Japan's priceless asteroid Ryugu sample got 'rapidly colonized' by Earth bacteria

"The fact that terrestrial microbes are the Earth's best colonizers means we can never completely discount terrestrial contamination."

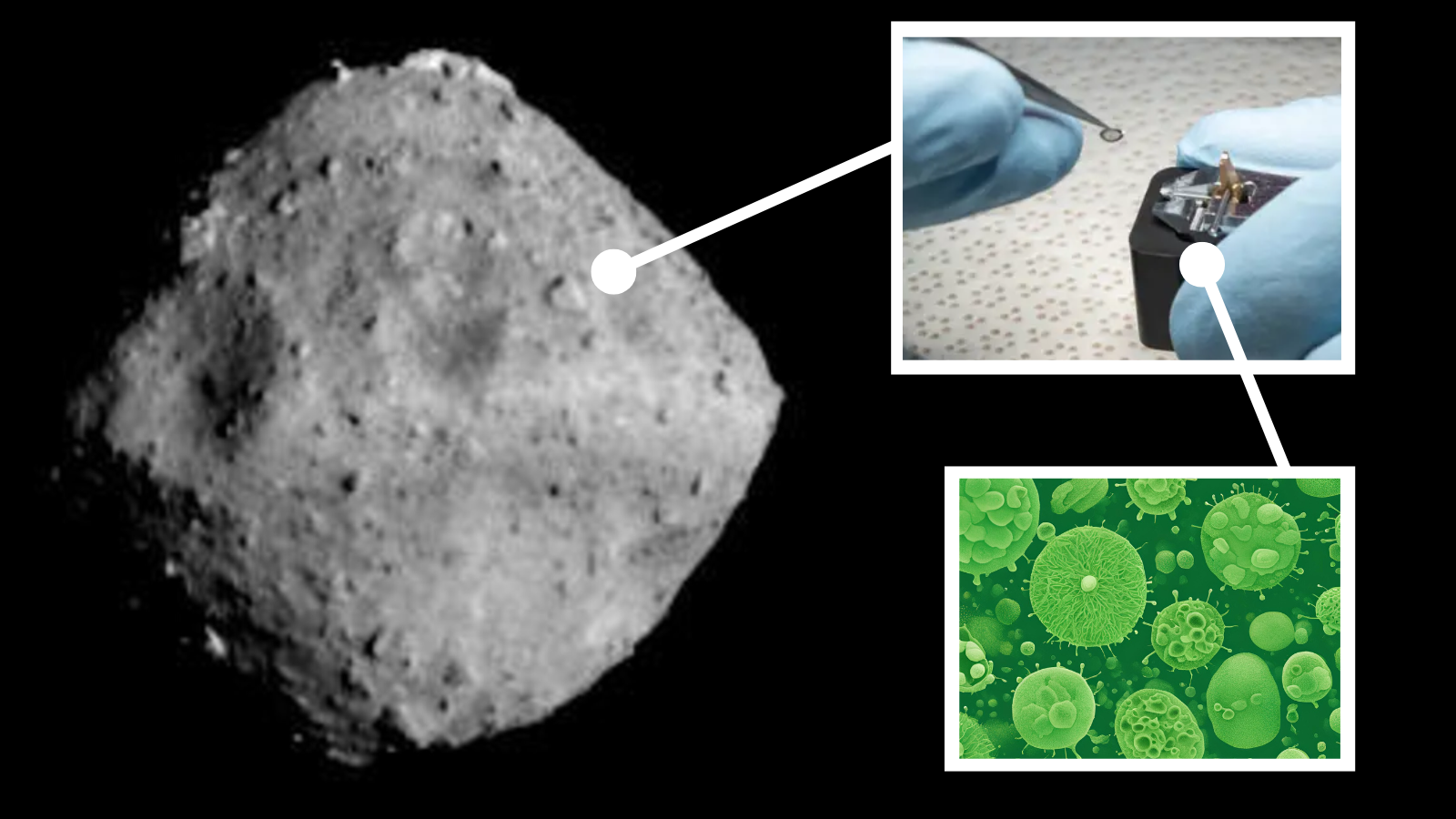

Scientists have discovered that a sample of the asteroid Ryugu was overrun with Earth-based life forms after being delivered to our planet. The research shows how successful terrestrial micro-organisms are at colonization, even on extraterrestrial materials.

