Dozens of starless 'rogue' alien planets possibly spotted

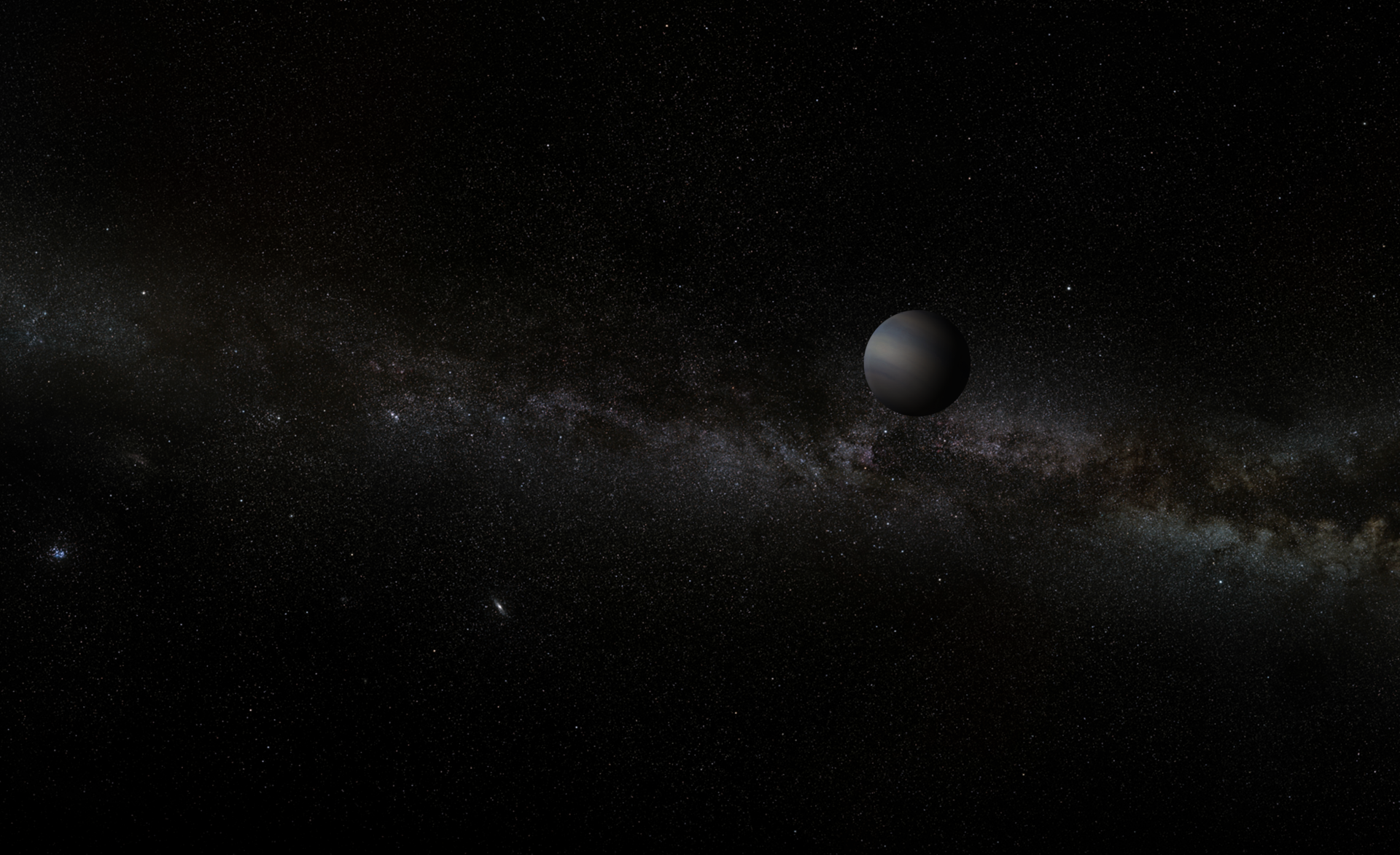

Astronomers have spotted more strange "free-floating" planets that could roam deep space untethered to any star.

While we might think that planets must need to orbit some kind of star, astronomers have detected such orphaned "rogues" before. And a new study uses data collected by NASA's planet-hunting Kepler space telescope to identify other possible exoplanets roaming freely on their own.

"Kepler has achieved what it was never designed to do, in providing further tentative evidence for the existence of a population of Earth-mass, free-floating planets," co-author Eamonn Kerins, a researcher at the University of Manchester in the U.K., said in a statement.

Related: Kepler's 7 greatest exoplanet discoveries

In the study, which was published July 6 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, the team used data that Kepler collected during a two-month stint in 2016 during the space telescope's K2 mission phase.

During this two-month period, Kepler observed a field of millions of stars near the center of our galaxy every 30 minutes. In analyzing this data, the team hoped to see signs of rare gravitational microlensing events, which occur when the gravity of a massive foreground object bends the light of a more-distant star or quasar, acting like a cosmic magnifying lens that allows scientists to see objects that might otherwise be too far to spot.

Over the course of the study, they found 27 short-duration signal candidates of varying lengths, from an hour all the way up to 10 days long.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Some of these signals had been seen previously in other data captured from the ground on Earth. However, the data from the four shortest of these microlensing events is consistent with the presence of planets with roughly the same mass as Earth.

If the microlensing events spotted with Kepler were to reveal a host star, or a star that has planets in its orbit, scientists might expect a longer signal. So, by finding evidence for these planets but without the longer signal typically associated with a host star, the team suspects that the planets might be free-floating.

It's possible that if these are, in fact, rogue, starless planets, that they may have originally formed around a host star and were pulled away by a gravitational force by a more massive planet or object, according to the statement.

But spotting these signals was no easy feat, especially seeing as Kepler wasn't designed to detect planets using microlensing, and it wasn't designed to study such a crowded field of stars. (Kepler, which was decommissioned in November 2018 after nearly a decade of in-space work, hunted for planets using the "transit method," looking for stellar brightness dips caused when a planet crossed its host star's face.)

"These signals are extremely difficult to find," lead author Ian McDonald, a researcher at the University of Manchester, said in the same statement. "Our observations pointed an elderly, ailing telescope with blurred vision at one of the most densely crowded parts of the sky, where there are already thousands of bright stars that vary in brightness, and thousands of asteroids that skim across our field."

"From that cacophony, we try to extract tiny, characteristic brightenings caused by planets, and we only have one chance to see a signal before it's gone. It's about as easy as looking for the single blink of a firefly in the middle of a motorway, using only a handheld phone," McDonald said.

To do this, the team had to develop new techniques to analyze their data. However, while their results are impressive and exciting, they do not confirm the existence of these rogue planets on their own. Future observations with missions like NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope and possibly also the European Space Agency's Euclid mission, both of which will be able to spot signals of microlensing events, could be used to help confirm the existence of these strange planets, according to the statement.

Email Chelsea Gohd at cgohd@space.com or follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Chelsea “Foxanne” Gohd joined Space.com in 2018 and is now a Senior Writer, writing about everything from climate change to planetary science and human spaceflight in both articles and on-camera in videos. With a degree in Public Health and biological sciences, Chelsea has written and worked for institutions including the American Museum of Natural History, Scientific American, Discover Magazine Blog, Astronomy Magazine and Live Science. When not writing, editing or filming something space-y, Chelsea "Foxanne" Gohd is writing music and performing as Foxanne, even launching a song to space in 2021 with Inspiration4. You can follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd and @foxannemusic.