NASA's Parker Solar Probe has touched the sun in daring mission milestone

In the superheated corona, the spacecraft was "flying into the eye of a storm," NASA says

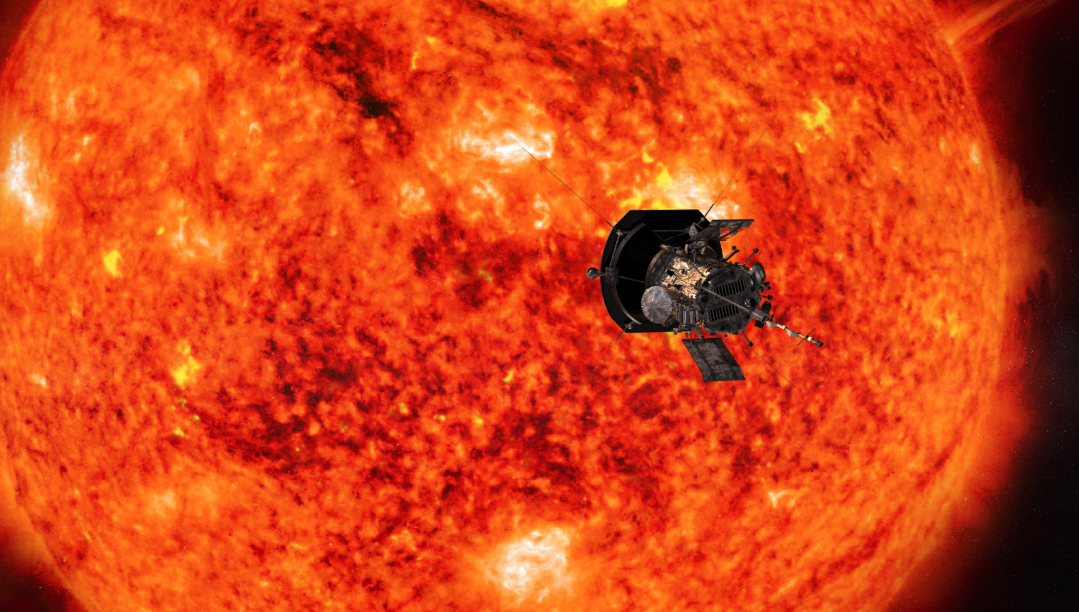

The Parker Solar Probe has finally reached the atmosphere of the sun.

The NASA spacecraft spent more than three years winding its way by planets and creeping gradually closer to our star to learn more about the origin of the solar wind, which pushes charged particles across the solar system.

Since solar activity has a large effect on living on Earth, from generating auroras to threatening infrastructure like satellites, scientists want to know more about how the sun operates to better make predictions about space weather.

Related: What's inside the sun? A star tour from the inside out

Observations from Parker's April 28 flyby, which was the eighth time the spacecraft whizzed by the sun, show that the spacecraft managed to get inside the sun's atmosphere, or the corona, for the first time. The results generated two science papers that NASA explored in a recent statement.

"We were fully expecting that, sooner or later, we would encounter the corona for at least a short duration of time," Justin Kasper, lead author on a new paper about the coronal milestone published in Physical Review Letters, said in the statement. Kasper is also deputy chief technology officer at BWX Technologies and a University of Michigan professor.

The sun isn't a solid sphere like our Earth, but it does have a zone in which the immense gravity of the star keeps in the solar material it spews through fusion.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

