Scientists unlock the 'Cosmos' on the Antikythera Mechanism, the world's first computer

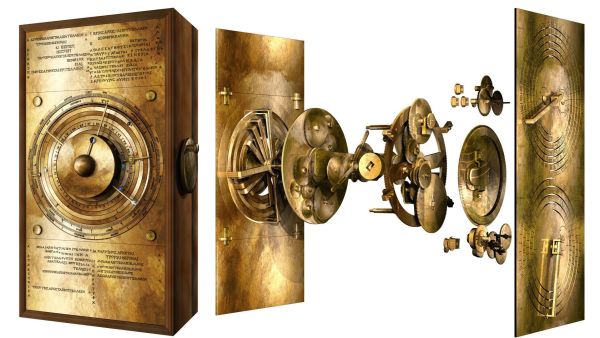

Scientists may have finally made a complete digital model for the Cosmos panel of a 2,000-year-old mechanical device called the Antikythera mechanism that's believed to be the world's first computer.

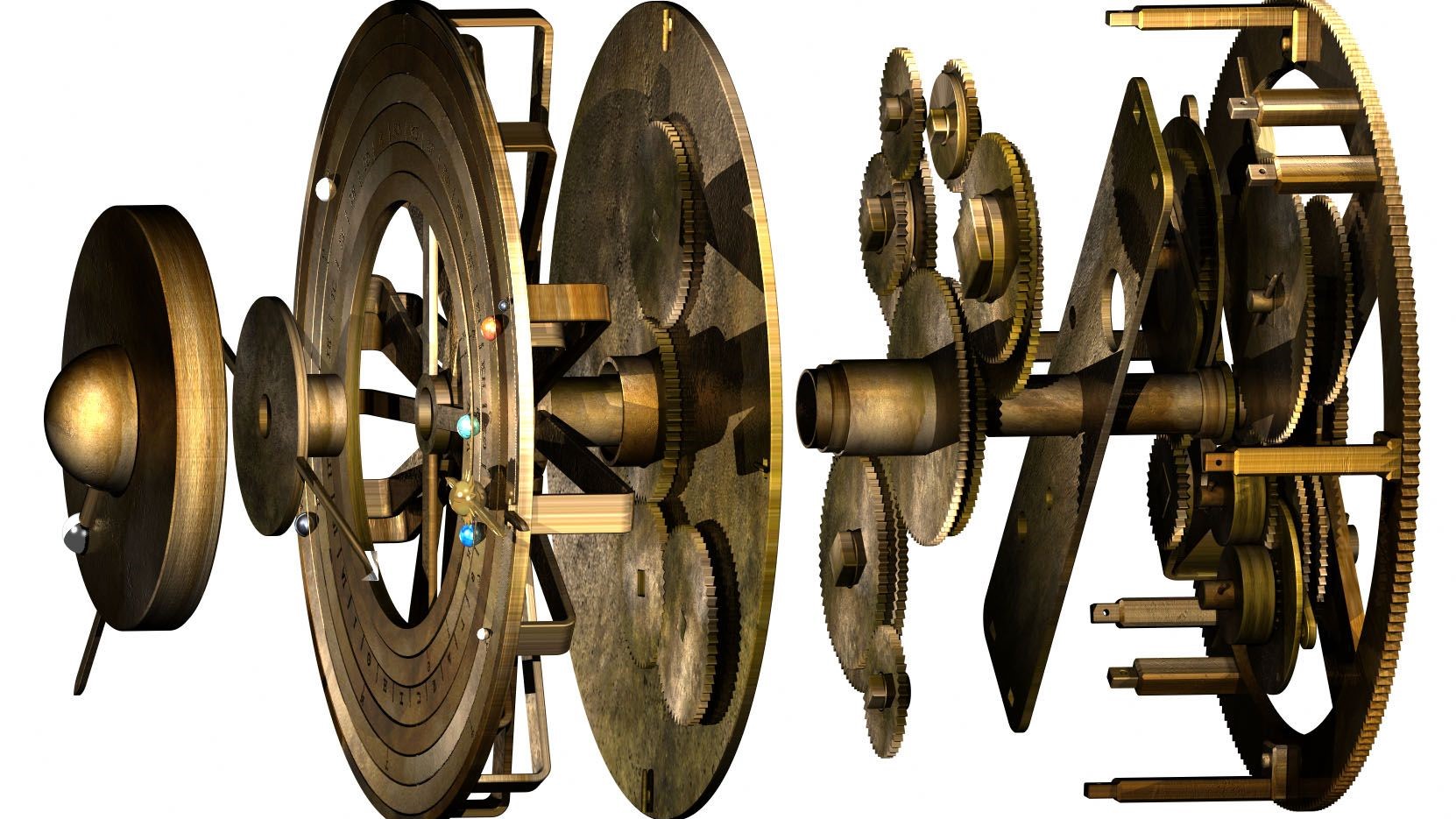

First discovered in a Roman-era shipwreck by Greek sponge divers in 1900, the fragments of a shoebox-size contraption, once filled with gears and used to predict the movements of heavenly bodies, has both baffled and amazed generations of researchers ever since.

