Radio Telescope Unfurls 3 Antennas Beyond the Far Side of the Moon

In a quiet orbit around the far side of the moon, three radio antennas are now outstretched, craning for whispers from a mysterious period early in the universe's history.

The devices are attached to a Chinese communications satellite, Queqiao, which has been supporting the country's moon mission, Chang'e 4. As the equipment for an experiment dubbed the Netherlands-China Low Frequency Explorer, the antennas mark the first step toward ducking behind the moon in order to flee the eternal technological chatter of modern Earth that poses a constant challenge to radio astronomy.

"The mission came about during a visit of our king to China discussing cooperation in space," Heino Falcke, a radio astronomer at Radboud University in the Netherlands and a lead scientist on the experiment, told Space.com in August. "China, of course, wanted to go to the moon; we had proposed to put radio telescopes on the moon."

Related: Chang'e 4 in Pictures: China's Mission to the Moon's Far Side

The key to the collaboration was that China didn't just want to go to the moon — it wanted to go to the far side, a feat never accomplished previously. China's science priority was to better understand the differences between the two sides of the moon and what that could teach us about the moon's history.

But the far side of the moon is also the only place in the solar system where a massive amount of rock can shield instruments from the barrage of light waves produced by Earth's technology. Those long-wavelength radio signals constantly leak at Earth's surface and in orbit around our planet.

Frustratingly, the fingerprint of those signals happens to coincide precisely with a particularly intriguing signal that dates to a period after the Big Bang but before stars began to coalesce. "The Big Bang was gone, you had a boring, cold, dark universe filled with dark matter and hydrogen," Falcke said. "Essentially, it's this ocean of hydrogen. That's all. No stars, nothing."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

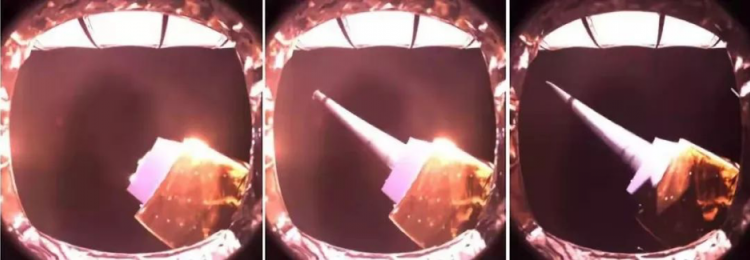

So for decades, radio astronomers have dreamed of rolling fine wires across the moon's far side to catch these signals and the birth of the first stars. The three antennas are hardly as ambitious as that, but their deployment on Nov. 27 marks a first step toward tackling such a challenge.

Related: Project Chang'e: China's Moon Missions Explained

The Netherlands-China Low Frequency Explorer launched in May 2018 on board China's Queqiao relay satellite, which it launched in preparation for the Chang'e 4 mission to the far side of the moon that arrived in January. Queqiao makes huge, lazy circles around what spacecraft engineers call the Lagrange 2 point, a spot directly behind the moon from Earth.

If Earth is a torso and the moon is a head, Queqiao traces out a halo wider than the girth of the moon above it, perpendicular to the line connecting the centers of the two spheres of rock. From that orbit, Queqiao can bounce signals between Earth and the two robots on the far side of the moon.

The arrangement means that the antennae aren't completely shielded from Earth's radio noise: a little sneaks around the edge of the moon. And hitching a ride on a communications satellite also makes for some radio chatter. "We bring our own interference source with us, and even though we're behind the moon we still see the Earth all the time now," Falcke said.

A key priority of the mission, then, will be to measure the interference itself, as well as trying to snag science data. The instrument was already gathering data for a few hours each lunar night while the surface robots slept, to understand the signals created by the spacecraft itself. Now, the team has both more time and the assistance (and interference, of course) of the antennae.

"Our contribution to the Chinese Chang'e 4 mission has now increased tremendously," Marc Klein Wolt, managing director of the Radboud Radio Lab and a leader of the project, said in a statement. "We have the opportunity to perform our observations during the 14-day-long night behind the moon, which is much longer than was originally the idea. The moon night is ours, now."

According to the statement, the antennae didn't unfurl quite as smoothly as the team had hoped, so mission personnel paused the operation to gather some data now. In the current configuration, the devices should be able to pick up signals from about 800 million years after the Big Bang, the statement noted. The deployment hiccup may be a consequence of the year and a half the instrument has already spent in the harsh environment of space.

The Netherlands-China Low Frequency Explorer was designed to work for three years, but half of that time was eaten up by delays deploying the antennas, when China didn't want to risk communications with the Chang'e 4 robots. The Queqiao spacecraft itself is designed to stay at work for 10 years, which could give the radio science experiment a longer tenure.

Falcke said that he hopes Queqiao's orbit may eventually be tweaked such that the instrument could at least temporarily duck within the quiet zone behind the moon, where it could gather cleaner data.

"This is, in a sense, pie in the sky right now," Falcke said. "We have no guarantee."

- Photos from the Moon's Far Side! China's Chang'e 4 Lunar Landing in Pictures

- NASA Probe Spots China's Chang'e 4 Lander on Far Side of the Moon (Photo)

- China's Chang'e 4 Returns First Images from Moon's Farside

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.