A rogue rocket is on course to crash into the moon. It won't be the first.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Alice Gorman, Associate Professor in Archaeology and Space Studies, Flinders University

In a few weeks' time, a rocket launched in 2015 is expected to crash into the moon. The fast-moving piece of space junk is the upper stage of a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, which hoisted the Deep Space Climate Observatory satellite off our planet. It has been chaotically looping around Earth and the moon ever since.

Asteroid-hunter Bill Gray has been keeping tabs on the 4-tonne booster since its launch. This month he realized his orbit-tracking software projected the booster will slam into the lunar surface on March 4, moving at more than 9,000 kilometers per hour.

The booster is tumbling wildly as it travels, which adds some uncertainty to the timing and location of the predicted impact. It is likely to occur on the far side of the moon, so it won’t be visible from Earth.

Related: SpaceX rocket stage on a collision course with the moon captured in telescope images

For those asking: yes, an old Falcon 9 second stage left in high orbit in 2015 is going to hit the moon on March 4. It's interesting, but not a big deal.January 25, 2022

Some astronomers say the collision is "not a big deal," but to a space archaeologist like me it's quite exciting. It will be the moon's newest archaeological site, joining more than 100 other locations that document human activity on the moon and in cislunar space.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A history of crash landing on the moon

The impact will leave a new crater on the dark side of the moon.

The very first human-made artifact to make contact with the moon was the Soviet Luna 2 in 1959 — an extraordinary feat, as it was only two years after the launch of Sputnik 1, the first artificial Earth satellite.

The mission consisted of a rocket, a probe, and three "bombs." One released a cloud of sodium gas to enable the crash to be seen from Earth. The USSR didn’t want the groundbreaking mission to be called a hoax.

The other two "bombs" were spheres of pentagonal medallions inscribed with the date and Soviet symbols. If they exploded as planned, they would have scattered 144 medallions over the lunar surface.

Read more: Tardigrades: We're now polluting the moon with near-indestructible little creatures

Other crashes have been missions gone wrong, like the Israeli Beresheet lander in 2019. This was especially controversial as the lander carried a secret cargo of dried tardigrades, tiny creatures that could be revived in the presence of water.

Various spacecraft have naturally decayed and fallen out of orbit, like the Japanese relay satellite Okina in 2009. Others have been intentionally crashed at the end of their mission life.

