Rapidly spinning 'extreme' neutron star discovered by US Navy research intern

"It was exciting so early in my career to see a speculative project work out so successfully."

A rapidly spinning neutron star that sweeps beams of radiation across the universe like a cosmic lighthouse has been discovered by U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) Remote Sensing Division intern Amaris McCarver and a team of astronomers.

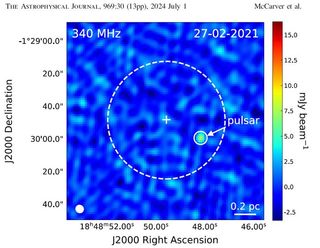

The rapidly spinning neutron star, or "pulsar," is located within the dense star cluster Glimpse-CO1, which sits in the galactic plane of the Milky Way around 10,700 light-years from Earth. This millisecond pulsar, which spins hundreds of times per second, is the first of its kind found in the Glimpse-CO1 star cluster. The Very Large Array (VLA) spotted the pulsar, which is designated GLIMPSE-C01A, on Feb. 27, 2021, but it remained buried in a vast amount of data until McCarver and colleagues found it in the summer of 2023.

Not only do the extreme conditions of these neutron stars make them the ideal laboratories to study physics in conditions found nowhere else in the universe, but their ultraprecise timing also means arrays of pulsars can be used as cosmic timepieces. These arrays are so precise that they can be used to measure the infinitesimally small squashing and squeezing caused as ripples in space and time called gravitational waves pass by. One possible practical application of this is the foundation of a "celestial GPS" that can be used for space navigation.

McCarver and her team found the object while investigating images from the VLA's Low-band Ionosphere and Transient Experiment (VLITE) to hunt for new pulsars in 97 star clusters.

Related: X-ray telescope catches 'spider pulsars' devouring stars like cosmic black widows (image)

"It was exciting so early in my career to see a speculative project work out so successfully," McCarver, one of 16 interns in the Radio, Infrared, Optical Sensors Branch at NRL DC, said in a statement.

The universe's dead stars

Like all neutron stars, millisecond pulsars are born when stars with masses greater than around eight times that of the sun reach the end of their lives. Once their fuel supplies needed for nuclear fusion has been exhausted, the outward energy that supports these stars against the inward push of their own gravitational pulls ceases.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This causes the cores of these stars to collapse and trigger shockwaves in the stars' outer layers, resulting in most of their masses being shed in massive supernova explosions.

The compressing stellar core crushes electrons and protons together, creating a sea of neutrons, which are neutral particles usually found locked in atomic nuclei alongside positively charged protons. This neutron-rich soup is so dense that if a tablespoon of it were brought to Earth, it would weigh over 1 billion tons. That's heavier than the largest mountain on our planet, Mount Everest (ironic, seeing as this pulsar was found under a mountain of data).

The creation of a neutron star with the mass of the sun crammed into a width of about 12 miles (20 kilometers) has other extreme consequences, too. Thanks to the conservation of angular momentum, the rapid reduction in the radius of a dead stellar core speeds up its rotation. This is the cosmic equivalent of an ice skater drawing in their arms to increase the speed of their spin, but on a whole different level that allows some neutron stars to reach rotational speeds as great as 700 turns per second.

Millisecond pulsars can also get a speed boost by stripping matter from a companion star close to it — like a cosmic vampire. This matter carries with it angular momentum as well.

The birth of a neutron star also forces magnetic field lines together, generating what are some of the most powerful magnetic fields in the universe.

These field lines channel charged particles to the poles of rapidly spinning pulsars, from where they are blasted out as jets. These jets are accompanied by beams of electromagnetic radiation that can periodically point at Earth as they sweep around with a pulsar's rotation. This is responsible for how the pulsar appears to brighten periodically. The name "pulsar" actually refers to the fact that, upon their initial discovery by Jocelyn Bell Burnell on Nov. 28, 1967, scientists thought these extreme dead stars were literally stars that pulsate.

After finding GLIMPSE-C01A in vast amounts of data from the VLA, the team confirmed its existence by reprocessing archival sky-survey data from the Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope.

"This research highlights how we can use measures of radio brightness at different frequencies to find new pulsars efficiently, and that available sky surveys combined with the mountain of VLITE data mean those measurements are essentially always available," Tracy E. Clarke, an astronomer with the NRL Remote Sensing Division, said in the statement. "This opens the door to a new era of searches for highly dispersed and highly accelerated pulsars."

"Millisecond pulsars offer a promising method for autonomously navigating spacecraft from low Earth orbit to interstellar space, independent of ground contact and GPS availability," Emil Polisensky, also an NRL Remote Sensing Division astronomer, added in the statement. "The confirmation of a new Millisecond pulsar identified by Amaris highlights the exciting potential for discovery with NRL’s VLITE data and the key role student interns play in cutting-edge research."

The team's research was detailed in a paper published on June 27 in The Astrophysical Journal.

Editor's Update 7/5: The newly discovered pulsar sits 10,700 light-years from us. This article has been updated to reflect that.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

-

Unclear Engineer Wow, only 10.7 light-years away is pretty close. Considering that the pulsar must be the result of a supernova, I wonder if we can date when it happened and determine what effects it may have had on Earth.Reply

I am somewhat surprised that it was not discovered sooner, considering its proximity to Earth. -

Jan Steinman Replytheir ultraprecise timing also means arrays of pulsars can be used as cosmic timepieces…

Elsewhere, I read that neutron stars randomly "glitch," which disturbs their precise timing, possibly due to "starquakes" or other disturbances.

How can a clock that randomly "glitches" truly be useful as a precision time piece? -

RobLea Not all pulsars glitch. Also scientists take a statistical average accross many pulsars to eliminate this. Also every measurement technique ever devised has a margin of errorReply -

Classical Motion Each one sings an unique tune(different radio color), that's why they are good spacial beacons.Reply

They will be fine for timing as long as they don't all glitch at the same time.

Using this kind of tech works both ways. It gives us advantage for navigation and backup.....and it verifies the location of those beacons. It won't be successful if not there. We'll get error.

Using this will probably allow us to fine tune those locations and possibly any change in them.

Is not application the ultimate study?

This is a great way to insure 24/7 monitoring of cosmological events and processes.