In Pluto's Realm, Small Objects Are Rare

Pluto's distant realm is a haven for pristine, primordial relics of the early solar system, a new study suggests.

Researchers have noted a distinct dearth of small craters on Pluto and its largest moon, Charon, indicating that fewer bantam bodies zoom through the Kuiper Belt — the ring of frigid bodies beyond Neptune — than previously thought.

This information, in turn, implies that collisions are rare way out there and that most Kuiper Belt objects (KBOs) have avoided significant disruption over the eons, study team members said.

Related: Destination Pluto: NASA's New Horizons Mission in Pictures

The researchers — led by Kelsi Singer of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado — studied photos captured by NASA's New Horizons spacecraft during its epic July 2015 flyby of Pluto.

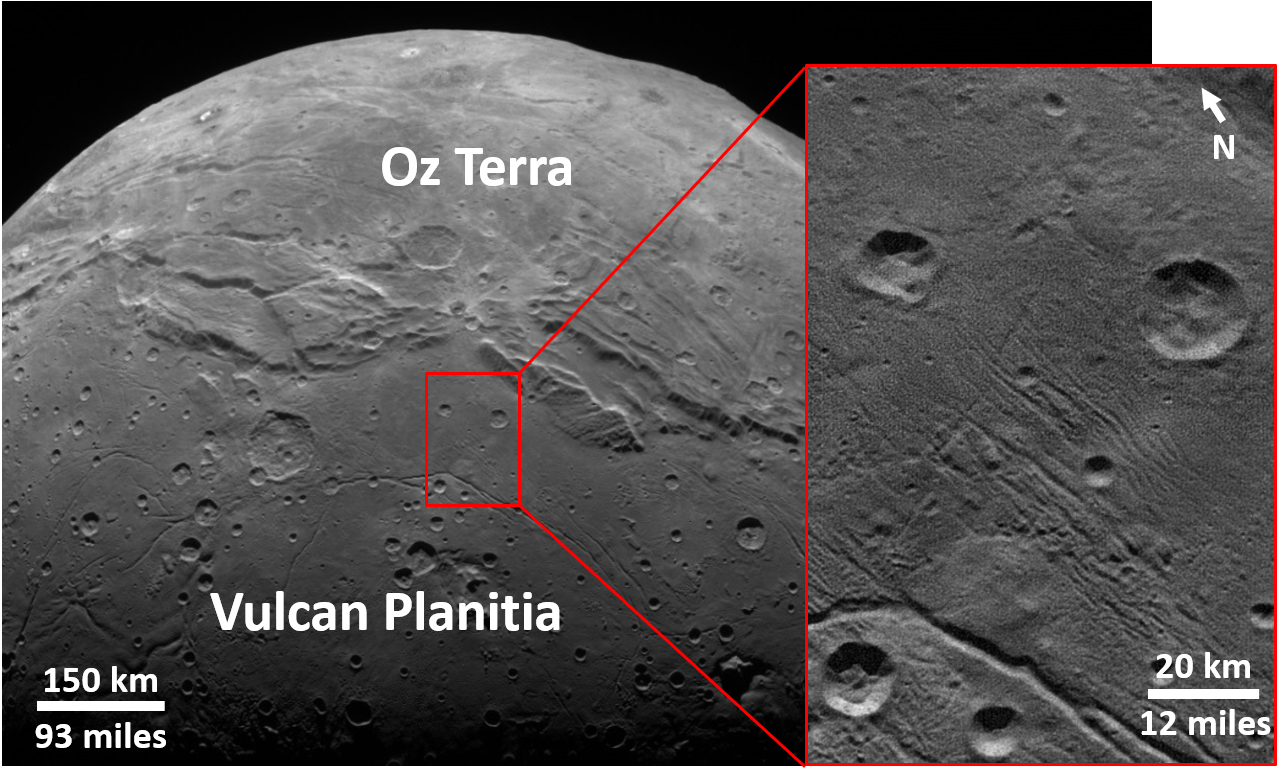

They counted and characterized craters on the dwarf planet and Charon, focusing especially on a smooth, ancient Charon plain known as Vulcan Planitia. There, impact features are highly visible and apparently well-preserved over long timespans.

Crater size is, of course, tied to impactor size, so the team was able to map out a size-frequency distribution for small KBOs — bodies too faint to be seen by telescopes here on Earth or in Earth orbit.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It's impossible to get this information without sending a probe to the outer solar system," Singer, a member of the New Horizons science team, told Space.com.

She and her colleagues found surprisingly few craters less than 8 miles (13 kilometers) wide, suggesting a pronounced scarcity of KBOs in the 0.6-mile to 1.2-mile (1 to 2 km) size range.

Such a scarcity is also implied by the paucity of small impact features on Ultima Thule, the 21-mile-wide (34 km) object that New Horizons zoomed past on Jan. 1. This second flyby for the craft, the most distant planetary encounter in spaceflight history, is the centerpiece of New Horizons' extended mission, which runs through 2021.

These twin results are at odds with models based on the situation in the inner solar system. Small bodies are relatively common in Earth's neck of the woods. Astronomers see some of these pipsqueaks in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, and Earth's moon preserves numerous craters blasted out by small impactors.

But it's becoming more and more apparent that the Kuiper Belt is quite different than the asteroid belt, Singer said. It therefore shouldn't be too surprising if the Kuiper Belt population is not in "collisional equilibrium" as objects in the asteroid belt appear to be and is instead dominated by celestial time capsules that scientists can probe to learn about the solar system's early days.

Still, Singer — and many other researchers — would love to get an up-close look at another KBO to help flesh out our nascent understanding of this dark and mysterious region.

"To see any other surfaces in the Kuiper Belt would be amazing," Singer said.

New Horizons could actually make this happen. The spacecraft is in good health and has enough fuel to perform a flyby of a third object if NASA grants another mission extension, team members have said.

The new paper was published online today (Feb. 1) in the journal Science.

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.