If there ever was a planet that I feel has gotten a bad rap for its inability to be readily observed, it would have to be Mercury, known in many circles as the "elusive planet."

In the classic astronomy guide "New Handbook of the Heavens" (1941 McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc.), here is what is written about the innermost planet:

"Because you must look for it so soon after sunset, or before sunrise, Mercury stays close to the sun like a child clinging to its mother's apron strings. There was a famous astronomer, Copernicus, who never saw the planet all his life."

Related: Photos of Mercury from NASA's Messenger Spacecraft

Nonetheless, over the next three weeks, we will be presented with an excellent opportunity to view Mercury in the early morning/dawn sky. The planet is considered "inferior" because its orbit is nearer to the sun than the Earth's is: Therefore, Mercury always appears, from our vantage point, to be in the same general direction as the sun.

In old Roman legends, Mercury was the swift-footed messenger of the gods. The planet is well named, for it is the closest planet to the sun and the swiftest planet in the solar system, averaging about 30 miles per second (48 kilometers per second). Mercury makes its yearly journey around the sun in only 88 Earth days. Interestingly, the time it takes Mercury to rotate once on its axis is 59 days, so all parts of its surface experience periods of intense heat and extreme cold. Although the planet's mean distance from the sun is only 36 million miles (58 million km), Mercury has by far the broadest range of temperatures: 800 degrees Fahrenheit (427 degrees Celsius) on its day side; minus 280 degrees F (–173 degrees C) on its night side.

In the pre-Christian era, Mercury actually had two names; it was not known that it could alternately appear on one side of the sun and then the other. The planet was called Mercury when in the evening sky, but was known as Apollo when it appeared in the morning. There are reports that, around the 5th century B.C., Pythagoras pointed out that the two orbs were one and the same.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Sunrise ... sunset

Mercury possesses the most eccentric orbit of any planet. At its farthest distance from the sun (aphelion), the planet lies about 43 million miles (69 million km) away, but when it arrives at its closest point to the sun (perihelion) it's just less than 29 million miles (47 million km) away. So, its angular velocity through space is appreciably higher at perihelion. Interestingly, Mercury rotates on its axis three times for every two revolutions it makes around the sun. But when it arrives at perihelion (as it will on Aug. 20) Mercury's orbital velocity will exceed its rotational speed.

As a consequence, a hypothetical observer standing on Mercury would see a sight unique in our entire solar system: Over the course of eight days (four days before perihelion through four days after perihelion), the sun will appear to reverse its course, then double back and resume its normal track across the sky. If our observer were located on the part of Mercury where the sun rises around the time of perihelion, the sun would appear to partially come up above the eastern horizon, pause and then drop back below the horizon, followed in rapid succession by a second sunrise!

Mercury in the morning

Mercury rises before the sun all of this month, and is surprisingly easy to see from now through Aug. 27. All you have to do is just look low above the east-northeast horizon during morning twilight, from about 30 to 45 minutes before sunrise for a bright yellowish-orange "star."