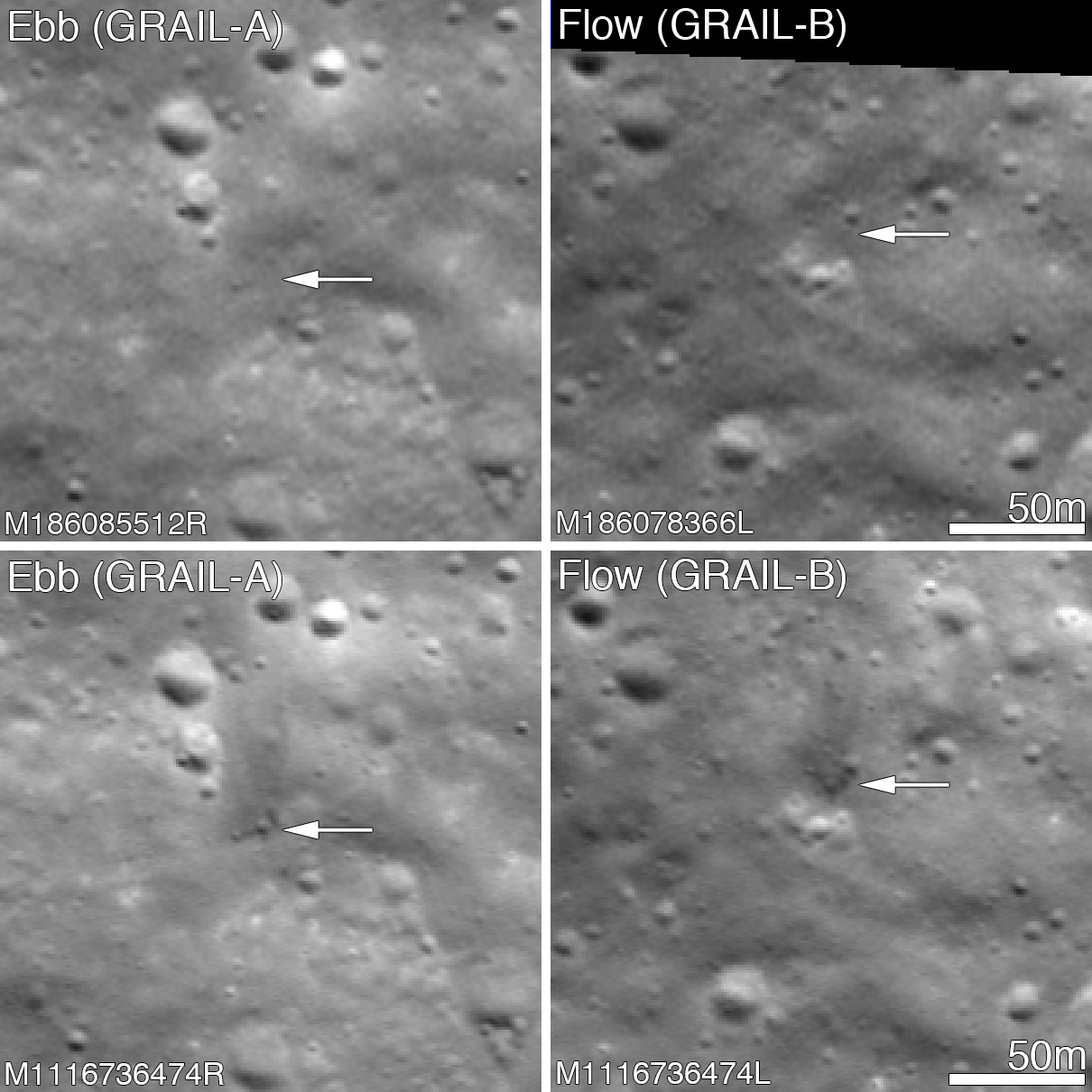

The NASA Ebb and Flow spacecraft were deliberately crashed into the lunar south pole in 2012, specifically to avoid any risk of damaging the Apollo landing sites. Impacting at a speed of 6,000km per hour, they left craters 6 meters across.

Many crashes have been used to collect seismic data. Observations from the controlled impact of Saturn third-stage boosters and ascent modules from the Apollo missions were particularly valuable, as timing, location and impact energy were known.

Environmental impacts

The Falcon 9 rocket stage is significantly larger than the tiny Ebb and Flow spacecraft and is traveling faster. The crash will make a much larger crater, which will kick up chunks of rock and dust. On this airless world, the dust could travel a fair way before settling down.

The only other spacecraft on the moon's far side are the US Ranger 4 probe, which crashed in 1962, and China's Chang'e 4 lander and Yutu 2 rover. Yutu-2 is still trundling along the lunar surface on its six wheels.

Yutu's latest results show that "soil" on the far side may be stickier than the near side, and there is a higher density of small craters.

The rocket stage could potentially cause damage to these historic spacecraft, if it lands on or near them. However, this is statistically unlikely. Current predictions have it landing in Hertzsprung crater, a long way from the Aitken basin where the Chinese spacecraft are operating.

Although there are no cameras to observe the crash, at some point NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter is likely to pass over and image the impact point.

We'll learn something about the geology of the location from the color differences and distribution of the ejected material. It's an opportunity to learn more about the moon's mysterious far side.

Changing attitudes to space junk

In the earlier Space Age, little thought was given to leaving what many call "trash" on the lunar surface.

The moon is sometimes considered a "dead" world because it has no life. The Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) Planetary Protection Policy does not require any special precautions for lunar activities.

But there is a growing awareness the moon has distinct environmental values of its own. The Declaration of the Rights of the Moon, created by a group of independent researchers, states the moon has "the right to exist, persist and continue its vital cycles unaltered, unharmed and unpolluted by human beings."

Canadian researchers Eytan Tepper and Christopher Whitehead have suggested the moon could be protected by giving it legal personhood, much like the Whanganui river in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The moon is struck by meteors all the time. In many ways, the Falcon 9 impact will be just another one. What makes it interesting is how it acts as a litmus test for changing public opinions about our responsibilities to the space environment.

So, a case of a billionaire littering the Moon... https://t.co/7ZqPhtgmL5January 26, 2022

The public is looking for accountability from space agencies and private corporations. As plans for lunar mining and habitation accelerate, hopefully it's a message that is ready to be heard.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook and Twitter. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Dr. Alice Gorman is an internationally recognized leader in the field of space archaeology. She is an Associate Professor in the College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences at Flinders University, where she teaches the Archaeology of Modern Society.

Her research focuses on the archaeology and heritage of space exploration, including space junk, planetary landing sites, off-earth mining, rocket launch pads and antennas.

She is a member of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, the Advisory Council of the Space Industry Association of Australia and the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

Her book "Dr. Space Junk vs the Universe: Archaeology and the Future" (2019) won the Mark and Evette Moran NIB People's Choice Award for Non-Fiction and the John Mulvaney Book Prize, awarded by the Australian Archaeological Association. It was also shortlisted for the Queensland Premier's Literary Awards, the NSW Premier's Literary Awards, and the Adelaide Festival Literary Awards.

Alice tweets as @drspacejunk and blogs at Space Age Archaeology.