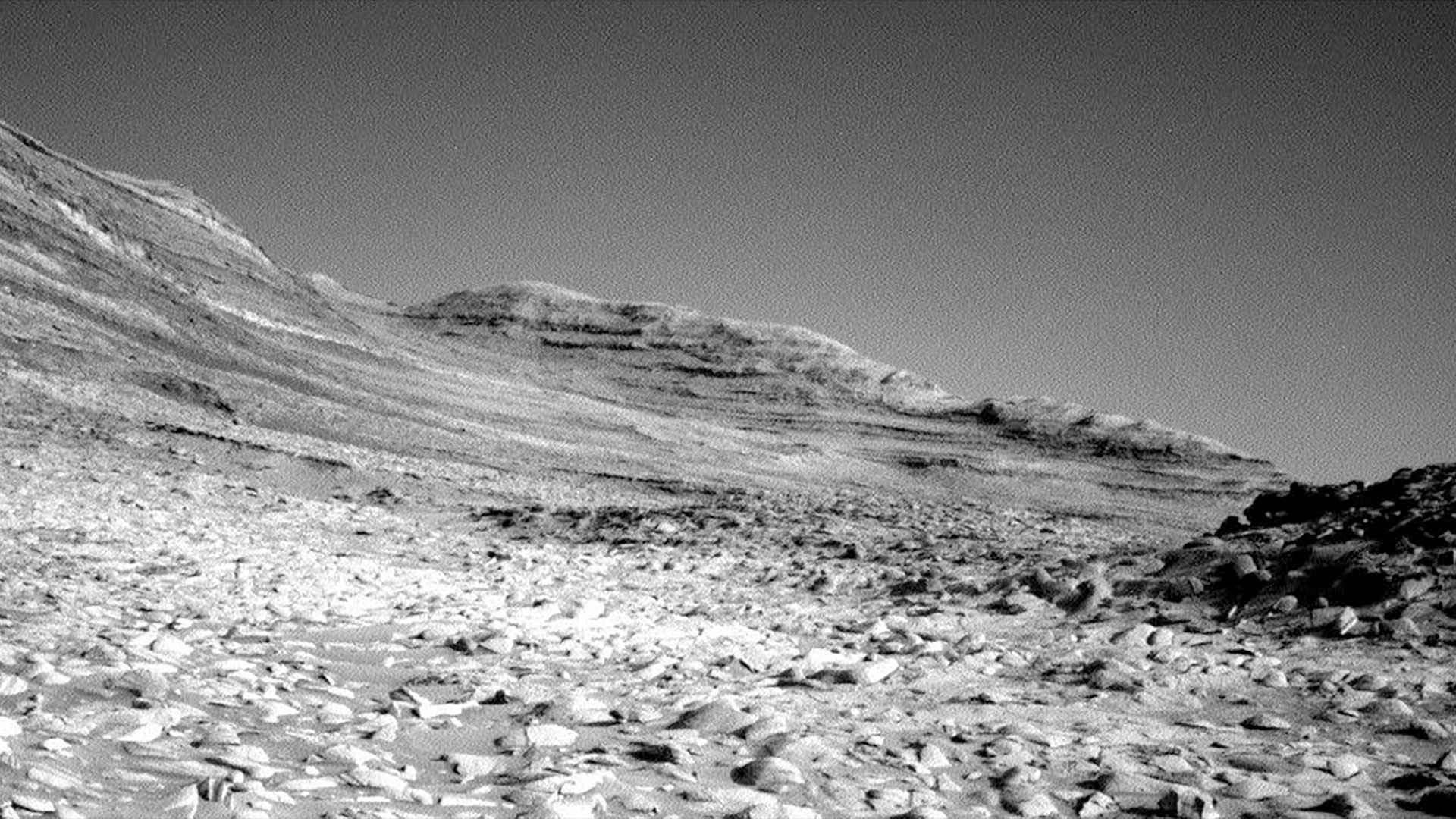

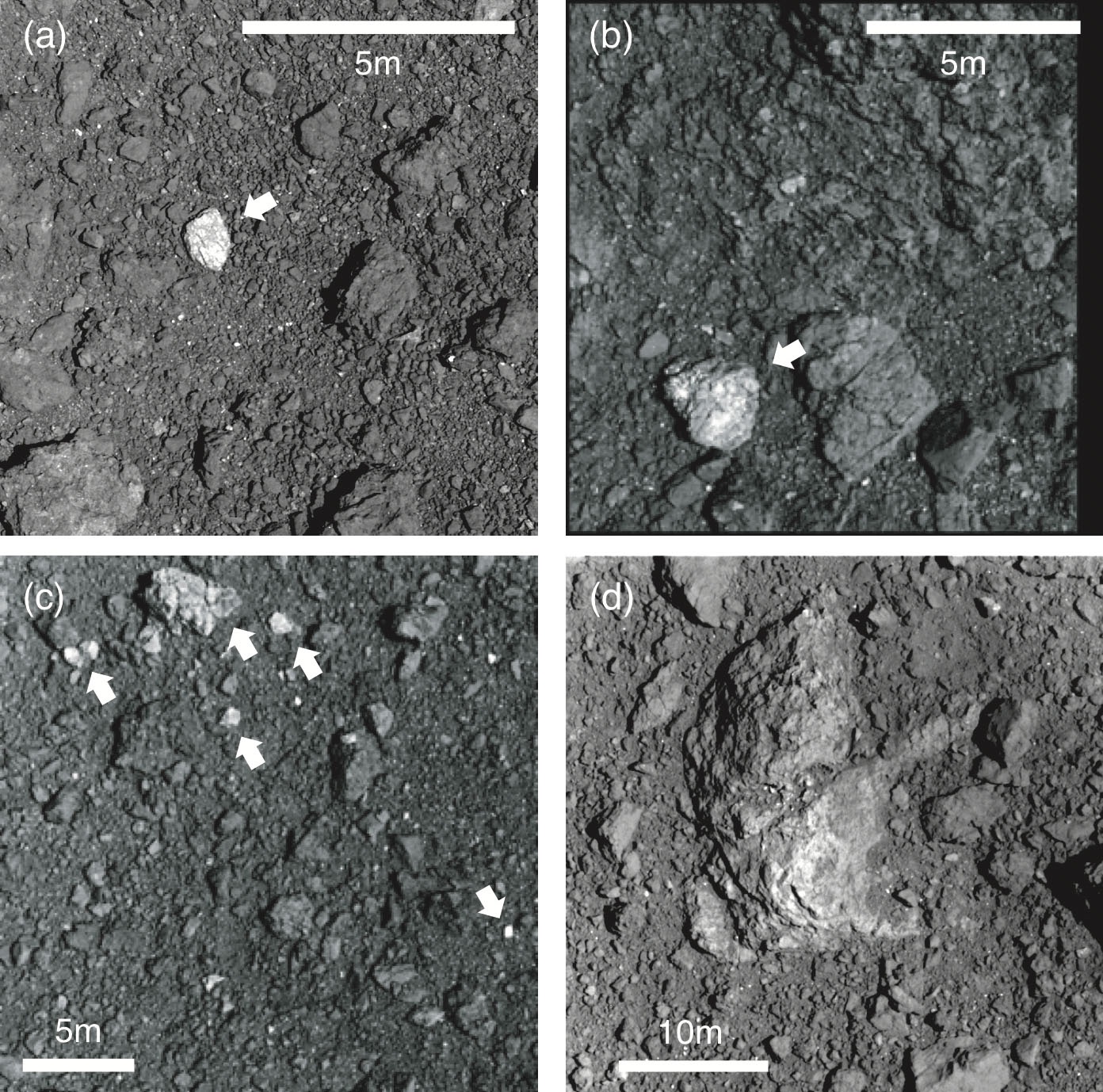

The samples were collected by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA)'s spacecraft Hayabusa2, which launched in December 2014 and rendezvoused with Ryugu in June 2018. Haybusa2 then spent a year studying the asteroid, which has a diameter of around 3,000 feet (900 meters), before diving to its surface and scooping out a sample.

This Ryugu sample was returned to Earth on Dec. 6, 2020, but Haybusa2 continued on to study more asteroids. The sample was split and sent to various teams of scientists, including the team that made this new discovery.

"We found micro-organisms in a sample returned from an asteroid. They

appeared on the rock and spread with time before finally dying off," team leader Matthew Genge of Imperial College London told Space.com. "The change in the number of micro-organisms confirmed these were living microbes. However, it also suggested they only recently colonized the specimen just before our analyses and were terrestrial in origin."

