When NASA's Parker Solar Probe flew close by the sun, telescopes were watching from Earth and space

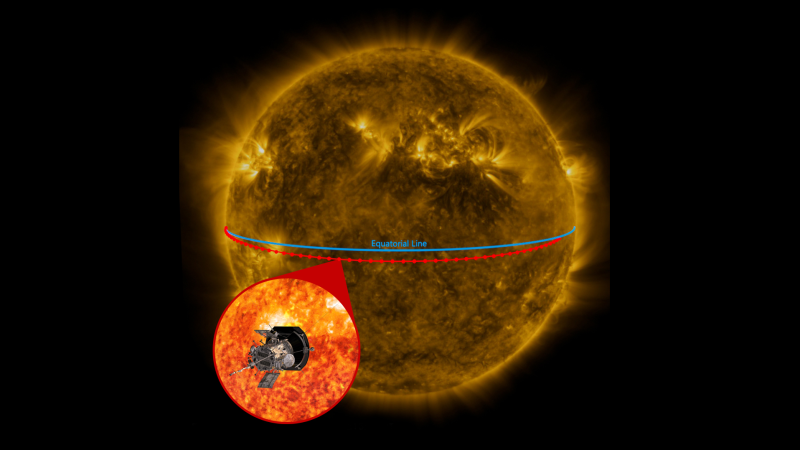

The spacecraft got close to 5 million miles from the sun's surface on Feb. 25.

Telescopes on Earth and in space had the sun safely in their sights when NASA's Parker Solar Probe made its 11th daring close flyby of the star on Feb. 25, all to understand more about the sun's behavior.

To be clear, the Parker Solar Probe wasn't directly visible in the various instruments, as the van-sized spacecraft was too small for the telescopes to pick out. But what the long-distance view did provide is valuable context for what the spacecraft saw close up, from as close as 5.3 million miles (8.5 million kilometers) from the sun's surface, Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUAPL) said in a statement.

The list of 40 observatories is literally globe-spanning, including the recently commissioned Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope in Hawaii, and other major telescopes in the United States, Europe and Asia.

Additionally, a dozen spacecraft provided viewpoints from around the solar system. NASA tasked its Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO), Solar Dynamics Observatory, Thermosphere Ionosphere. Mesosphere Energetics and Dynamics (TIMED) and Magnetospheric Multiscale missions.

Other contributions came from NASA's and the European Space Agency's Solar Orbiter, ESA's BepiColombo at Mercury, the Japanese-led Hinode solar observatory, and NASA's Mars Atmospheric and Volatile EvolutioN (MAVEN) at Mars.

Related: What's inside the sun? A star tour from the inside out

JHUAPL said it will take several weeks at the least to receive preliminary data, meaning that the analysis will take several more months or longer. "The team will get a glimpse of some readings when [Parker] sends a limited amount of data this week," the laboratory noted of its own mission.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Parker is trying to understand the mechanisms behind space weather, or the behavior from our sun in the form of events such as charged particle eruptions. Occasionally these eruptions can disrupt infrastructure such as power lines or satellites, or create colorful displays high in the atmosphere called auroras.

Scientists are also eager to see Parker's viewpoint when it recorded a large solar prominence on Feb. 15 that safely smacked the spacecraft, marking the largest such event the spacecraft experienced since it launched 3.5 years ago.

"The shock from the event hit Parker Solar Probe head-on, but the spacecraft was built to withstand activity just like this — to get data in the most extreme conditions," project scientist Nour Raouafi said in a statement. Pointing to the sun's 11-year-cycle starting to ramp up, Raouafi added the team "can't wait to see the data that Parker Solar Probe gathers as it gets closer and closer."

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.