Astronomers plan to take their defense of darkness to another level.

The dark skies that optical astronomers rely on, and many of the rest of us appreciate, are under threat from satellite megaconstellations like SpaceX's burgeoning Starlink broadband network, researchers have stressed.

Many in the astronomy community have therefore been spurred to action — studying the problem in detail, for example, alerting the public about the seriousness of the issue, and advising satellite operators on how to make their spacecraft dimmer and less obtrusive. But some scientists are now taking another step, one that they hope will have even more significant and lasting effects.

Related: The most historic satellites ever launched

That big step began this week with an online workshop called "Dark and Quiet Skies for Science and Society," which was organized jointly by the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) and the International Astronomical Union. The workshop's slate on Thursday (Oct. 8) was devoted to the coming megaconstellations, discussing the impact they may have on astronomy and ways to mitigate the effects.

The Thursday discussions will lead to a report that will be submitted to the United Nations' Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, said workshop attendee Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer and satellite tracker based at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

"The long-term hope is that we can persuade the UN to issue guidelines about protecting the night sky that will reflect a reasonable compromise between the satellite operators and the needs of astronomers," McDowell told Space.com. Those guidelines will then be picked up by national governments as licensing regulations, if all goes according to plan, he added.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Related: SpaceX's Starlink satellite megaconstellation launches in photos

Such guidelines might encourage operators to design their spacecraft to be as dim as possible and to keep them at altitudes lower than 360 miles (600 kilometers), McDowell said. (In higher orbits, satellites catch the sun for longer stretches and are therefore visible through more of the night. It also takes longer for dead satellites in higher orbits to fall back to Earth.)

This approach is a new one for the astronomy community, which has not gotten involved much in space-governance issues, he added. Neophytes though they are in this area, McDowell and his colleagues don't have unrealistic expectations about the pace of progress.

"It's the very beginning of a long struggle," McDowell said. "And so in the meantime, we may have a few years, I think, where we'll really see significant impacts on ground-based astronomy."

Those impacts are expected to come primarily from three big commercial constellations, all of which are designed to beam internet service from low-Earth orbit (LEO): SpaceX's Starlink, OneWeb's network and Project Kuiper, which will be run by Amazon. SpaceX and Amazon plan to keep their craft near or below the 360-mile line, but OneWeb's constellation will fly much higher, about 750 miles (1,200 km) up.

Amazon has said that Project Kuiper will consist of about 3,200 spacecraft. SpaceX has permission from the U.S. Federal Communications Commission to loft 12,000 Starlink satellites and has proposed a "Generation 2" system that would be 30,000 strong. OneWeb's architecture, meanwhile, envisions nearly 48,000 spacecraft eventually.

For perspective: Humanity has launched fewer than 10,000 objects to the final frontier since the dawn of the space age in 1957, according to UNOOSA.

Starlink: SpaceX's satellite internet project

It's unclear how many of these internet satellites will actually reach space. SpaceX has already launched nearly 800 Starlinks and plans to continue lofting 60-satellite batches relatively frequently for the foreseeable future. Amazon hasn't launched any Kuiper craft yet, however. OneWeb has orbited 74, but the company recently went through bankruptcy and was bought by a group co-led by the United Kingdom national government.

So there's a range of possible outcomes, most of which will worry astronomers. For example, McDowell characterized the impact of 10,000 LEO internet satellites on astronomical observations as "severe" and that of 100,000 spacecraft, a tally that could result if all the companies hit their most ambitious targets, as "catastrophic."

The impacts won't be spread evenly across astronomical campaigns, either. For example, projects that need to observe close to the horizon around twilight, such as hunts for near-Earth asteroids, will be hit particularly hard, McDowell said.

Astronomers have had productive conversations with SpaceX, which has worked to reduce the brightness of its 570-lb. (260 kilograms) Starlink craft. (The first few Starlink batches were surprisingly bright, which galvanized researchers' concern.) For instance, the company has added "visors" to Starlink spacecraft to keep sunlight off their most reflective surfaces and is orienting the satellites to dim them from a ground observer's perspective.