The discovery took the form of rods and filaments of organic matter, which the team interpreted as filamentous microorganisms. Exactly what type of microorganisms these were isn't known by the team, but Genge has a good idea of what they may be.

"Without studying their DNA, it is impossible to identify their exact type," the researcher said. "However, they were most likely bacteria such as Bacillus since these are very common filamentous micro-organisms, particularly in soil and

rocks."

Of course, with humanity currently engaged in the search for microbial life beyond the limits of our planet, particularly on Mars, the question is, could these micro-organisms have been present on Ryugu when the sample was gathered and thus could they represent alien life?

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Disappointingly, the team has successfully and conclusively ruled this out.

"Before we prepared the sample, we performed nano-X-ray computed tomography, and no microbes were seen," Genge said. "In any case, the change in population suggests they only appeared after the rock was exposed to the atmosphere, more than a year after it was returned to Earth."

The researchers found that within a week of exposing the specimen to the Earth's atmosphere, 11 microbes were present on its surface. Just a week later, the population of terrestrial colonizers had grown to 147.

"It was very surprising to find terrestrial microbes within the rock," Genge said. "We usually polish meteorite specimens, and microbes rarely appear on them. However, it only needs one microbial spore to cause colonization."

While these results don't really tell us anything about extraterrestrial life, they do speak to the hardiness of life forms here on Earth, particularly micro-organisms. The findings also have implications for the effects that spacecraft and rovers could have on the planets they visit.

"It shows that microorganisms can readily metabolize and survive upon

extraterrestrial materials. On Earth, there is abundant home-grown

organic material available, but on planets such as Mars, extra-martian

organic materials may support an ecosystem," Genge said. "Our findings suggest that space missions could be contaminating space environments. It also shows that terrestrial microorganisms are adept at rapid colonization."

Fortunately, as Genge pointed out, space agencies employ planetary protection efforts designed to minimize the likelihood of contamination.

Genge also warns that scientists should be cautious of contamination when future samples are returned to Earth before assuming the detection of extraterrestrial life.

"The fact that terrestrial microbes are the Earth's best colonizers means we can never completely discount terrestrial contamination," the researcher continued. "Most of the time, contamination is not a problem as long as you know its source. The problem comes when scientists attempt to claim that the 'pristine' nature of a specimen is evidence that features are extraterrestrial."

As for the Imperial College of London researcher and his team, they are looking forward to examining more asteroid samples, hopefully free from visitors from Earth!

"The team is continuing to study samples from Ryugu and Bennu. Hopefully, next time without terrestrial bacteria colonizing these materials!" Genge concluded.

The team's research was published in the journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

-

Unclear Engineer It seems like the researchers should have analyzed the DNA of those microbes. It would have provided more conclusive evidence of terrestrial origin..Reply

With recent evidence that microbes can colonize and survive in rock deep within Earth, we should not be assuming that they cannot also do that in other rocky materials off-Earth. And it should not be surprising if extraterrestrial microbes revive and begin to colonize on Earth, only to soon die from competition with terrestrial competitors or some sort of poisoning from an environmental factor unfamiliar to them.

That was basically the original premise for "War of the Worlds", where the invaders were able to easily defeat human military defenses but soon succumbed to terrestrial microscopic infections. So, it is not a novel concept. -

Ken Fabian @Unclear EngineerReply

Not DNA analysis but thorough examination earlier showed no presence of microbes. I don't think their contamination-not-ryugu-origin conclusion lacks a sound basis -

Disappointingly, the team has successfully and conclusively ruled this out.

"Before we prepared the sample, we performed nano-X-ray computed tomography, and no microbes were seen," Genge said. "In any case, the change in population suggests they only appeared after the rock was exposed to the atmosphere, more than a year after it was returned to Earth." -

Unclear Engineer I think it is probably terrestrial contamination.Reply

But, I think the evidence stops short of "conclusiveness", given that we don't actually have any idea how extra-terrestrial life would work.

Just looking at the outside surface with an electron microscope does not rule out something on the inside that propagates to the outside, but then dies.

Considering that we are frequently being surprised by what microscopic terrestrial life forms can do, it is hard to develop conclusive logic about what extraterrestrial life forms might be able to do, especially when exposed to a new (to them) environment (ours).