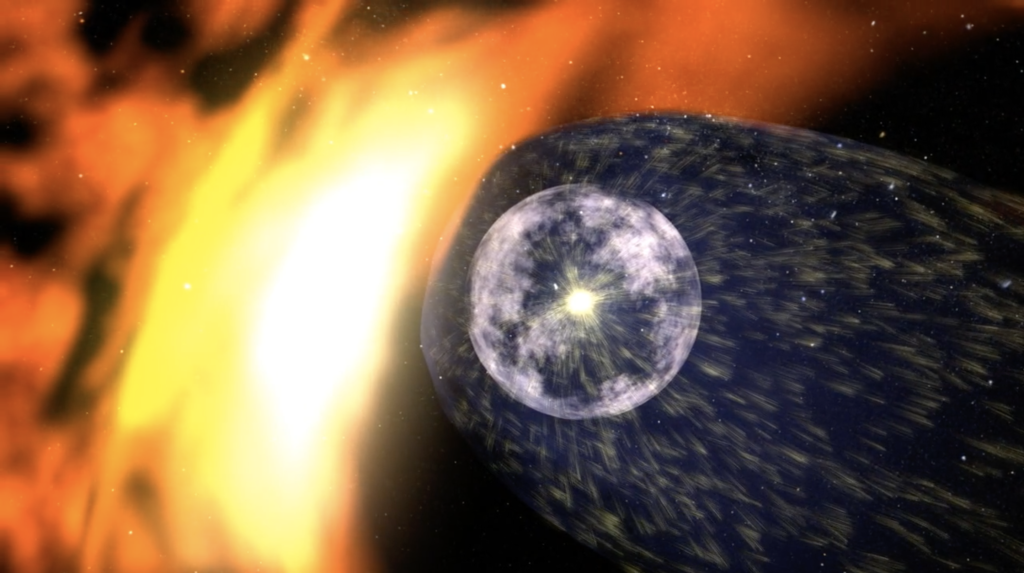

At a particular distance from the sun, however, gravity and magnetic fields are no longer able to keep that material close. It's from that point where the solar wind flows away from the sun, never to return. The point of no return is called the Alfvén critical surface and scientists had not been able to measure exactly where it was, before Parker reached it.

Previously, faraway pictures of the corona suggested that the critical surface was somewhere between 4.3 to 8.6 million miles (6.9 to 13.8 million kilometers) from the surface of the sun, or in relative terms, the equivalent of 10 to 20 times the radius of the sun. As it turns out, these estimates were not too far off. Parker's data suggests it crossed the critical surface at 18.8 solar radii, or 8.1 million miles (13 million km) above the sun's surface.

More importantly, Parker found the critical surface is not uniform, and there are "spikes and valleys" (as NASA termed it) in which the surface protrudes higher or lower from the center of the sun. The surface also likely varies with solar wind activity, which in turn depends on the sun's 11-year solar cycle.

"Discovering where these protrusions line up with solar activity coming from the surface can help scientists learn how events on the sun affect the atmosphere and solar wind," NASA officials wrote in the statement.

