Strange radio emissions from a feeding star puzzle astronomers

Astronomers studying the fastest and most dramatic nova ever recorded continue to find more puzzles than answers.

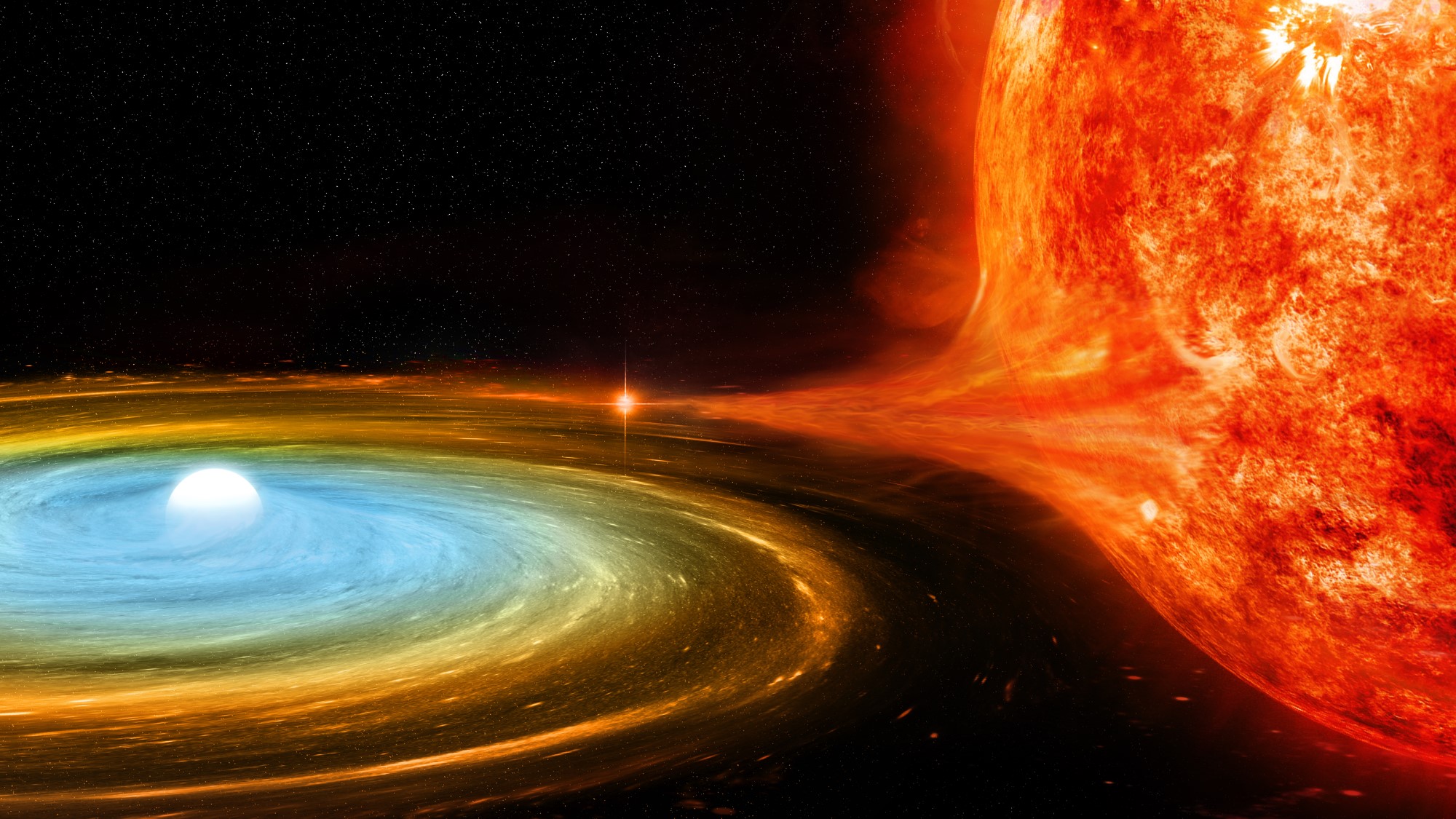

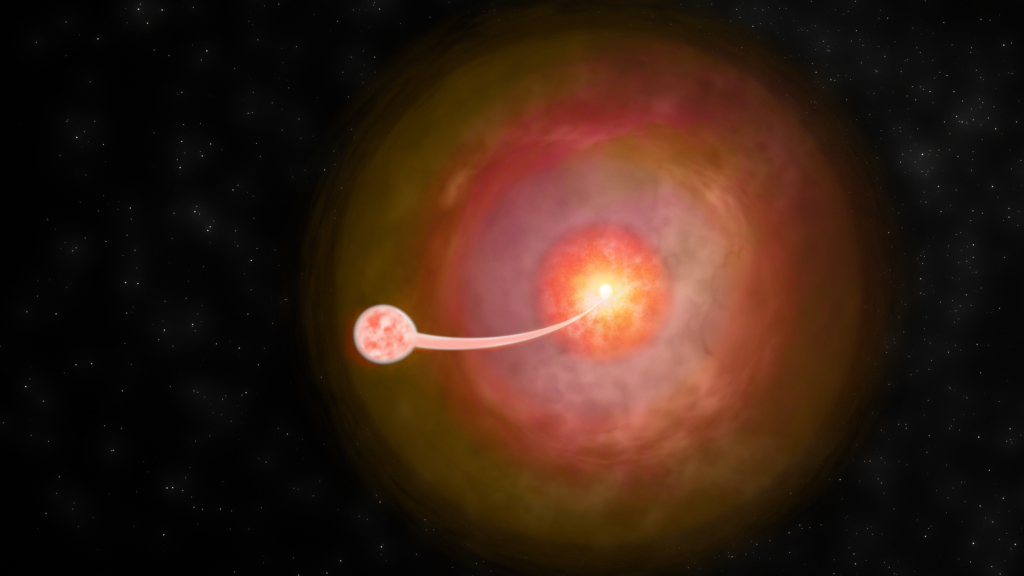

Novas are sudden, bright flares of light in a two-star system created when a white dwarf, the core of a dying star that has run out of fuel, steals material away from its companion star, causing the white dwarf to temporarily brighten. A nova known as V1674 Hercules found in a bizarre binary star system — made up of a white dwarf and a shredded companion in the Hercules constellation — has been the object of much interest since it first erupted two years ago on June 12, 2021. Astronomers were baffled by its light and energy, which rang like a bell, as well as its mysterious and intense winds that pumped stellar material into surrounding space.

Now, a team of researchers has spotted strange radio emissions sprouting from deep inside the V1674 Hercules nova that are very different from the high-temperature emissions normally seen during such events. "Right now, we're trying to determine if the non-thermal energy is coming from clumps of gas running into other clumped gas which produces shocks, or something else," Montana Williams, a graduate student at New Mexico Tech who is leading the new research, said in a statement.

Related: Fastest nova ever seen 'rings' like a bell thanks to feeding white dwarf

Wiliams revealed the strange emissions last week in a news briefing at the 242nd meeting of the American Astronomical Society being held in Albuquerque and online. Those emissions may be from interactions among chunks of stellar material ejected during the explosion, which is quite rare for "classical nova" such as V1674 Hercules, Williams said.

"Classical novas have historically been considered simple explosions, emitting mostly thermal energy," she added in the statement. "Instead, it seems they're a bit more complicated."

To study V1674 Hercules, Williams and her colleagues are using the Very Long Baseline Array, which is a network of ten antennas spanning the United States from Mauna Kea in Hawaii to Saint Croix in Virgin Islands. By combining those observations with similar data from other telescopes also watching the nova, including the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array telescope facility in New Mexico and the space-based Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (or NuSTAR), the team hopes to understand what's causing the mysterious radio emissions.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

