Russian and Soviet space stations throughout history

The Russian wing of the International Space Station is only growing. Despite a misfired thruster on its newly added laboratory module, Nauka, plans are still going ahead to launch another module, Prichal, in November 2021.

But today's Russian contribution to the ISS is only the newest phase of a space program that's been launching space stations since the 1970s. The winding history of Soviet and Russian space stations is filled with many successes — and many failures. And that half-century of space stations continues to influence Russia's stations today.

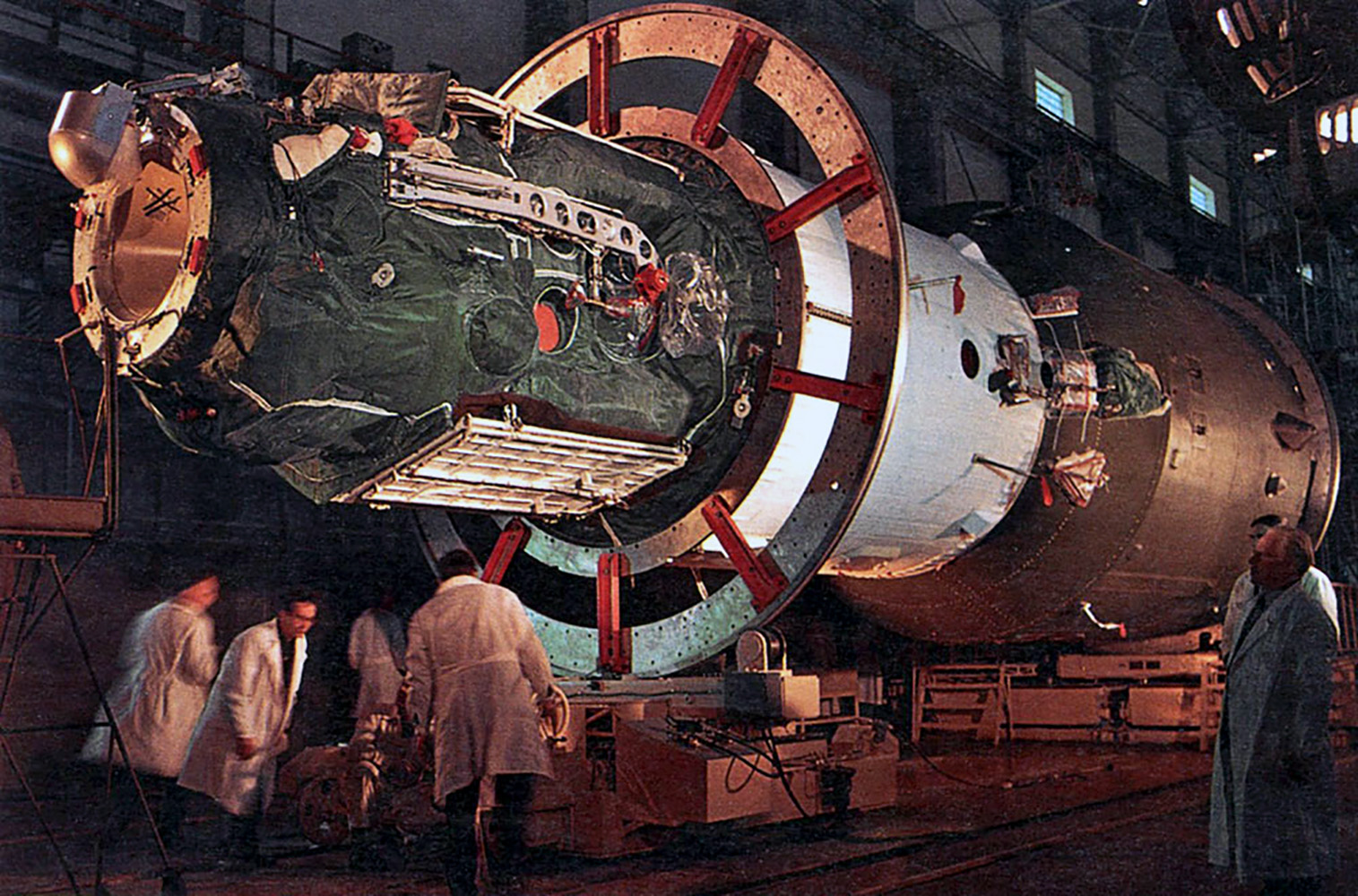

Here: Russia's Saylut 1, the world's first space station, is seen during preparations for its April 19, 1971 launch in this undated photo from the Russian space agency Roscosmos.

