Look up! Saturn shines bright, shows off rings as it reaches opposition.

This year Saturn's northern hemisphere will be tilted in our direction at a slant that allows for a nice look at Saturn's rings.

Gear up for Saturn's annual show in the night sky!

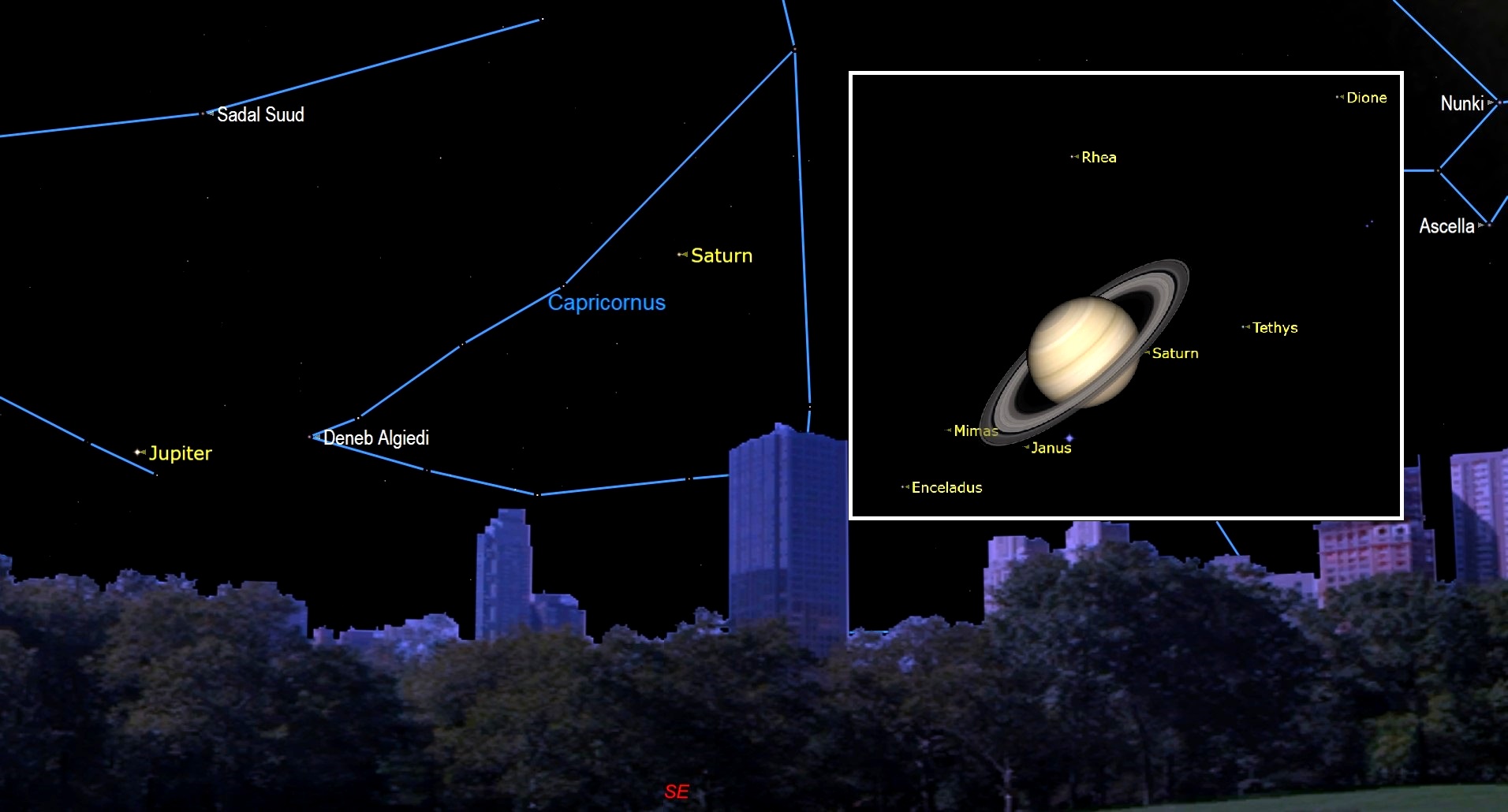

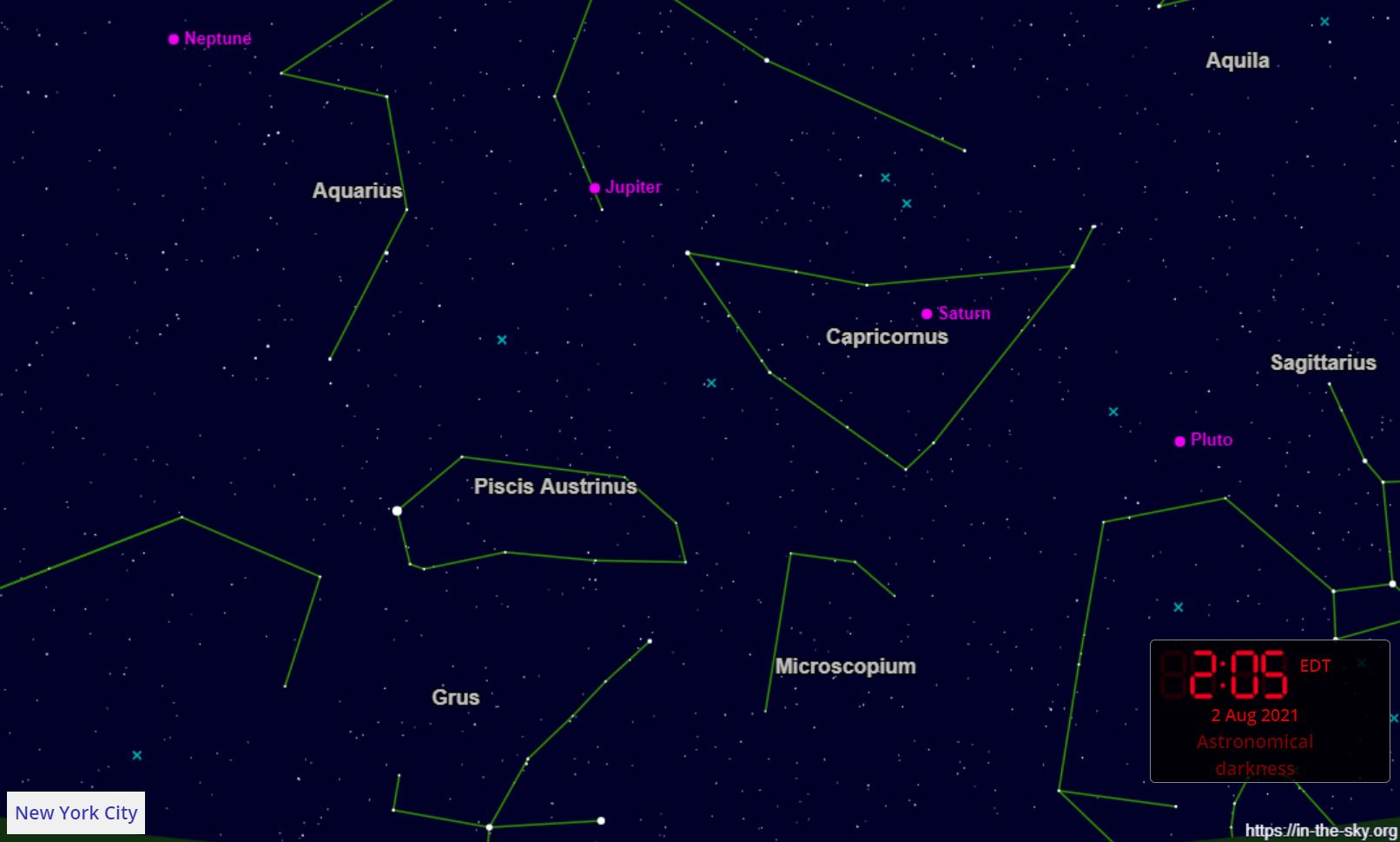

Starting Monday (Aug. 2), you can find Saturn shining in the sky as part of a celestial phenomenon called opposition. Earth and the ringed planet will be on the same side of the sun and connected with our star by an invisible line, allowing skygazers on Earth to see a fully illuminated Saturn. Saturn reaches this brightest point at about 2 a.m. EDT (0600 GMT) on Monday, according to the website EarthSky.org. It will be highest in the sky around midnight local time and located in the constellation Capricornus.

Skywatchers will be able to spot several gems, the most obvious being Saturn's rings. This year, Saturn's northern hemisphere will be tilted in our direction at a slant that allows for a nice look at Saturn's rings inclined at an angle of 18 degrees with respect to Earth, according to the website In-The-sky.org. The angle should also allow sunlight to reflect off the icy rings to illuminate them from our perspective.

Related: The brightest planets in August's night sky: How to see them (and when)

Read more: Saturn's summer season ends as Hubble telescope watches (photos)

Viewers may also get to see Titan, Saturn's largest moon. "Through a small telescope, Titan is actually pretty easy," astronomer Phil Plait told NPR. "If you take a look, you might see a little star right next to Saturn. That might very well be Titan — you can go online and find planetarium software" to confirm it, he said.