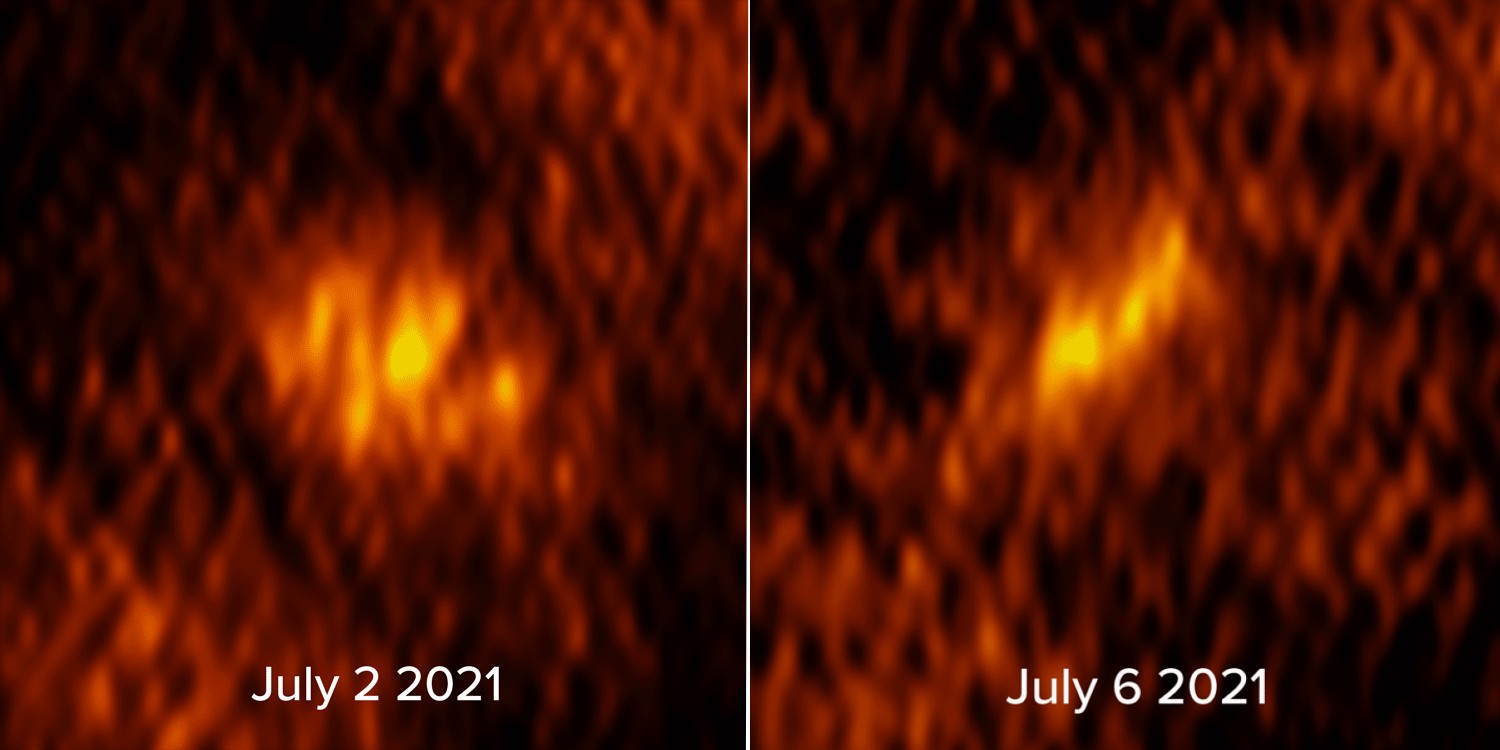

Researchers can measure how fast a nova evolves by observing how long the explosion takes to fade two magnitudes from its peak brightness. Extremely fast events take less than 10 days, moderate can ones take up to 80 days and the slow ones take anywhere from 80 to 150 days. The V1674 Hercules nova (or V1674 Her), whose flash of light was so bright that it could be seen with the unaided eye, took only 1.1 days to dim two magnitudes, or to about one-sixth of its original brightness.

"V1674 Her at 1.1 days is on an extreme end of an already extreme end, so it earns the title of the fastest nova," Williams said at the news conference last week.

A newly released pair of images by Williams and her team depicts just how drastic that pulsating change in brightness was between July 2, 2021 and July 6, 2021.

Unlike supernovas which completely destroy a star in violent explosions, classical novas such as V1674 Hercules leave the host stars intact and fully capable of putting on multiple shows, giving astronomers many opportunities to study how the system works.

In a broad brush, astronomers say studying the behavior and evolution of V1674 Hercules could also shed light on how galaxies evolve across eons, since the material that novas blast out into surrounding space is eventually recycled by nearby galaxies to feed the next generation of stars and planets.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social