SAN FRANCISCO — NASA's record-breaking Parker Solar Probe (PSP) has given us a new perspective on a famous meteor shower.

In a cosmic first, PSP imaged the dusty trail of debris that causes the Geminid meteor shower, which peaks this weekend. Astronomers already knew that this stream was shed by the 3.7-mile-wide (6 kilometers) asteroid Phaethon, but they had never gotten a look at it before because it's so faint.

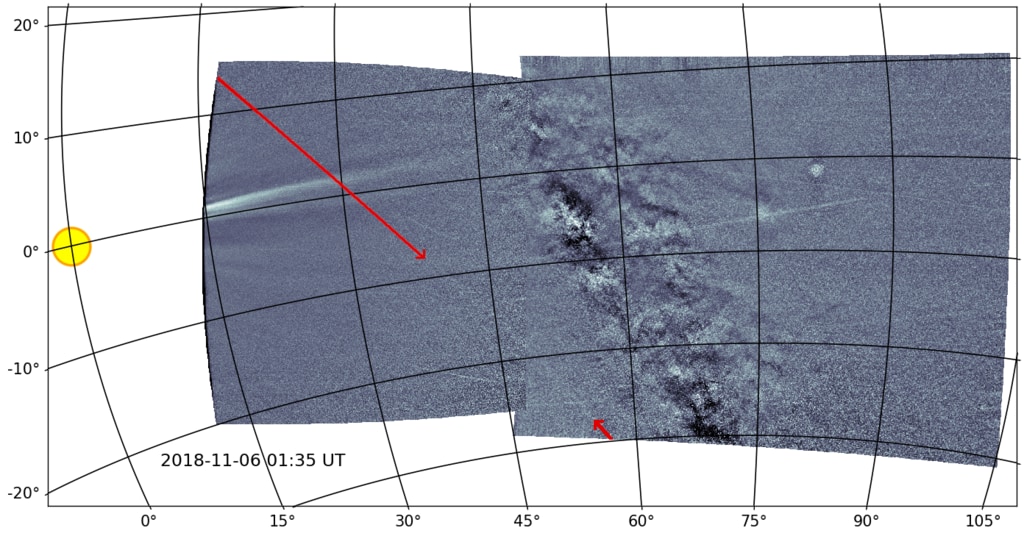

PSP's Wide-Field Imager for Solar Probe (WISPR) instrument did, however, detecting a structure about 12 million miles long and 60,000 miles wide (20 million km by 100,000 km) that follows Phaethon's highly elliptical path around the sun, mission team members announced here today (Dec. 11) at the annual fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU).

Related: Awesome Photos! The Geminid Meteor Shower of 2018 in Pictures

"We calculate a mass on the order of a billion tons for the entire trail, which is not as much as we'd expect for the Geminids, but much more than Phaethon produces near the sun," Karl Battams, a space scientist at the U.S. Naval Research Lab in Washington, D.C., said in a statement.

"This implies that WISPR is only seeing a portion of the Geminid stream — not the entire thing — but it's a portion that no one had ever seen or even knew was there, so that's very exciting!" he added.

The full Geminid stream extends over the entirety of Phaethon's orbit around the sun, which covers about 6 astronomical units (AU), Battam said during a press conference today here at AGU. (One AU is the average Earth-sun distance — roughly 93 million miles, or 150 million km.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The material in that stream was likely ejected in one dramatic event several thousand years ago, perhaps during one of Phaethon's close solar passes, he added. Those passes occur every 524 Earth days.

The newly announced Geminid results are pure gravy for the PSP, whose main target is of course the sun. Specifically, the mission aims to solve two long-standing solar mysteries: how the stream of charged particles flowing from the sun, known as the solar wind, attains such tremendous speeds; and why the sun's outer atmosphere, or corona, is so much hotter than its surface. (Temperatures in the corona can top 2 million degrees Fahrenheit, or 1.1 million degrees Celsius. The solar surface is about 11,000 F, or 6,000 C.)

The PSP gathers most of the required data during epic dives through the corona, which are taking the spacecraft closer to the sun than any human-made vehicle has ever gotten and accelerating the PSP to unprecedented speeds.

During its first few close solar passes, for example, the PSP has zoomed within 15 million miles (24 million km) of the solar surface at speeds in excess of 200,000 mph (320,00 km/h).

Related: NASA's Parker Solar Probe Mission to the Sun in Pictures

The spacecraft, which launched last August, has completed three such dives to date. But that's just the beginning; if all goes according to plan, the PSP will have performed two dozen of these "perihelion passes" before the $1.5 billion mission wraps up in 2025.

And the last few dives may well be the most revelatory. The spacecraft is using flybys of Venus to reduce its perihelion distance over time. By 2025, the PSP should get within a mere 3.83 million miles (6.16 million km) of the solar surface on closest approach — and be traveling about 430,000 mph (690,000 km/h) relative to our star at the time.

All that being said, the PSP has already made considerable progress toward its main mission goals. The team outlined that progress last week in a series of four papers, which detailed the PSP's first science results.

One of the major finds is the discovery of reversals, or "switchbacks," in the solar magnetic field lines in the corona. Such features were quite unexpected and may be integral to the solar wind and corona conundrums that the PSP is tackling, team members have said.

Researchers discussed those switchbacks and other PSP findings during today's press conference as well. One such finding is a newfound relationship between fast-moving solar energetic particles, which are accelerated away from the sun by bursts of radiation called solar flares, and the huge explosions of solar plasma known as coronal mass ejections.

"The regions in front of coronal mass ejections build up material, like snowplows in space, and it turns out these 'snowplows' also build up material from previously released solar flares," Nathan Schwadron, a space scientist at the University of New Hampshire, said in the same statement.

Overall, the future looks very bright for the PSP, Battams said.

"That's the sign of a great mission — when right off the bat, you're getting answers to all of these questions that you had," he said during today's press conference. "But one of the truly remarkable things about the Parker mission is that it's also giving us answers to questions that we weren't even asking."

- NASA's Parker Solar Probe Sun Mission Explained (Infographic)

- Solar Quiz: How Well Do You Know Our Sun?

- Launch Photos! NASA's Parker Solar Probe Blasts Off to Touch the Sun

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.