Salyut 1

The world's first space station, Salyut 1, lifted off in April 1971, just over 10 years after Yuri Gagarin became the first person to go to space. About the size of a small apartment, it was designed to house three cosmonauts at a time. It also held eight chairs and an ultraviolet telescope.

The Soviets' first attempt to send up a crew, the Soyuz 10 mission, was cut short when the Soyuz spacecraft carrying cosmonauts Vladimir Shatalov and Aleksei Yeliseyev failed to properly dock with Salyut 1. The second, Soyuz 11, was more successful. Its three cosmonauts (Georgy Dobrovolsky, Viktor Patsayev and Vladislav Volkov) stayed on board for a whole 23 days — in 1971, a world record.

But when Soyuz 11 tried to return to Earth, a pressure valve malfunctioned, causing its crew to asphyxiate. To this day, Soyuz 11's cosmonauts are the only space travelers to have ever passed away in space.

Salyut 2

In the 1970s, the Soviet Union actually had two space station programs. On top of the mainline Salyut launches, the Soviet military built their own space stations for a highly secretive program called Almaz. Soviet officials designed crewed military reconnaissance stations to observe the Earth from space, competing with what they saw as American attempts to do the same.

To veil those ulterior motives, Almaz launches were touted to the world as Salyut missions. In April 1973, the so-called Salyut 2 became the first Almaz station to go up. But it didn't last long: Merely days after it reached orbit, it was maimed by space debris from the rocket that launched it. By the end of May, the critically damaged station had crashed back into the atmosphere. No cosmonaut ever set foot inside.

Salyut 3

Another Almaz station, this one rather more successful, launched in June 1974. Information on this space station is still hard to come by, but it's rumored that the mission known as "Salyut 3" held Earth-facing cameras and some sort of onboard weapon.

Despite the station's militaristic purpose, cosmonauts visited it twice — though only one mission successfully docked with the station. Soyuz 14's crew, cosmonauts Pavel Popovich and Yuri Artyukhin, spent over two weeks on board in July 1974. More missions were planned, but the next of those, the Soyuz 15 mission carrying cosmonauts Gennady Sarafanov and Lev Dyomin, failed to dock. At this point, the Soviets decided to move on from Salyut 3 and upgrade their troublesome docking mechanisms.

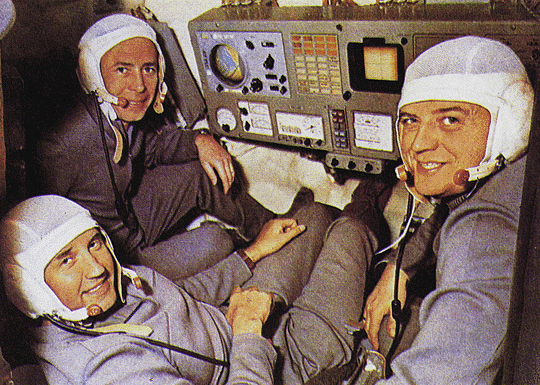

Here: The crew of the Soviet space mission Soyuz 14, Cmdr. Pavel Popovich (left) and engineer Yuri Artyukhin (right) are pictured before entering their Soyuz spacecraft prior to launch, on July 3, 1974.

Salyut 4

A successor to Salyut 1 had been in the works for some years. After two failed launches in 1972 and 1973, another station — Salyut 4 — finally reached orbit in December 1974.

Salyut 4 was little more than a slight upgrade to Salyut 1's design. It was fitted with a variety of telescopes: one pointed at the sun and two others watching the universe for X-rays. And it held a little garden for cosmonauts to grow peas and onions in space.

