Pollution from rocket launches and burning satellites could cause the next environmental emergency

'If we don't take any action now or in the next five years, it might be too late.'

The growing number of rocket launches and satellites burning up in Earth's atmosphere could trigger the world's next big environmental emergency. Experts are racing to understand the new threat before it's too late.

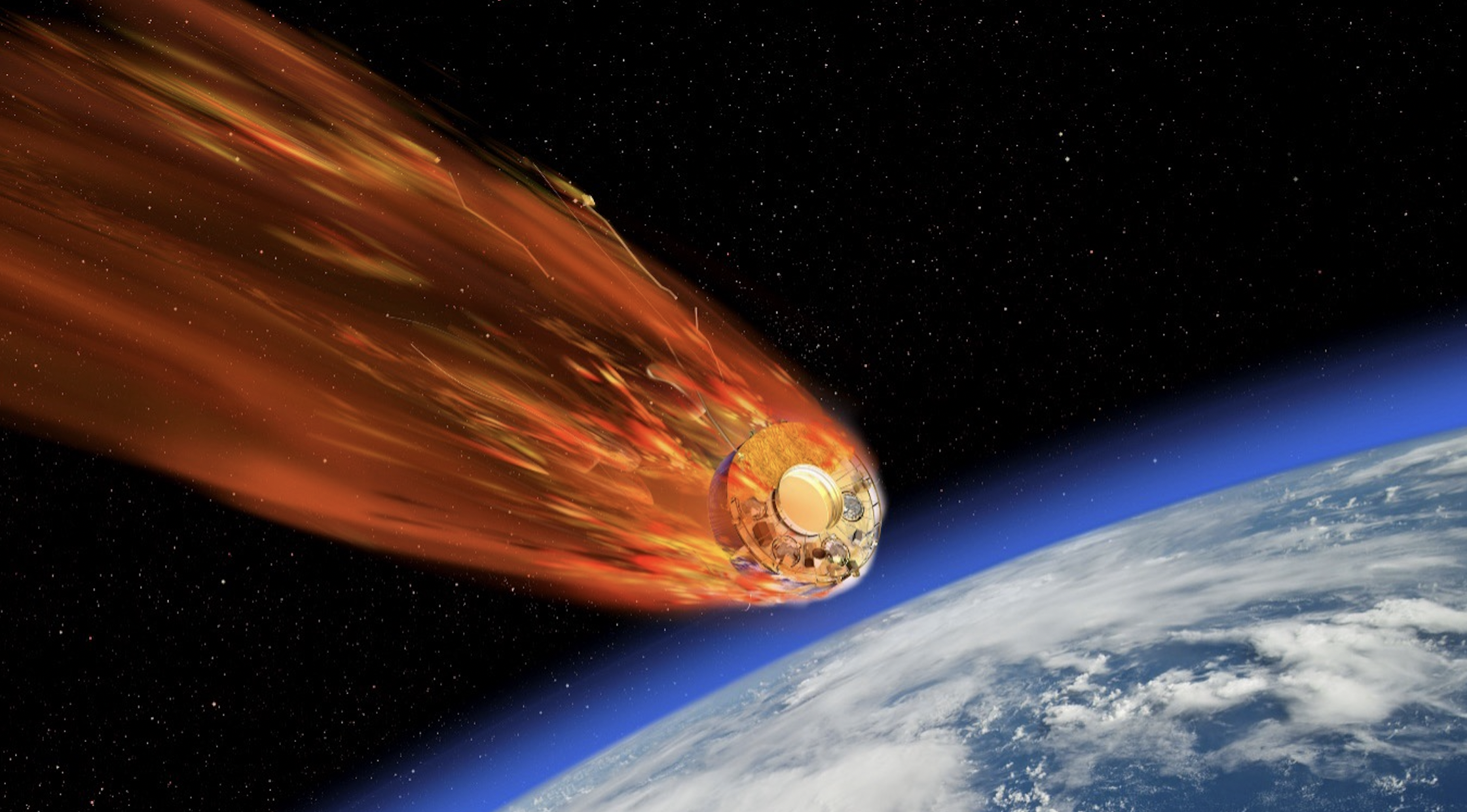

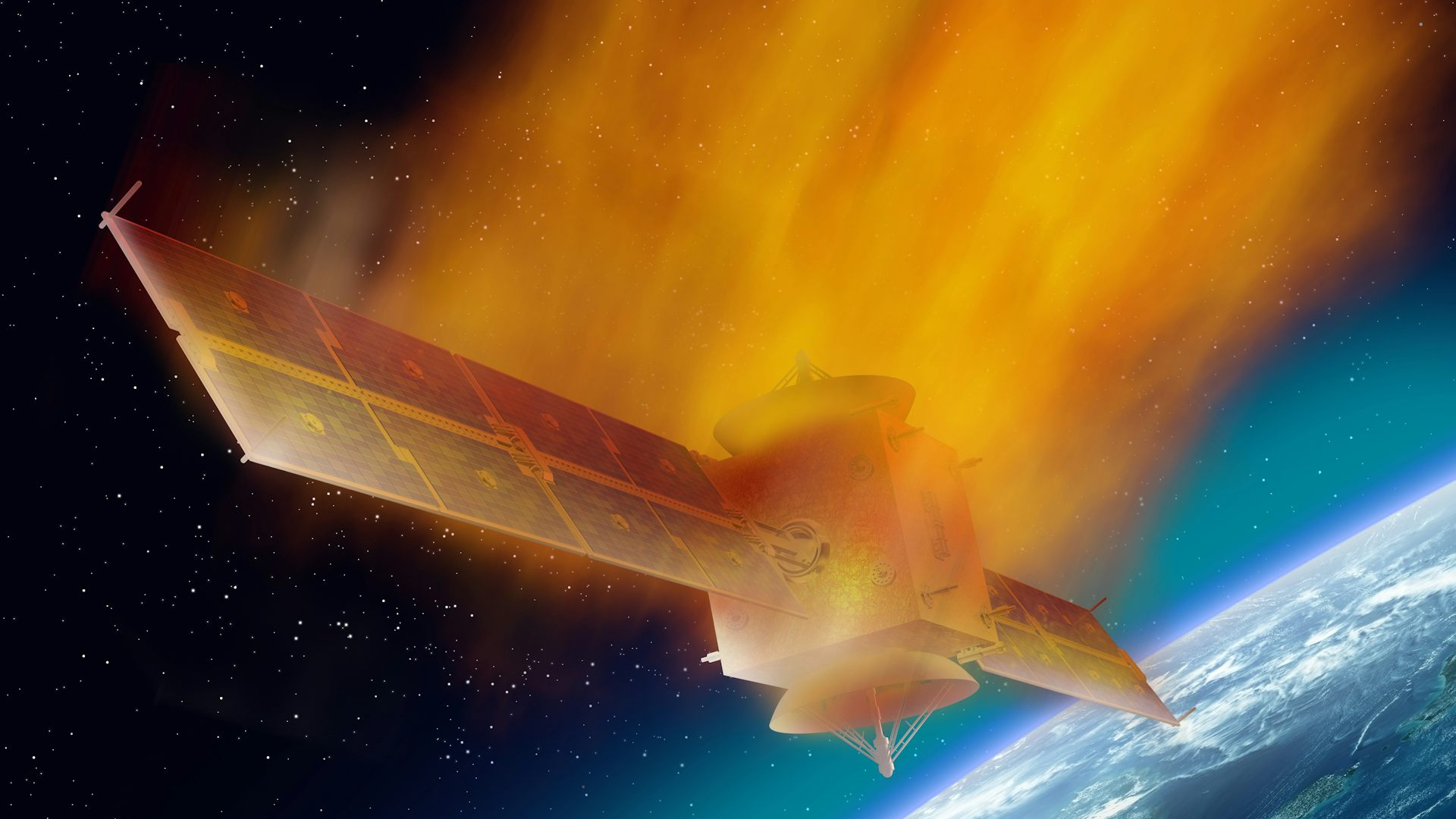

The space industry is booming. Over the past 15 years, the number of rockets launched per year has nearly tripled, and the number of satellites orbiting the planet has increased tenfold, according to Statista. The amount of space debris — old satellites and spent rocket stages — falling back to Earth has doubled over the past 10 years. A few hundred tons of old space junk now vaporizes in the atmosphere every year, experts say.

And all of this is just the beginning. Applications for satellite spectrum for 1 million satellites have been filed with the International Telecommunications Union, and, although not all of those plans are likely to come to fruition, experts expect that around 100,000 spacecraft may circle Earth by the end of this decade. The majority of those satellites will belong to one of the megaconstellation projects, such as SpaceX's Starlink, that are currently planned or being deployed. By that time, the amount of space junk burning up in the atmosphere on a yearly basis is expected to reach more than 3,300 tons (3,000 metric tons).