The discovered fragments made up just one-third of a larger device: a highly-sophisticated hand-powered gearbox capable of accurately predicting the motions of the five planets known to the ancient Greeks, as well as the sun, the phases of the moon and the solar and lunar eclipses — displaying them all relative to the timings of ancient events such as the Olympic Games.

Related: Photos: Ancient Greek shipwreck yields Antikythera mechanism

Yet despite years of painstaking research and debate, scientists were never able to fully replicate the mechanism that drove the astonishing device, or the calculations used in its design, from the battered and corroded brass fragments discovered in the wreck.

But now researchers at University College London say they have fully recreated the design of the device, from the ancient calculations used to create it, and are now putting together their own contraption to see if their design works.

"Our work reveals the Antikythera Mechanism as a beautiful conception, translated by superb engineering into a device of genius," the researchers wrote on March 12 in the open-access journal Scientific Reports. "It challenges all our preconceptions about the technological capabilities of the ancient Greeks."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Why recreate Antikythera?

The researchers wanted to recreate the device because of all the mystery surrounding it, as a way to possibly get to the bottom of so many questions. In addition, nobody had ever created a model of the so-called Cosmos that reconciled with all of the physical evidence.

"The distance between this device's complexity and others made at the same time is infinite," co-author Adam Wojcik, a materials scientist at UCL, told Live Science. "Frankly, there is nothing like it that has ever been found. It's out of this world."

The intricate gears that made up the device's mechanism are of a scale you could expect to find in a grandfather clock, but the only other gears discovered from around the same period are the much larger ones that went into things like ballistas, or large crossbows, and catapults.

This sophistication brings up a lot of questions about the manufacturing process that could have made such a uniquely intricate contraption, as well as why it was discovered as the only known device of its kind on an ancient sunken ship off the island of Antikythera.

Related: The 20 most mysterious shipwrecks ever

"What is it doing on that ship? We only found one-third; where are the other two [thirds]? Have they corroded away? Did it ever work?" Wojcik said. "These are questions that we can only really answer through experimental archaeology. It's like answering how they built Stonehenge, let's get 200 people with some rope and a big stone and try to pull it across Salisbury Plain. That's a bit like what we're trying to do here."

Making the first computer

To create the model, the researchers drew on all of the past research on the device, including that of Michael Wright, a former curator at the Science Museum in London, who had previously constructed a working replica. Using inscriptions found on the mechanism and a mathematical model of how the planets moved that was first devised by the ancient Greek philosopher Parmenides, they were able to create a computer model for a mechanism of overlapping gears that fit inside a just barely 1-inch-deep (2.5 centimeters) compartment.

Related: Ancient Greek Antikythera Mechanism came with a user guide

Their model recreates each gear and rotating dial to show how the planets, the sun and the moon move across the Zodiac (the ancient map of the stars) on the front face and the phases of the moon and eclipses on the back. It replicates the now-outdated ancient Greek assumption that all of the heavens revolved around the Earth.

Now that the computer model has been made, the researchers want to make physical versions, first using modern techniques so they can check that the device works, and then employing the techniques that could have been used by the ancient Greeks.

"There's no evidence that the ancient Greeks were able to build something like this. It really is a mystery," said Wojcik. "The only way to test if they could is to try to build it the ancient Greek way."

"And there's also a lot of debate about who it was for and who built it. A lot of people say it was Archimedes," Wojcik said. "He lived around the same time it was constructed, and no one else had the same level of engineering ability that he did. It was also a Roman shipwreck." Archimedes was killed by Romans during the Siege of Syracuse, after the weapons he invented failed to prevent them from capturing the city.

Mysteries also remain as to whether the ancient Greeks used similar techniques to make other, yet-to-be-discovered, devices or whether copies of the Antikythera mechanism are waiting to be found.

"It's a bit like having a TARDIS appear in the Stone Age," said Wojcik, referring to Doctor Who's time-traveling spacecraft.

Originally published on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like weird animals and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.