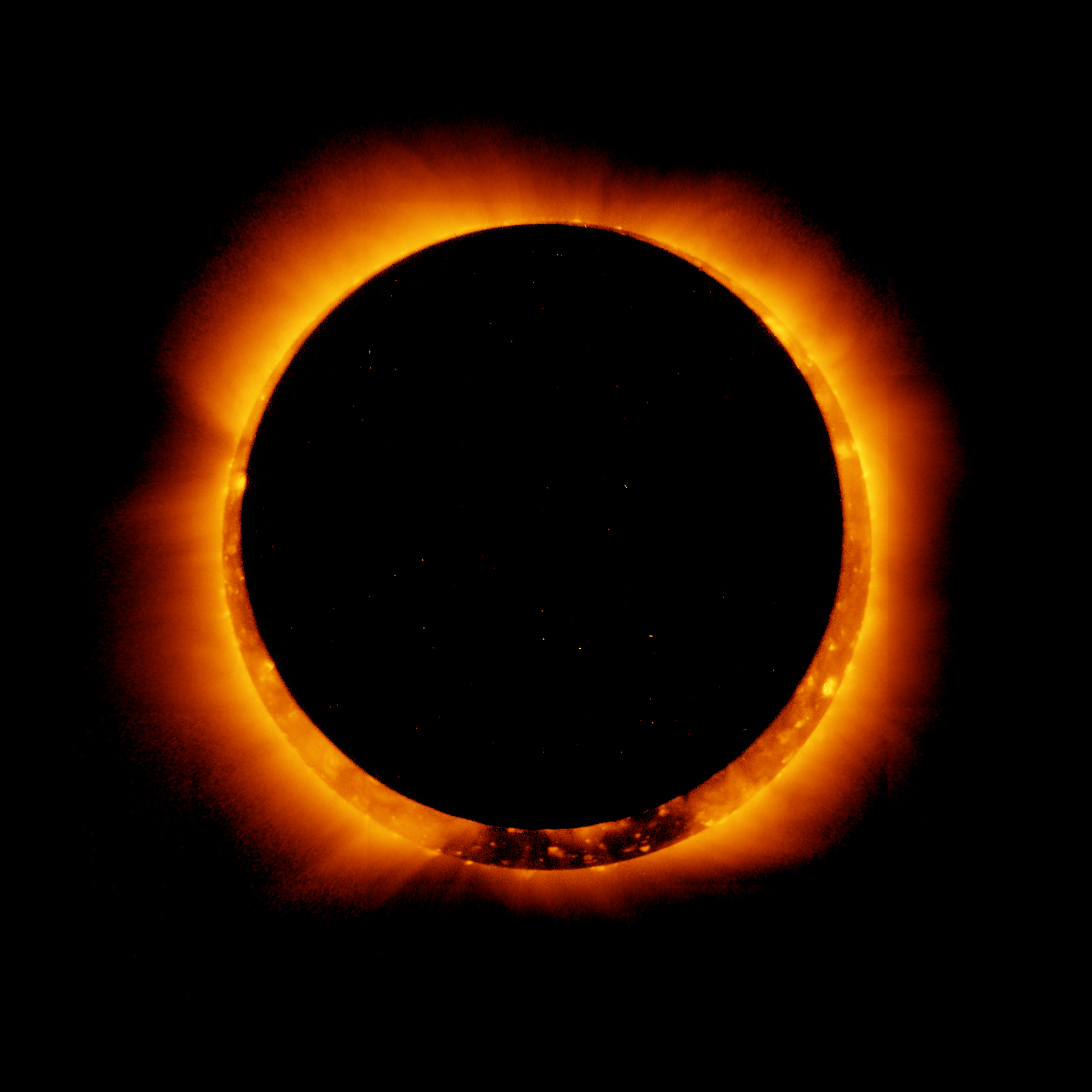

Parker could only spend a few hours in the corona due to the intense conditions there, but it did manage to go as low as 15 solar radii from the sun's surface. In that zone, it found a "pseudostreamer," one of the huge structures you can see from Earth during total solar eclipses.

"Passing through the pseudostreamer was like flying into the eye of a storm," NASA said in the same statement, noting that Parker saw changes such as quieter conditions and fewer particles.

On future flybys, Parker is expected to creep even closer to the sun, coming as low as 8.86 solar radii (3.83 million miles or 6.16 million km) from the sun's photosphere, its visible surface.

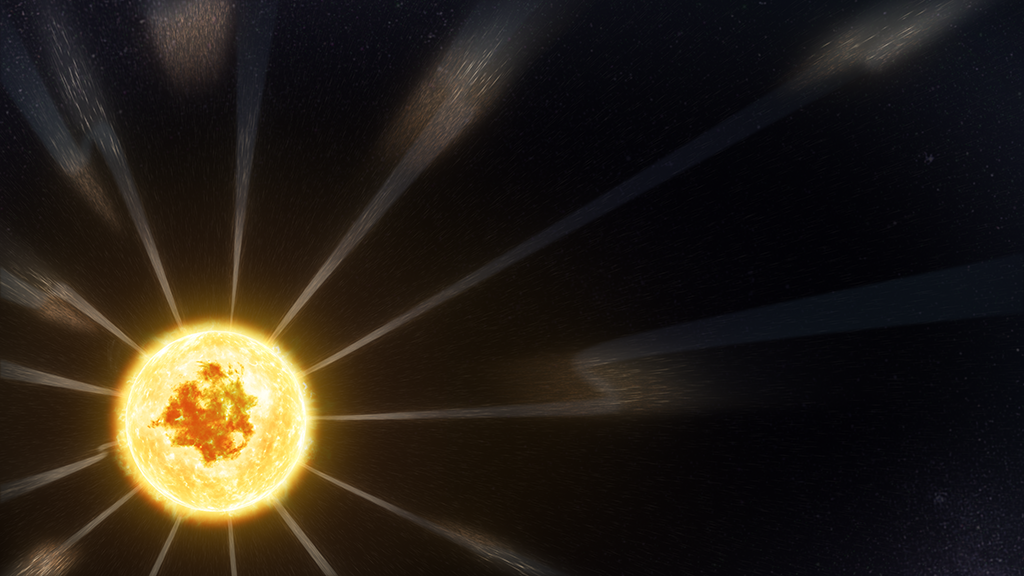

Farther away from the sun, the spacecraft has been exploring the physics of "switchbacks," or zig-zag-shaped structures in the solar wind.

Parker's work on this aspect of solar physics, now in press at the Astrophysical Journal, suggests that switchbacks originate at the visible surface of the sun, known as the photosphere. The switchbacks have been known for some time and were first discovered by the NASA-European Space Agency mission Ulysses, which orbited the sun's poles in the 1990s.

While scientists at first assumed the switchbacks were confined to solar regions, Parker found the switchbacks were quite common in the solar wind in 2019. Now fresh findings, from the mission's sixth solar flyby, suggest that switchbacks "occur in patches and have a higher percentage of helium" than other elements, NASA said.

Scientists also found that the patches line up with magnetic funnels coming from the photosphere, called supergranules. This is helpful to understanding solar physics because the funnels may be where fast particles of the solar wind originate.

"The structure of the regions with switchbacks matches up with a small magnetic funnel structure at the base of the corona," Stuart Bale, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and lead author on the new switchbacks paper, said in the NASA statement. "This is what we expect from some theories, and this pinpoints a source for the solar wind itself."

If scientists could better understand the physics of switchbacks, this may also point to why the corona is millions of degrees Fahrenheit or Celsius, which is far above the temperature of the solar surface.

"While the new findings locate where switchbacks are made, the scientists can't yet confirm how they're formed," NASA added. "One theory suggests they might be created by waves of plasma that roll through the region like ocean surf. Another contends they're made by an explosive process known as magnetic reconnection, which is thought to occur at the boundaries where the magnetic funnels come together."

Parker Solar Probe's next solar flyby is scheduled for late February 2022, although the spacecraft will gather observations for weeks before and after the closest approach.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.