Solar eclipses seen by long-dead Cassini spacecraft shed new light on Saturn's rings

Clues about the transparency of Saturn's rings were in Cassini's data all along.

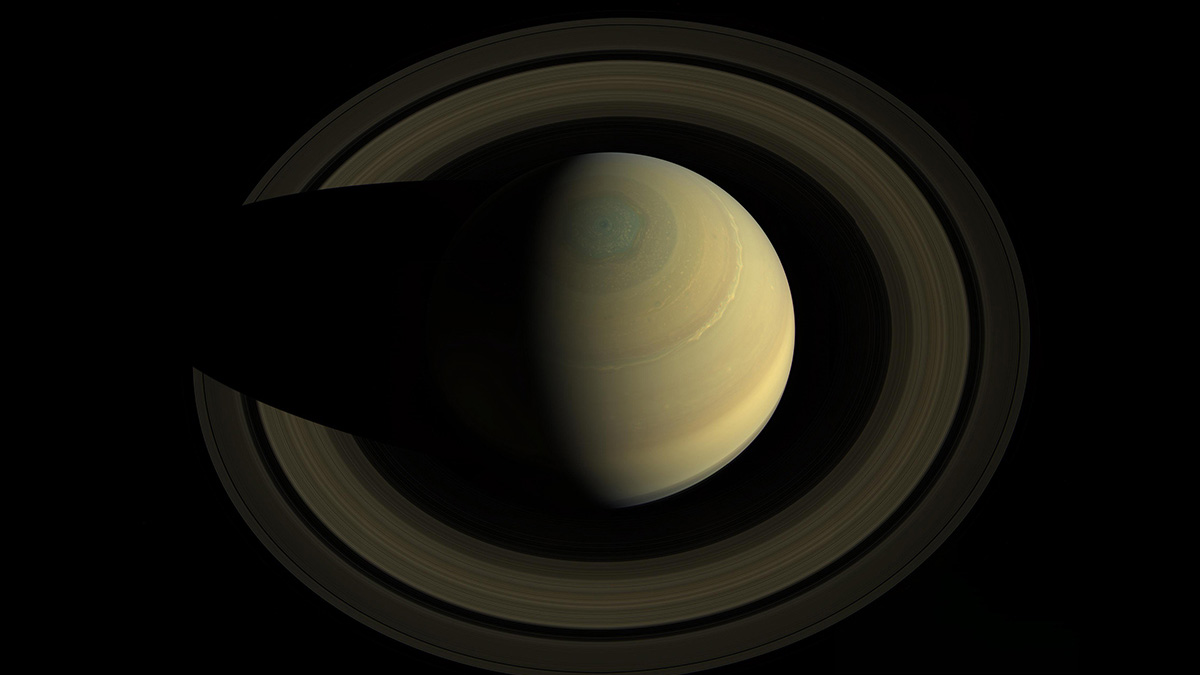

Undoubtedly, of the wonders of the solar system, Saturn's angelic rings stand out as a fan-favorite. And in 1997, with its eye on the prize, the Cassini spacecraft embarked on a seven year voyage to Saturn with the mission of conducting the most rigorous survey ever of the planet, its moons and, of course, those spectacular rings.

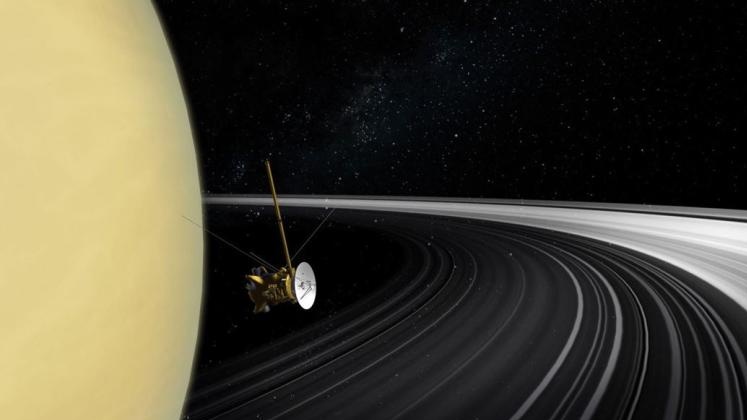

Before the spacecraft plunged into Saturn's atmosphere in 2017, Cassini repeatedly flew between the planet and its rings while collecting an abundance of data. Now, using that data, captured with the Langmuir Probe onboard the craft, planetary scientists have measured the optical depth of Saturn's rings — albeit in an unconventional way. It has to do with solar eclipses the spacecraft "saw" while on its journey. Here's what that means.

First, it's important to know that the optical depth of a substance is related to how far light can travel through that substance before getting absorbed or scattered. Optical depth is also connected to how transparent an object is.

Related: Saturn's rings shine in James Webb Space Telescope photo of the gas giant

Cassini, eclipsed

Ph.D. student George Xystouris from the University of Lancaster realized there could well be a relationship between "solar eclipse" events witnessed by the spacecraft, referring to when the probe moved into shadows behind Saturn or its rings, and the rings' optical depth. If true, the transparency of Saturn's rings would be directly present in Cassini data.

"We use all available solar eclipses as seen from Cassini by either Saturn or its rings," the study authors write, "periods where Cassini goes into the shadow of Saturn or its rings."

It had already been known that the Langmuir Probe onboard Cassini was an instrument designed to measure cold plasma — a mixture of low energy ions and electrons — in the magnetosphere of Saturn. But because the probe itself was metallic in composition, when Cassini was in the sunlight, the rays provided enough energy for the probe's material to release some electrons in a process known as the photoelectric effect. Therefore, not only was the probe detecting electrons from the magnetosphere, it was also detecting electrons created by the sun striking its metallic body.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The probe thus recorded significant changes in the intensity of electron data as it moved in and out of the shadow of the planet and its rings. And Xystouris realized these changes would be connected to the amount of sunlight moving through each of Saturn's rings — which would allow him to sort of reverse calculate the rings' optical depth.

"Eventually, using the properties of the material that the Langmuir Probe was made of, and how bright the sun was in Saturn’s neighborhood, we managed to calculate the change in the photoelectrons number for each ring, and calculate Saturn’s rings optical depth," Xystouris said in a statement.

"We used an instrument that is mainly used for plasma measurements to measure a planetary feature, which is a unique use of the Langmuir Probe, and our results agreed with studies that used high-resolution imagers to measure the transparency of the rings," he added.

While the main rings of Saturn extend out to 140,000 kilometers (roughly 87,000 miles) from the planet, the team found, the maximum thickness of the rings only reaches one kilometer. The iconic rings are also set to disappear from view from Earth by 2025 as they tilt back towards us in the next phase of Saturn's 29-year orbit. But don't worry, they won't be absent from keen stargazers telescopes for too long. They should only be gone for a few months.

The research was published in September in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Conor Feehly is a New Zealand-based science writer. He has earned a master's in science communication from the University of Otago, Dunedin. His writing has appeared in Cosmos Magazine, Discover Magazine and ScienceAlert. His writing largely covers topics relating to neuroscience and psychology, although he also enjoys writing about a number of scientific subjects ranging from astrophysics to archaeology.