Two different crewed missions visited Salyut 4. Soyuz 17 docked in January 1975 with cosmonauts Aleksei Gubarev and Georgy Grechko, who stayed for about a month. Soyuz 18 arrived that May with Pyotr Klimuk and Vitaly Sevastyanov, staying for 63 days. By the end of its lifetime, the station was becoming uninhabitable: its life support was failing and its walls were coated with mold. Regardless, Salyut 4 stayed in orbit until 1977.

Salyut 5

The third and last of the Almaz launches, the station named Salyut 5 entered orbit in June 1976. Compared to Salyuts 2 and 3, it proved only somewhat longer-lasting.

The Soyuz 21 crew, cosmonauts Boris Volynov and Vitaly Zholobov, were Salyut 5's first visitors and had to leave early when a fuel leak contaminated the station's air during their July 1976 mission. Next came Soyuz 23, a mission carrying cosmonauts Vyacheslav Zudov and Valery Rozhdestvensky to Salyut 5 in October 1976, but that mission was cut short after failing to dock, and the crew went straight back to Earth. Finally, in February 1977, came the Soyuz 24 crew — cosmonauts Viktor Gorbatko and Yuri Glazkov — who managed to vent the station's air and freshen it up before entering and staying for a few weeks.

The station's plans called for a fourth mission, but by mid-1977, the station had already begun to run low on necessary fuel. It was deorbited that August.

Here: Soyuz 24 Cmdr. Viktor Gorbatko (left) and flight engineer Yuri Glazkov wave goodbye prior to their flight to the Salyut 5 space station, on Feb. 7, 1977.

Salyut 6

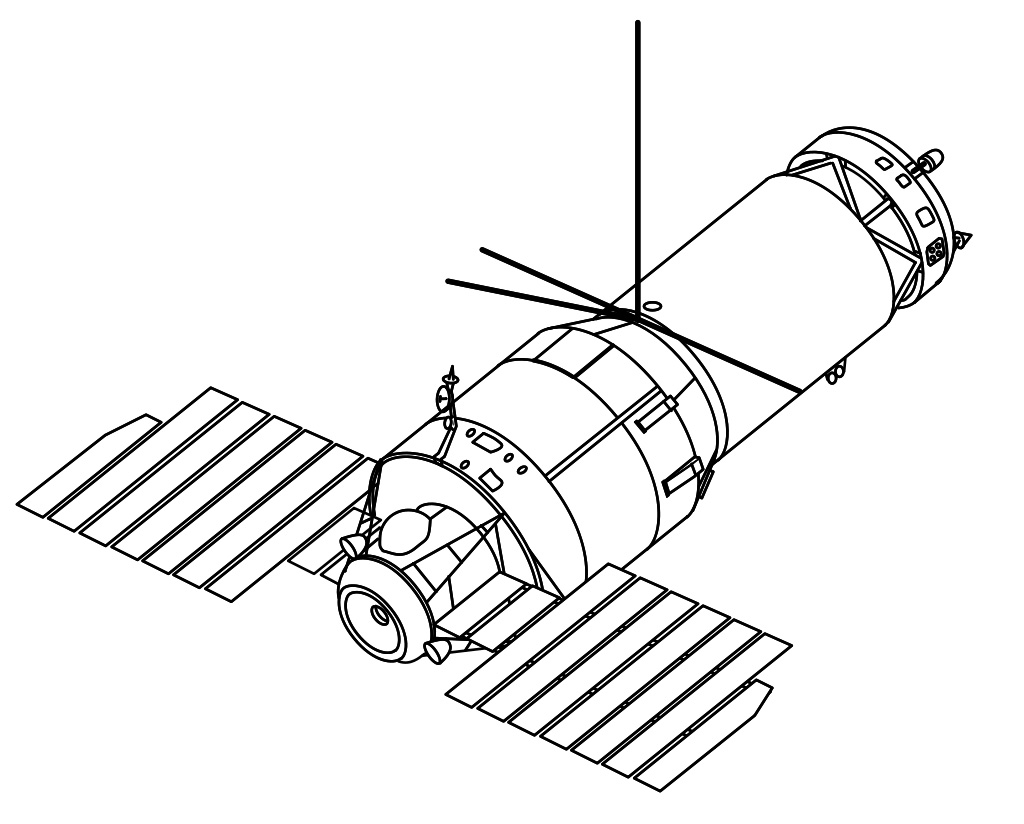

The Soviet space station program really began to hit its stride with Salyut 6. In many ways, Salyut 6 was the first truly long-lasting space station. Launched in September 1977, Salyut 6 welcomed dozens of cosmonauts during its five-year lifetime.