Soot and alumina

Most rockets in use today run on fossil fuels and release soot, which absorbs heat and could increase temperatures in the upper levels of Earth's atmosphere. The atmospheric incineration of satellites produces aluminum oxides, which too can alter the planet's thermal balance. Both types of emissions also have the potential to destroy ozone, the protective gas that keeps dangerous ultraviolet (UV) radiation from reaching Earth's surface, studies suggest.

Related: Burned-up space junk pollutes Earth's upper atmosphere, NASA planes find

A study published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters in June found that concentrations of aluminum oxides in the mesosphere and stratosphere — the two atmospheric layers above the lowest layer, the troposphere — could increase by 650% in the coming decades due to the rise in reentering space junk. Such an increase could cause "potentially significant" ozone depletion, the study concluded.

Another study, published a year earlier and authored by a team from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), concluded that the expected increase in soot-producing rocket launches will have a similar effect on ozone depletion.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Yet another NOAA study, presented at a conference of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics in Florida in January, found that the increase in concentrations of aluminum oxides in the stratosphere could produce "significant temperature anomalies" in the stratosphere.

Other researchers have suggested that the shroud of metallic ash that is forming in the stratosphere as a result of the satellite reentries may interfere with Earth's magnetic field. The satellite dust could weaken the magnetic field, the researchers think, possibly allowing more harmful cosmic radiation to reach the planet's surface.

High up in the atmosphere

Both rockets and reentering satellites inject air pollution into higher layers of the atmosphere, which are out of reach of ground-based polluters. Even aircraft emissions are contained within the troposphere. Rockets, on the other hand, emit their exhaust throughout their climb through the atmospheric column.

Sebastian Eastham, an aerospace sustainability researcher at Imperial College London, told Space.com that rocket air pollution, due to the high altitude at which it is emitted, is "untested territory."

"Our understanding of the consequences of an emission decreases the further you get from the surface," Eastham said.

The higher the altitude of the air pollution particles, the longer they will remain in the atmosphere and the more time they will have to wreak havoc. But how much more havoc this high-altitude air pollution wreaks is unknown as well, added Eastham.

Ash from reentering satellites also accumulates high above the planet. Most of a satellite's mass burns up between altitudes of 37 miles and 50 miles (60 to 80 kilometers), according to Minkwan Kim, associate professor of astronautics at the University of Southampton in the U.K. Kim leads an international project funded by the U.K. Space Agency that aims to evaluate the environmental threats presented by satellite reentries and propose solutions to the problem.

"If we put the small particles at a very high altitude, they're going to stay there a very long time," Kim told Space.com. "Probably 100 years, 200 years."

Kim and his colleagues think that satellite operators could reduce the time the dangerous particles remain suspended in the thin air of the upper atmosphere by controlling the reentry trajectory to make those satellites burn at lower altitudes.

"If we burn it at the low altitude, like 20, 30 kilometers [12 to 18 miles], this metal oxide that is generated will eventually drop to the ground," Kim said.

Research into atmospheric effects of rocket flights and satellite air pollution is still in its early stages, Kim noted. However, he stressed that the space industry doesn't have time to waste. With the expected growth in the number of both reentering satellites and rocket launches, the world could soon have another major environmental crisis on its hands.

"If we don't take any action now or in the next five years, it might be too late," said Kim. "Starting earlier would probably mean a better chance to prevent serious problems. Just like with CO2 emissions, if it happened earlier, we would have a better response to global warming."

Related: Climate change: Causes and effects

Calls for regulation

Air pollution from rocket flights and reentering satellites is currently not subject to any regulations, Kim added.

In the U.S., the nonprofit Public Interest Research Groups (PIRG) recently called on the Federal Communications Commission, which awards licenses to satellite operators, to halt all megaconstellation satellite launches until the environmental impacts of satellite reentries are assessed.

An exemption from the National Environmental Protection Act in place since 1986 means that the FCC doesn't have to carry out environmental impact reviews before awarding satellite licenses. But experts say that things have changed in the last 40 years, and the FCC needs to change its attitude to satellite pollution.

This novel environmental threat is also outside the scope of all existing international space and environmental protection treaties.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.