Russian plans for space-based nuclear weapon to target satellites spark concern in US Congress

The capability is still in development and the launch of such a weapon does "not appear imminent."

Russia is reportedly developing a space-based nuclear weapon designed to disable or destroy satellites.

The United States Congress and America's European allies were informed of Russia's plans to develop the anti-satellite capability on Wednesday (Feb. 14). It's unclear what the exact nature of the planned weapon is — that is, whether it involves detonating a nuclear explosive in space or is another anti-satellite technology powered by a space-based nuclear reactor.

According to the intelligence presented to Congress, the U.S. military "does not have the ability to counter such a weapon and defend its satellites," according to a report in the New York Times. The report adds that U.S. government officials do not believe that such a weapon will be launched any time soon, but that there is "a limited window of time" to stop it from being launched and deployed.

Related: The Pentagon is worried about space weapons from Russia and China. Here's why.

Orbital nuclear weapons are currently banned due to the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, although there have been concerns of late that Russia might be backing out of the treaty in order to pursue further militarization of space.

Concerns over the development of such a weapon spread like wildfire on Wednesday (Feb. 14) after House Intelligence Committee chair Mike Turner (R-Ohio) issued a public statement asking President Biden to "declassify all information relating to this threat" so the U.S. government and its allies can "openly discuss the actions necessary to respond."

Other members of Congress have responded to Turner's request, downplaying the severity of the reported Russian pursuit of a nuclear space weapon. "The classified intelligence product that the House Intelligence Committee called to the attention of Members last night is a significant one, but it is not a cause for panic," said Rep. Jim Himes (D-CT), Ranking Member of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, in a statement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"As to whether more can be declassified about this issue, that is a worthwhile discussion but it is not a discussion to be had in public," Himes added.

House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.) issued a separate statement that downplays the threat posed by Turner's request. "I saw Chairman Turner's statement on the issue and I want to assure the American people there's no need for public alarm," Johnson said.

It's unclear why this particular intelligence was highlighted at this time, but there is some speculation that it could be related to Russia's Feb. 9 launch of a classified satellite known as Cosmos 2575.

\4 one more thing - I would not be surprised if this was linked to Cosmos 2575, which is a classified Russian satellite launched on Feb 9, which would be just enough time for the IC to do its thing... https://t.co/RQyRRhhZHJFebruary 14, 2024

On the same day Turner's comments went viral, the U.S. Space Force launched six satellites designed to detect and track missile launches.

A nuclear detonation in space could have both immediate and long-lasting effects in Earth's orbit. In the immediate aftermath, nuclear explosions could cause a multitude of damaging effects; pulses of high-energy radiation such as heat, x-rays and other radiation can "can damage nearby satellites and blind their sensors," according to a 2023 study by the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS).

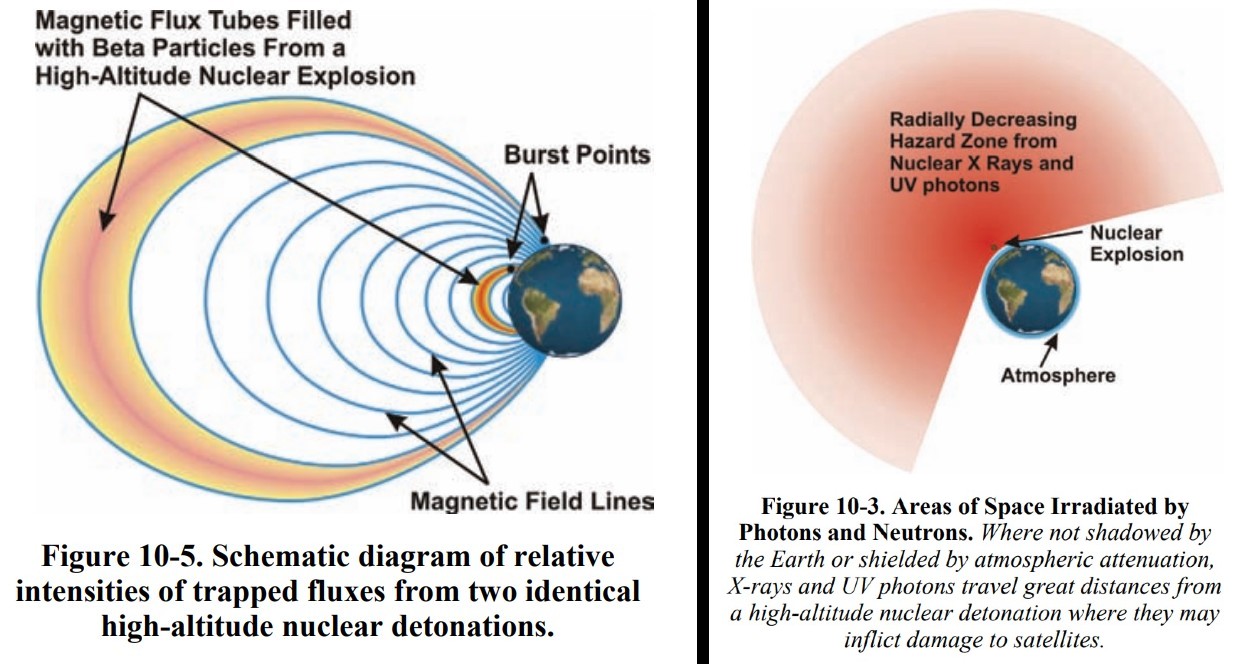

In terms of longer-lasting effects, the naturally occurring belts of radiation that surround our planet could trap radiation released by a nuclear explosion, producing "longer lasting radiation belts that caused deleterious effects to satellites then in orbit or launched soon thereafter," according to a report published in 2008 by the Commission to Assess the Threat to the United States from Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) Attack.