In a major improvement over its predecessors, Salyut 6 had two docking ports. That allowed some cosmonauts to reside on Salyut 6 long-term: as much as half a year, often sustained by uncrewed cargo resupply launches. Meanwhile, other crews could visit the station for shorter stays. Salyut 6 had an advanced telescope and an Earth-facing camera that cosmonauts used to help the Soviet Ministry of Agriculture examine crop sites.

Salyut 6's living standards were also a huge upgrade over its spartan predecessors. Now, Soviet space station-dwellers could avail themselves of sound-insulated walls, a gymnasium, a shower and cots for relatively comfortable sleep. And in 1980, Salyut 6's crew greeted the opening ceremony of that year's Summer Olympics in Moscow.

Salyut 7

Salyut 7 was quite similar to Salyut 6; in fact, it was originally Salyut 6's backup. It launched in April 1982, and like its predecessor, welcomed dozens of cosmonauts over the next several years, supported by uncrewed resupply missions.

Salyut 7's living conditions took yet another giant leap. Cosmonauts now had ergonomic seats, hot water, a refrigerator, and windows with shades. Portholes let in ultraviolet light to disinfect the interior. And Salyut 7's science experiments included the first plants to flower in space.

In 1985, when no cosmonauts were on board, Salyut 7’s electrical system shut down, and the station lost contact with the ground and began to spin uncontrollably. Impressively, the next crew — Soyuz T-13 — manually docked with the misbehaving station and, in sub-zero temperatures without life support, restored its power: an act which saved the station for another several years. Soviet planners wanted to retrieve Salyut 7 in the 1990s with a Buran space shuttle, but the Buran program was shuttered before that could happen. Ultimately, it re-entered the Earth's atmosphere in 1991.

Mir

The Salyut launches were all just a prelude to the Soviet Union's (and, later, Russia's) most ambitious space project yet. Much like today's International Space Station (ISS) or China's Tiangong space station, Mir was modular: it was assembled in space, one piece at a time, between 1986 and 1996. And at its heart was a retrofitted Salyut capsule.

That central module was home to Mir's crew. Around it were arrayed other modules. Kvant 1 was the astrophysics module, holding telescopes and X-ray detectors. Kvant 2 held cargo, scientific equipment, and an incubator for quail eggs, which successfully hatched in space for the first time in 1990. Kristall held a few miniature furnaces and a docking port for the Buran space shuttles that never launched.

No fewer than 28 missions visited Mir during its 15-year-long lifespan. Mir hosted spacefarers from over a dozen countries, including some of the former Soviet Union's old rivals in Western Europe and America; in fact, Mir's last expansion, in 1995 and 1996, brought three more modules where NASA's space shuttle could dock.

International Space Station (Russian Segment)

The Salyut program didn't end with Mir. Another Salyut capsule was initially planned for a Mir 2, but amidst the economic crises of 1990s Russia, that never materialized. Instead, that Salyut capsule was retrofitted into something else: Zvezda, the heart of the Russian wing of the International Space Station.

Zvezda contains the living quarters of the Russian wing. But it wasn't the first Russian part of the ISS; that was Zarya, which in 1998 was the first module of the ISS to launch. It's now mainly used for cargo and storage. Other modules in the Russian section include Poisk, an airlock which joined the ISS in 2009, and Rassvet, a docking module which joined in 2010.

There was once another module, a second airlock called Pirs. But in July 2021, it was detached to make way for another module: Nauka, a laboratory module. And in 2022, joining Nauka will be a new dock, Prichal.

Rahul Rao is a graduate of New York University's SHERP and a freelance science writer, regularly covering physics, space, and infrastructure. His work has appeared in Gizmodo, Popular Science, Inverse, IEEE Spectrum, and Continuum. He enjoys riding trains for fun, and he has seen every surviving episode of Doctor Who. He holds a masters degree in science writing from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program (SHERP) and earned a bachelors degree from Vanderbilt University, where he studied English and physics.