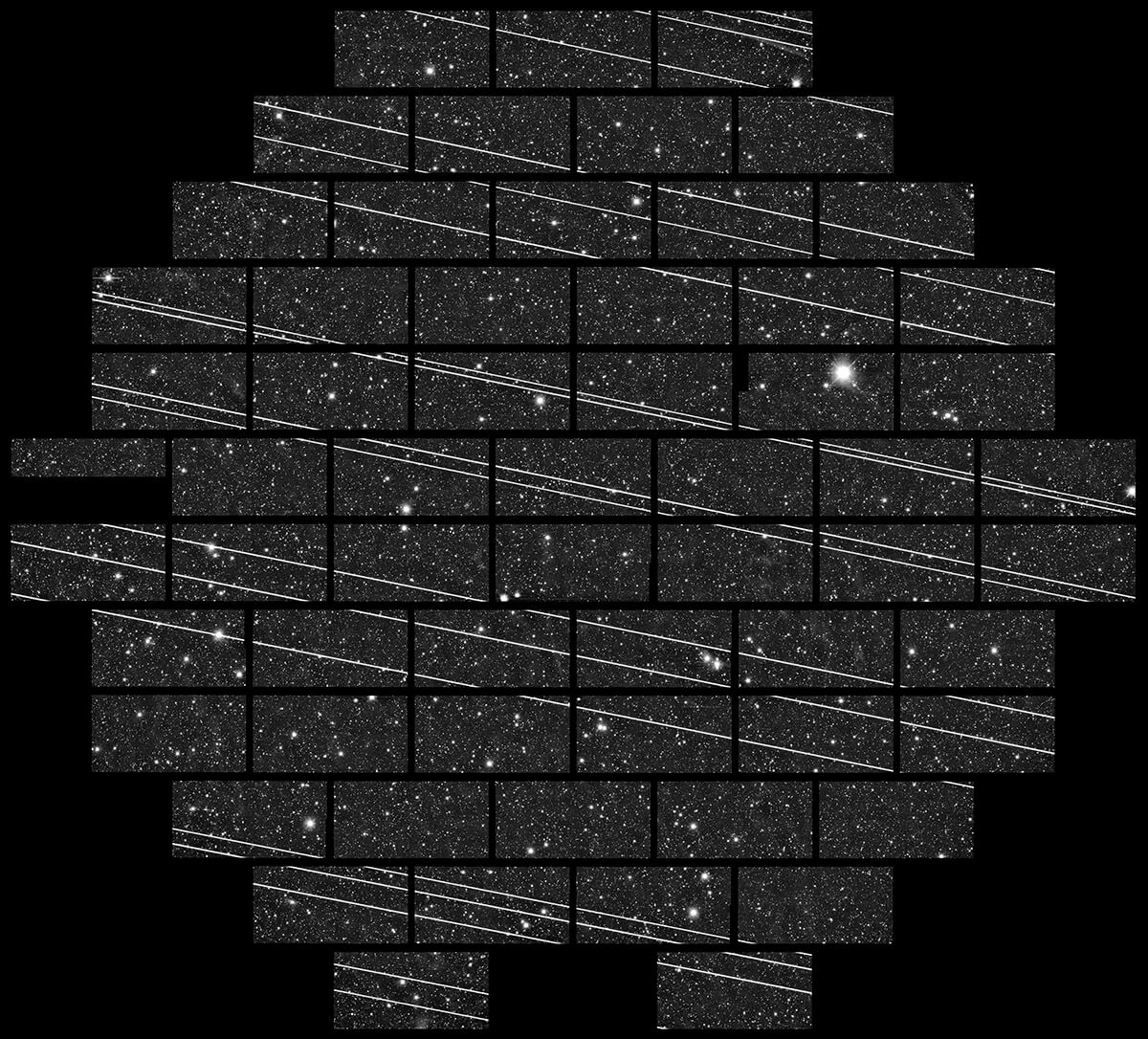

McDowell said that he appreciates such efforts, which will likely ensure that Starlink satellites are too faint to see with the naked eye for the most part. (They'll still show up as bright streaks when they wander into a sensitive telescope's field of view, however.)

But the issue is larger than SpaceX, Amazon, OneWeb or any other company, he stressed. And that's why he and his colleagues are moving in this new direction.

"The right solution is to engage the UN and have some best practices agreed," McDowell said.

UN guidelines could also help mitigate another potential impact of the coming megaconstellations — an increasingly cluttered orbital environment. And they could come in especially handy when big satellite networks go international, which is bound to happen at some point. Indeed, McDowell said he had recently seen the first detailed proposal for a Chinese megaconstellation.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.