Carlos Blanco, a particle physicist at Princeton University and an avid skywatcher, told Space.com that he recommends viewing Saturn with a telescope that offers a narrow field of view and high magnification.

"In the sky, planets are unique in that they are relatively bright but almost point-like, as opposed to the moon or the Andromeda galaxy, which extend several degrees in the sky," he said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"So to get a good look at them, you want to have a scope such that the image you see in the viewfinder is roughly as big as the planet. In other words, the circle that the viewer makes in the sky should be very tight around that point of light," he said. "Roughly speaking, the higher the magnification power of the telescope, the smaller the field of view, and vice versa."

Blanco recommends an 8-inch Dobsonian telescope; check out Space.com's list of this year's best telescopes for recommendations.

Don't worry if you can't locate a telescope in time, because Saturn is one of the most distant objects that people can view in the sky with the naked eye. As a general rule of thumb, Plait recommends finding the brightest point in the night sky (after Venus has set, that is — that planet is easy to recognize because it shines low in the sky after sunset or before sunrise). That bright point is Jupiter, he told NPR, and Saturn will be the next-brightest point in the sky, west of Jupiter.

Understanding how opposition works will help, too. Opposition occurs when a planet appears opposite the sun in Earth's sky. In this case, Saturn will climb high in the Northern Hemisphere's sky at night because it is opposite the sun, which is high in the sky on the daytime side.

Follow Doris Elin Urrutia on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.