How satellite data has proven climate change is a climate crisis

"The 30-year-long curves of sea level rise are unquestionable evidence that our climate is changing."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

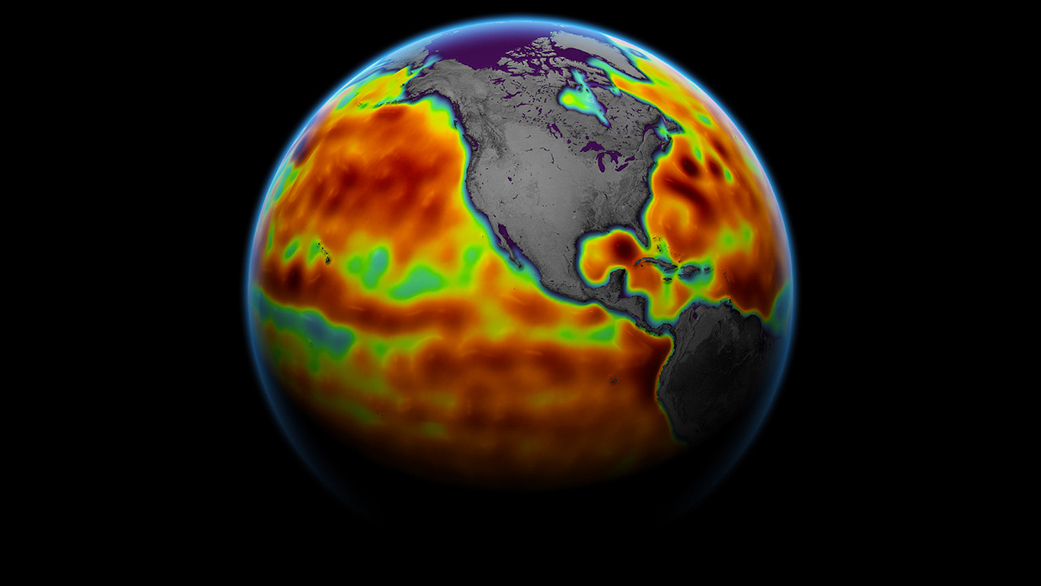

The year 2024 was a record-breaking one, and not in a good way. In July, Earth's average temperature was the highest it has been in at least 175 years, with July 22 specifically being the hottest day on record. This past summer was the hottest summer since about the year 1880, this year's hurricane season started with Beryl — the earliest Category 4 hurricane on record — and a report published in June confirmed that human-driven global warming is at an all-time high.

But it isn't just the headline-making record-breakers that scientists are worried about. As of this year, glaciers are melting at unprecedented rates due to all this human-induced heat, sea levels are irreversibly rising as a result of those glaciers melting, coastal communities are being ravaged by storms exacerbated through such sea level rise combined with high temperatures, and animals are getting evicted from their homes because Earth is changing too much, too quickly. Just last month, we saw Hurricane Helene destroy towns and claim lives — and its strength has indeed been connected to climate change.

It's certainly heavy to see the facts laid out like this, especially considering how much those paragraphs leave unsaid. This feeling, however, brings to the forefront something very important: it is, on a baseline level, valuable that this information exists at all. Perhaps the biggest limiting step in the fight against climate change is turning facts into actionable tasks and, in turn, convincing policymakers to start making major changes in the way our world is run. The climate crisis is a deceptively political problem, meaning the future of Earth hinges on data — and, depending on how you see it, that data hinges on an unlikely source: space exploration.

"The only way we can draw connections between the various phenomena that drive the complex functioning of our planet, tease out the natural and the human-driven, is to connect the dots among them," Cedric David, a scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California, told Space.com.

"For this, we need an ongoing fleet of space sentinels up high in space," he said. "The same way we do annual checkups at the family doctor, we need to diagnose the health of our own planet."

Related: World Space Week 2024: How space technology arms scientists fighting climate change

What exactly do climate satellites do?

The word "satellite" is thrown around a lot these days, but in basic terms, it just refers to any object sent to live in our planet's orbit to perform a designated task. We have communications satellites to make our cellphones work, navigation satellites to make Google Maps give us correct driving directions and experimental satellites for the purpose of pure science, like this one that's presently testing solar sail technology.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Amid the satellite party, we also have climate satellites.

