Rocket Lab doesn't want to be a Venus dilettante.

The California-based company aims to launch a private Venus mission in 2023 to hunt for signs of life in the clouds where scientists just spotted the possible biosignature gas phosphine. But that landmark effort will be just the beginning, if all goes according to plan.

"We don't want to do one mission — we want to do many, many missions there," Rocket Lab founder and CEO Peter Beck told Space.com Monday (Sept. 14), hours after scientists unveiled the Venus phosphine discovery.

Related: Venus' clouds join shortlist for potential signs of life in our solar system

A long-held dream

Beck has long wanted to help explore Venus, which he thinks has not yet received the scientific attention it deserves.

"Venus is well and truly undervalued," he said.

Venus was once a temperate world like Earth, with plentiful surface water — including, many scientists believe, large oceans that may have persisted for much of the planet's 4.5-billion-year history.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But a runaway greenhouse effect eventually took hold on the second rock from the sun, baking out Venus' water and transforming its surface into the scorched, high-pressure hellscape it is today. And "hellscape" really isn't an exaggeration: Surface temperatures on Venus hover around 872 degrees Fahrenheit (467 Celsius), hot enough to melt lead.

Learning exactly what happened to Venus, and why, is of great interest to planetary scientists. And the planet's evolution serves as a sort of cautionary tale for Earth, where human activity has ushered in a period of dramatic warming, Beck noted.

Then there's Venus' astrobiological potential, which may not be restricted to the ancient past. Though the planet's surface turned infernal, researchers think a pocket of potential habitability remained high in the clouds, about 30 miles (50 kilometers) up, and survived into the present day. Way up there, temperatures and pressures are quite similar to those found on Earth at sea level (though Venusian clouds are mostly made of sulfuric acid rather than water vapor).

That cloud layer is where a team of scientists recently spotted the fingerprint of phosphine, a gas that here on Earth is produced only by microbes and human activity, as far as we can tell. And it's the environment that Rocket Lab wants to probe with that 2023 mission and its hoped-for successors.

Related: Photos of Venus, the mysterious planet next door

The plan

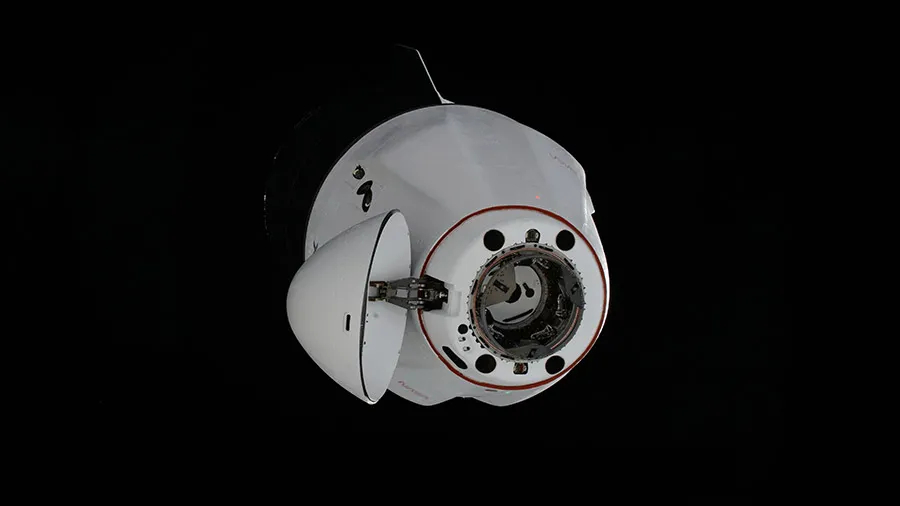

The coming Venus mission will employ two pieces of Rocket Lab hardware — the 57-foot-tall (17 meters) Electron booster, which has been launching small satellites to orbit since early 2018, and the Photon satellite bus, which made its spaceflight debut on an Electron mission late last month.

A Photon will launch atop an Electron, then make its way to Venus on a flyby trajectory. When the Photon gets close, it will deploy a probe into the Venusian atmosphere. This won't be the first Photon trip beyond Earth orbit, by the way; NASA has booked Electron and Photon to fly a small satellite to the moon in early 2021.

