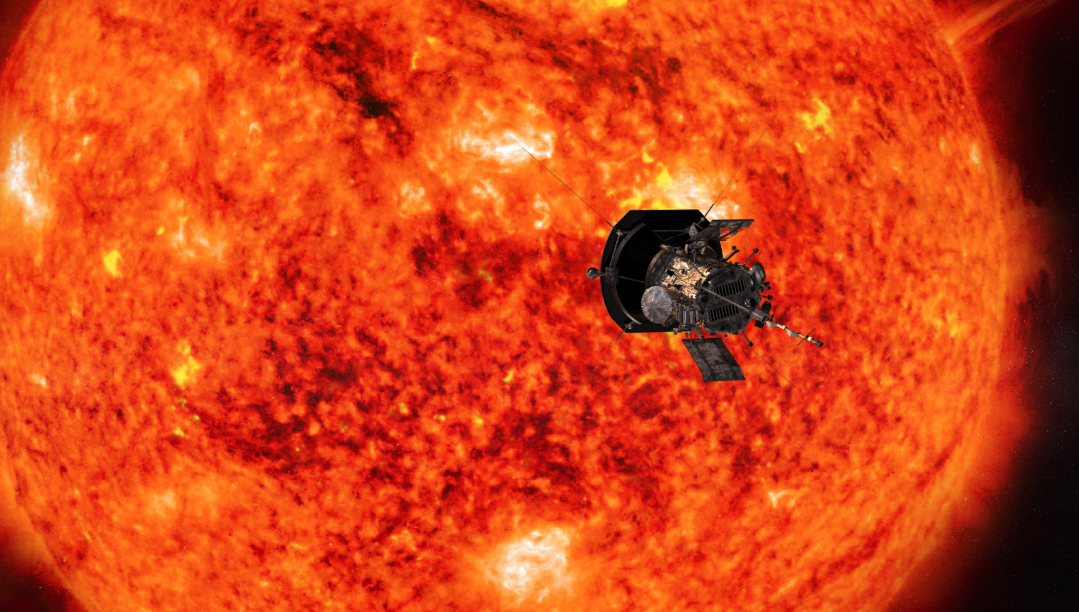

NASA's Parker Solar Probe flies by the sun in 5th close encounter

NASA's daring Parker Solar Probe made its fifth daring flyby of the sun this weekend.

The spacecraft has been conducting a marathon of solar observations since May 9 as scientists affiliated with the mission look to crack more secrets about how the sun works. The observations will continue until June 28, totaling more than seven weeks of measurements during the probe's fifth swing past the sun.

The closest approach of this orbit, called a perihelion, occurred at 4:23 a.m. EDT (0823 GMT) on Sunday, June 7. At that time, the probe was about 11.6 million miles (18.7 million kilometers) from the sun's surface and was travelling at over 244,000 mph (393,000 km/h) relative to the sun.

Related: What's inside the sun? A star tour from the inside out

Parker Solar Probe launched in August 2018 on a mission to study the sun's outer atmosphere, called the corona. Parker Solar Probe is outfitted with four different instrument suites to try to solve two key mysteries that the corona poses for scientists who want to understand the workings of our star and others like it.

First, the corona incredibly hot, millions of degrees no matter which scale you use and far hotter than the visible surface of the sun. Scientists want to understand how this region achieves such eye-watering temperatures. Second, the corona serves as a launch pad for the solar wind, the stream of charged particles that flows off the sun and across the solar system. The solar wind reaches incredible speeds in the corona, and scientists also want to understand how that process occurs.

This weekend's fifth perihelion is also the prelude to another intriguing event. On July 10 (July 11 GMT), the Parker Solar Probe will conduct a flyby of Venus. The maneuver is one in a series that is vital to send the spacecraft closer toward the sun, giving the probe ever-closer views of the star during perihelion passes.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But the July flyby will also be a prime opportunity to study Earth's neighbor, as the spacecraft will pass just 517 miles (832 km) above the surface of Venus. In particular, this flyby should give scientists vital information about how the atmosphere of Venus dribbles away from the planet in what scientists call its tail. It's the sort of bonus science that missions love.

And the flyby will nudge Parker Solar Probe closer to its main target during subsequent perihelion maneuvers. By the end of the mission, in late 2025, the spacecraft will be soaring just 4 million miles (6 million km) away from the sun's surface.

- NASA's Parker Solar Probe mission to the sun in pictures

- What's inside the sun? A star tour from the inside out

- NASA sun probe spies the solar wind in 1st birthday photo

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.

-

newtons_laws The article says "This weekend's fifth perihelion is also the prelude to another intriguing event. On July 10 (July 11 GMT), the Parker Solar Probe will conduct a flyby of Venus. The maneuver is one in a series that is vital to speed the spacecraft up enough to continue creeping toward the sun, giving the probe ever-closer views of the star during perihelion passes. "Reply

Actually as the spacecraft flies by Venus each time it DECREASES the speed of the spacecraft relative to the Sun so that the spacecraft orbit takes it closer to the Sun. The velocity of the spacecraft at perihelion (closest point of approach to the Sun) does however get bigger as the perihelion gets closer to the Sun. Simple orbital mechanics. ;)

Edit: I see the article has now been edited to correct this, thanks. :)