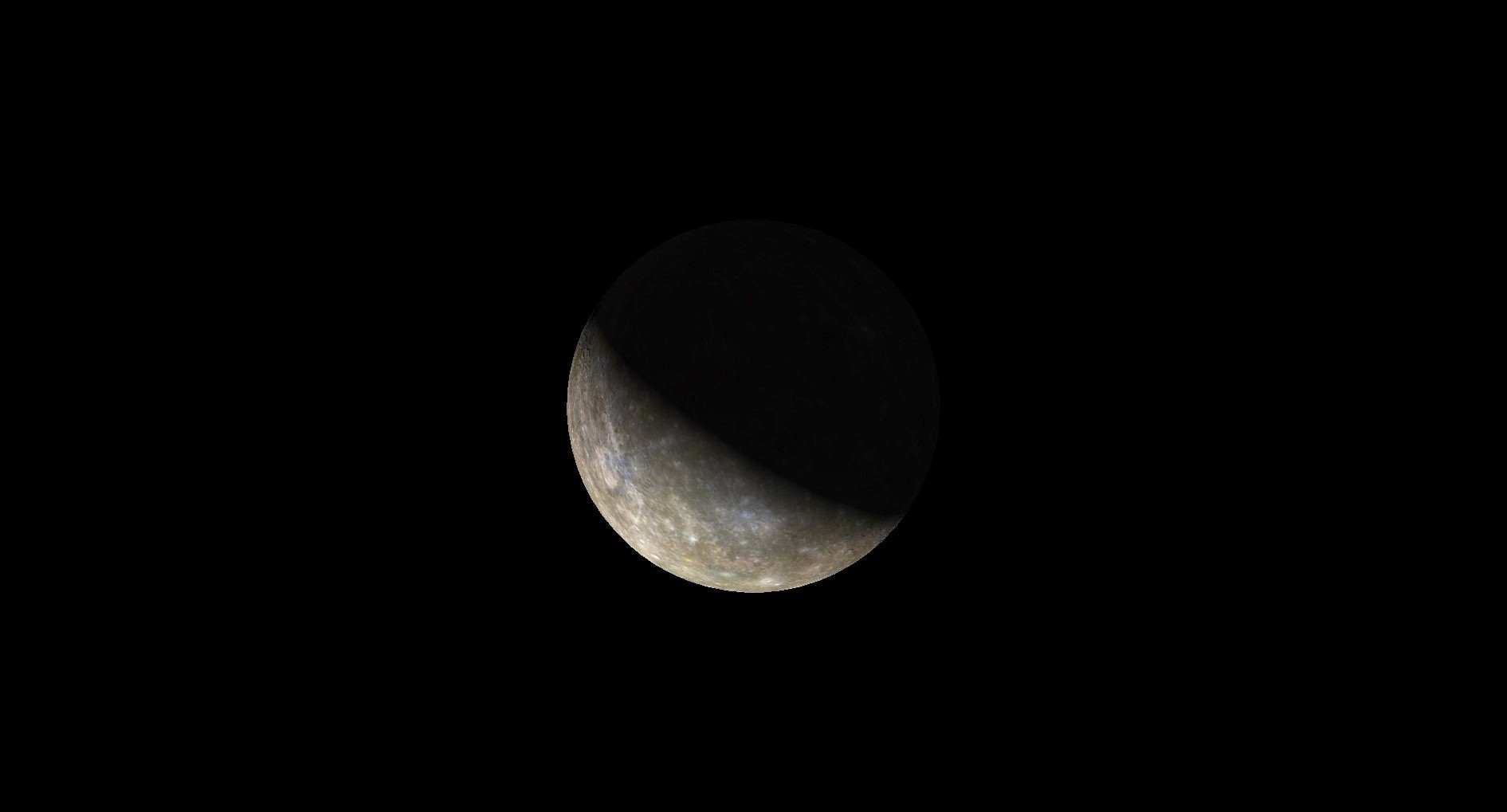

Mercury will be at its western elongation, 18 degrees to the west of the sun, on Aug. 9, rising shortly after dawn breaks and making this a very good morning apparition. Mercury, like Venus, appears to go through phases, like the moon does. When August began, Mercury was a crescent, just 13% illuminated by the sun. By next Tuesday (Aug. 6) that amount of illumination will have more than doubled to 28%, and the amount of its surface illuminated by the sun will continue to increase for the rest of this month: Almost 50% by Aug. 12 and more than 75% by Aug. 19. So, although the planet will begin to turn back toward the sun's vicinity after Aug. 9, Mercury will continue to brighten steadily, which should help to keep it in easy view over the next few weeks.

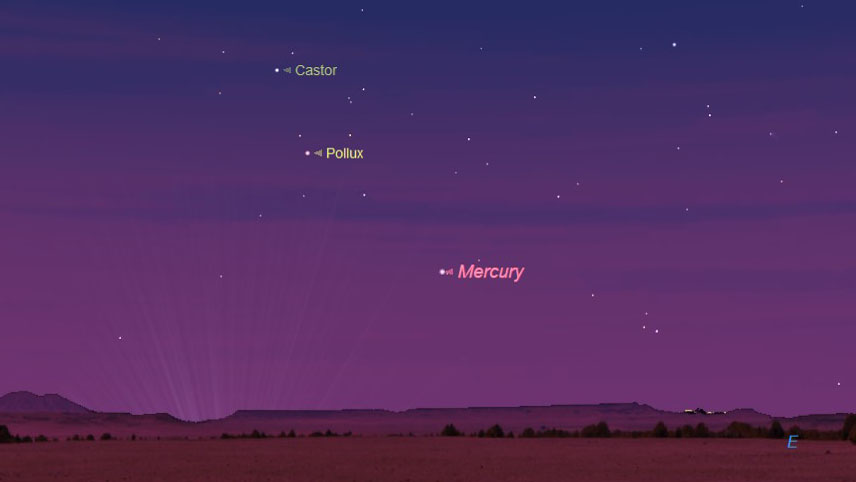

The 'Twins' point the way

As an added bonus, during the first half of August, Mercury will not be very far from the famous "Twin Stars" of the Gemini constellation, Pollux and Castor. These two stars will rise above the east-northeast horizon around 4 a.m. local daylight time, about half an hour before Mercury does The pair can be used as pointers to help you to locate Mercury.

During the first week of August, look for the Gemini twins at around 5 a.m. hovering about 15 degrees above the east-northeast horizon. Your clenched fist held at arm's length measures roughly 10 degrees, so Pollux and Castor will appear a bit higher than that above the horizon. Now look well down to the lower right of these stars and you'll see a somewhat brighter star-like object, hovering only about 5 degrees above the horizon.

That will be Mercury.

On Aug. 12, trace an imaginary line from Castor, through Pollux, continue straight toward the horizon for 10 degrees and you will come to Mercury, shining at a brilliant -0.3 magnitude. In the days that follow, the distance between Mercury and the Twin Stars will increase, while Mercury moves to their lower left.

The speedy planet will still be easily visible as late as Aug. 27; though nearer to the sun, it will have brightened to –1.5, even rivaling Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky. Thereafter, it drops back down under the dawn horizon.

- The Brightest Visible Planets in August's Night Sky: How to See them (and When)

- Catch a Shooting Star with 2019's Summer Meteor Showers

- The Mercury Transit of 2016 in Amazing Photos

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Verizon FiOS1 News in New York's lower Hudson Valley. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.