for Prototype Structural Truss Assembly Robot."

This gravity ring will act as a "near-term demonstrator," which will take two to three years to build and launch. Once installed in orbit, its assembly will take just three days. This structure will act as the company’s test base for many of the technologies to be used to build Voyager Station.

"We haven't seen an explosion of commercial activity in space," Alatorre said. "The cost has been about $8,000 per kilogram [$3,600 per lb.] for a long time. But with the Falcon 9, you can do it for less than $2,000. And as Starship comes online, it will only cost a few hundred dollars." (These were references to SpaceX launchers — the company's workhorse Falcon 9 rocket and its Starship Mars vehicle, which is in development.)

"Microgravity is just brutal on our bodies," Alatorre added "We need artificial gravity — a mechanism to give us a dosage of gravity to give us the ability to live long-term in space."

Related: Weightlessness and its effects on astronauts

The planned gravity ring may also become a research platform for international space agencies and private aerospace firms interested in the effects of partial artificial gravity on both non-living and living systems, OAC representatives said.

"This will give researchers an unprecedented opportunity to access that intermediate gravity regime," Greenblatt said. "This will then pave the way for OAC to build larger, more complex structures in space, which is obviously necessary if we're going to get to the point of building Voyager Station and other larger structures beyond."

Looking into the future, government and private companies will be allowed to use the Voyager modules for lunar training missions and beyond, providing a launch pad for entrepreneurs to develop and market tourist activities in space.

"We don't want the Voyager experience to be like being in an attack submarine in combat, so we're [building] for comfort," said Tom Spilker, OAC's chief technology officer and vice president of engineering and space systems design. "It's a bit smaller than the length of the U.S. Capitol building."

"Despite the seemingly endless list of luxury amenities, there will also be airlocks for visitors," Spilker added. "So anyone who can afford a space hotel can go on a private spacewalk, where the only thing between you and the universe is a faceplate."

Correction: A previous version of this story listed Gateway Foundation executive team member Tim Alatorre as the lead designer of the Voyager station project. He is one of the designers.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jeff Spry is an award-winning screenwriter and veteran freelance journalist covering TV, movies, video games, books, and comics. His work has appeared at SYFY Wire, Inverse, Collider, Bleeding Cool and elsewhere. Jeff lives in beautiful Bend, Oregon amid the ponderosa pines, classic muscle cars, a crypt of collector horror comics, and two loyal English Setters.