"The probe is targeted at kind of an entry angle that maximizes the amount of time in that 50-kilometer[-high] region of interest," Beck said. Though the Venus entry probe will be "coming in super-hot" at about 24,600 mph (39,600 km/h), "we do get a reasonable amount of time in that really interesting zone," he added.

The probe won't be balloon-borne, like the Soviet Venera missions that plied the Venusian skies in the 1980s. It will be more akin to the four small descent craft successfully deployed into the Venus atmosphere by NASA's Pioneer Venus Multiprobe mission in 1978, Beck said.

"We're taking a lot of inspiration from some of that probe design," he said.

The goal is to hunt for signs of life in the potentially habitable patch of Venus air. And Rocket Lab is already talking to scientists about the best ways to do this — including members of the team who spotted phosphine in the planet's clouds. (To be clear: This phosphine is a potential, not confirmed, sign of alien life. More work is needed to determine what processes are generating the gas.)

"We have been talking to them. And they're amazing, to be so flexible," MIT planetary scientist Sara Seager, one of the world's leading experts on biosignature gases, said during the phosphine announcement press conference on Monday.

Rocket Lab's entry probe will likely tip the scales at about 82 lbs. (37 kilograms), Beck said. About 6.6 lbs. (3 kg) of that would be devoted to scientific payload, according to Seager.

"So, you'd have to work hard to make sure an instrument that would be useful for the search for life will fit into that payload," Seager said. "And we're really looking forward to it."

Related: 6 most likely places for alien life in the solar system

An exploration campaign?

Rocket Lab's Venus plans were in the works long before the company started talking to Seager and her colleagues, Beck said. The phosphine detection didn't change much, apart from strengthening his resolve and boosting his optimism.

"I thought the probability of finding something interesting was incredibly low, whereas now I think that the probability of finding something interesting is much improved, given the phosphine," he said. "But even just to take an in situ measurement of the phosphine I think is hugely important scientifically."

Electron and Photon are pretty much set for the 2023 mission, Beck said, noting that Photon will prove its deep-space bona fides on the NASA moon mission next year. Most of the work that still needs to be done involves development of the atmospheric probe and its scientific instrumentation.

Beck is confident that Rocket Lab can get everything ready to go for a launch just three years from now. And that will be a major milestone — a private life-hunting mission, developed and launched in just a few years at a total cost of $10 million to $20 million.

Compare that to NASA's low-cost Discovery program of robotic space missions, which mandates a cost cap of $450 million, excluding launch. (Two of the four Discovery mission candidates in the most recent selection round would explore Venus, by the way. Neither is a life-hunting effort, although one of them, called DAVINCI+, would send a probe through the Venusian atmosphere.)

Rocket Lab is planning to pay the full tab for the 2023 mission. But Beck said he'd "love to do a bunch more" Venus missions and would certainly be open to collaborating with a variety of partners — a prospect that may get a big boost from the phosphine find.

"To be honest with you, Venus has always been something that, traditionally, it's relatively hard to get too many people excited about," Beck said.

"With this announcement, I'm certainly hoping that more focus and more energy goes on to Venus, which will create more opportunities for scientists and instrument developers to look more closely and carefully at what we want to do."

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.

-

Mergatroid If Venus is not inside the habitable zone of SOL, being too close to the Sun to harbor liquid water, why does everyone keep saying that "something happened that caused the water to disappear" when we know that it's too close to the Sun? How could it have had water oceans at this distance, and even if it did why would anyone expect those oceans not to disappear?Reply

Many times we are subjected to the history of Venus as if it's some kind of lesson to learn about Earth, but Earth was never that close to the Sun, and is indeed the only planet in our system in the habitable zone.

Add to this the lack of a magnetic field, which would cause the planet to be bombarded by the Solar wind, and it seems only natural that any water that may have been there at one time would be gone.

Could it be that Venus used to be farther out, and somehow had its orbit changed?

What I find amusing here really is that, with all the investment by governments around the world into space exploration, it could actually be a private company that discovers life outside our planet.