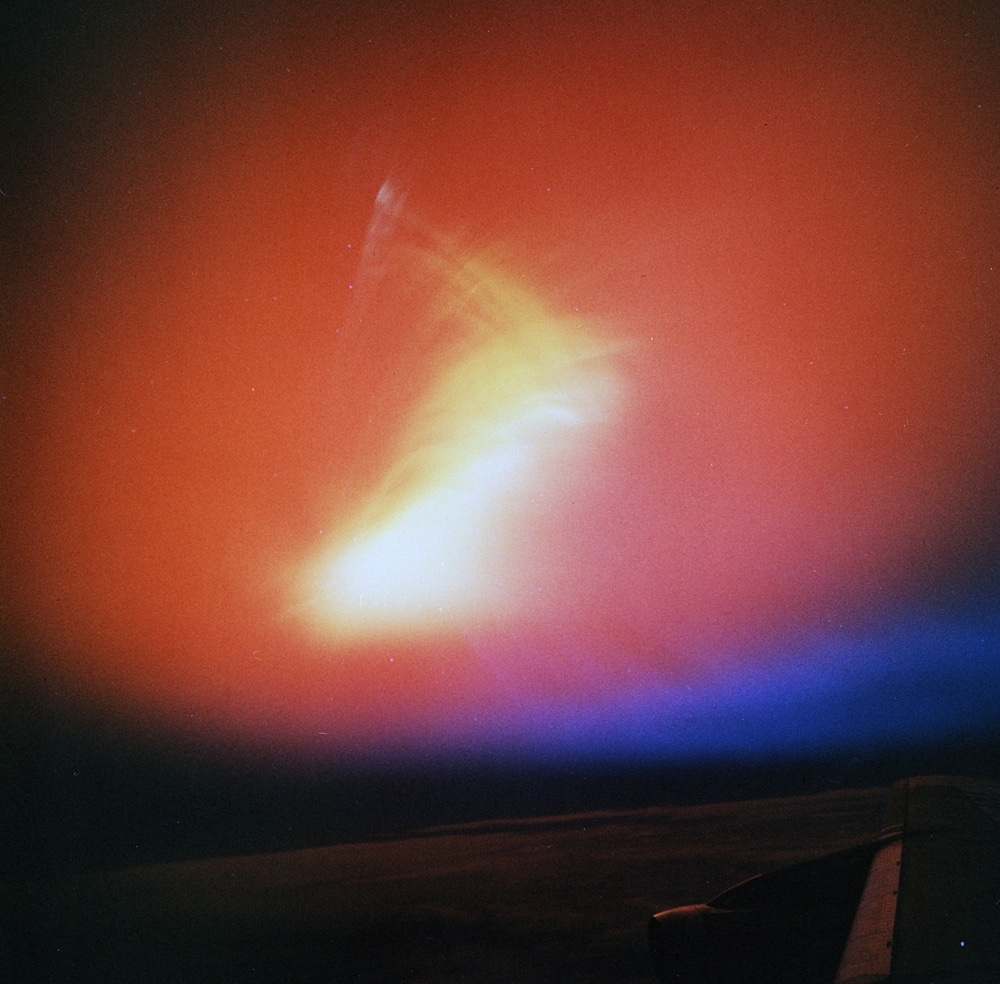

The same phenomenon was observed after the United States detonated a nuclear warhead at high altitude in 1962 during the "Starfish Prime" nuclear test conducted by the Atomic Energy Commission, a precursor to the Department of Energy.

The test saw a 1.4-Megaton device detonated 250 miles (400 km) above the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii. The Soviet Union also detonated three nuclear devices at high-altitude that same year.

Nuclear weapons aren't the only anti-satellite capabilities Russia — and other nations — are pursuing. Russia has been fielding ground-based lasers that can blind satellites, and has tested anti-satellite missiles widely condemned by the international community due to the amount of dangerous debris it produced in Earth'sorbit.

The U.S military has signaled in recent months that both Russia and the People's Republic of China (PRC) are seeking to turn space into a "warfighting domain" and are "deploying capabilities that can target GPS and other vital space-based systems," according to U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen Hicks.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Brett is curious about emerging aerospace technologies, alternative launch concepts, military space developments and uncrewed aircraft systems. Brett's work has appeared on Scientific American, The War Zone, Popular Science, the History Channel, Science Discovery and more. Brett has English degrees from Clemson University and the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. In his free time, Brett enjoys skywatching throughout the dark skies of the Appalachian mountains.