"NASA and other international space agencies inspire the world with our exploration of planets in our solar system and beyond," David said. "But a significant impact that space research has had has also been a much better understanding of our own planet."

For example, there are satellites with spectrometers that can reveal the concentration of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere, which is important because experts have revealed that atmospheric carbon dioxide levels are increasing primarily due to the burning of fossil fuels like coal and oil. More carbon dioxide in the atmosphere means a "supercharged" greenhouse gas effect, as the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) puts it — and a supercharged greenhouse gas effect means a global temperature rise. To be clear, there is such a thing as "natural" climate change. But, right now, nature isn't the primary driver of global warming. Human activities are, as research has shown time and again.

Furthermore, there are many satellites, like NASA's Landsat spacecraft, that can procure images of how forests are decreasing in size as industries chop them down to make room for commercial ventures. Imagery can also help track things like changing animal habitats, forced wildlife migration and diminishing food supply for certain species. There are also spacecraft with lasers that can help measure the rate at which ice caps are melting. Still others have synthetic aperture radars that show how our planet responds to earthquakes, which could increase in frequency as the Earth warms.

"Having worked at NASA for 10 years, I've seen a good number of remote observations that have really given me pause to reflect," David said. "The most incredible, to me, is gravimetry."

Satellite gravimetry helps scientists measure Earth's gravitational influence — and most importantly, subtle changes in our planet's gravitational field. As gravitational force is directly correlated with objects of mass, this means the technique can precisely measure when ice mass is lost, how oceans are rising and even fluctuations in groundwater supply. "Satellites can see what we cannot with our own eyes: changes in deep underground water storage that would require us to dig deep in the ground to witness firsthand," David said.

"That's just mind-blowing."

Earth's future is our future

The list goes on — and that's a good thing. Having so much data allows scientists to do their due diligence, compiling extensive amounts of evidence for people in power to peruse before making climate-impacting decisions. During huge climate meetings— the COP conferences are probably the most well-known — that evidence can be presented to officials as part of a case for change. Without information, communication isn't easy.

But oftentimes, satellite data is practical in the short term as well.

Hurricane watchers, for instance, help meteorologists predict where storms are going to fall — a crucial task, as these storms are bound to grow in intensity as well as frequency as the climate warms — and methane emission trackers can identify where exactly greenhouse-gas hotspots are located.

David also points out that, in a 2018 report, the U.S. National Academies recommended NASA build a series of spacecraft that will together form the Earth System Observatory, or ESO. This observatory, he explains, would have the duty of sensing the movements of our planet's atmosphere, the generation of rain, the ups and downs of continents and the continued movements of mass around the world.

However, there's still a lot more that can be done.

"One grand challenge yet remains: the accurate measure of our snowpacks from space. Snow is notoriously difficult to quantify; we can see the area it covers, but it's still difficult to sense how deep it is and how dense it is," he said. "Given that many regions — including California, where I live — for which snowmelt is a primary source of freshwater, advancing our understanding of snow in areas that are difficult to access is imperative."

David believes all of this information is "absolutely essential." But I asked him to pick the one most useful kind of satellite data to have while forming possible solutions to climate change; he picked radar altimetry.

"We've had a series of radar altimetry satellites circling around our Earth in constant operation since 1992 that have allowed us to see the undeniable: oceans are in constant rise," he said. "The 30-year-long curves of sea level rise are unquestionable evidence that our climate is changing."

In other words, we have a continuous stream of data telling us the same thing again, and again, and again: Earth's climate is changing, and it's because of the humans that populate it. It is this kind of data that should be dictating our response.

"As we continue to explore our universe and inspire people, we are constantly reminded that, so far, the only place where we have found life is right here on Earth," David said. "We can keep looking for a Plan B, but so far, there is only Plan A: our own planet."

This article is part of a special series by Space.com in honor of World Space Week 2024, which ran from Oct. 4 to Oct. 10 and explored how space technology can help fill the toolboxes of climate scientists.

Monisha Ravisetti is Space.com's Astronomy Editor. She covers black holes, star explosions, gravitational waves, exoplanet discoveries and other enigmas hidden across the fabric of space and time. Previously, she was a science writer at CNET, and before that, reported for The Academic Times. Prior to becoming a writer, she was an immunology researcher at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. She graduated from New York University in 2018 with a B.A. in philosophy, physics and chemistry. She spends too much time playing online chess. Her favorite planet is Earth.