Saturn's planet-wide storms driven by seasonal heating, Cassini probe reveals

"We believe our discovery of this seasonal energy imbalance necessitates a reevaluation of those models and theories."

Like a lightbulb switching between high- and low-power modes, Saturn pumps into space varying amounts of heat based on its seasons, a fresh analysis of data from NASA's Cassini spacecraft reveals.

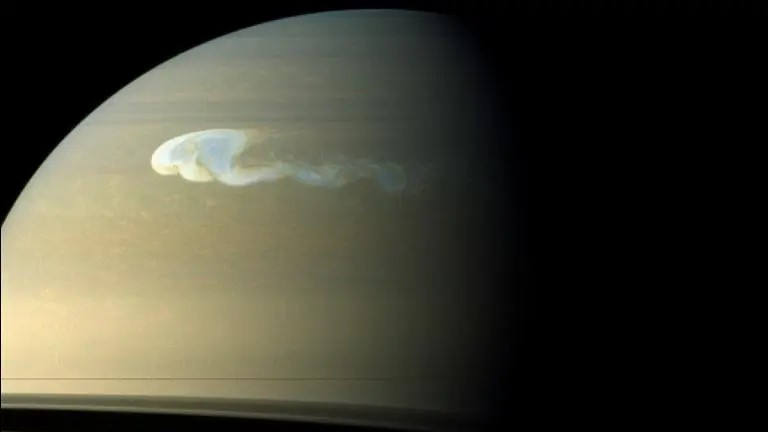

A noticeable effect of this flux is turbulence in Saturn's atmosphere, which whips up storms across its north and south hemispheres strong enough to wrap around the planet, scientists report in a paper published Tuesday (June 18) in the journal Nature Communications.

Such seasonal changes in radiated heat from Saturn and other gas giants are yet to be included in models describing their climates and evolutions, which assume the planets emit heat evenly in all directions and at a steady rate, Liming Li, a physics professor at the University of Houston, who a decade ago found Saturn does not emit energy evenly and is a co-author of the new study, previously told Space.com.

"We believe our discovery of this seasonal energy imbalance necessitates a reevaluation of those models and theories," Xinyue Wang of the University of Houston in Texas, who led the new study, said in a recent statement.

Astronomers have long known that Saturn returns to space double the energy it soaks up from the sun. The extra energy comes from deep within Saturn, where heat left over from its birth pushes temperatures to about 15,000 degrees Fahrenheit (8,300 degrees Celsiuss) — hotter than the surface of the sun. Much of this internal heat is a byproduct of the planet slowly compressing due to its gravity, and some may arise from friction sparked by lots of helium sinking toward the planet's core.

When NASA's Cassini spacecraft arrived at Saturn in 2004, the gas giant was in the middle of a southern summer with its south pole pointed toward the sun, while its northern hemisphere was blanketed in the darkness of winter. Equal amounts of sunlight warmed both halves of the planet in 2009, when the equinox arrived. Cassini witnessed three seasons play out in Saturn's northern hemisphere before the probe's intentional death plunge into the gas giant's atmosphere in September 2017: spring, summer and winter, each of which lasts about seven Earth years.

While previous research led by Li had shown that the heat radiated by Saturn matched its seasons, the new study finds those periodic changes to also be due to changing amounts of sunlight absorbed as the gas giant swings widely between the closest and farthest points in its egg-shaped, 30-year-long orbit around the sun.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Not only does this give us new insight into the formation and evolution of planets, but it also changes the way we should think about planetary and atmospheric science," Li said in the statement.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social