US Navy's 'Aquanauts' Tested the Boundaries of Deep Diving. It Ended in Tragedy.

In the 1960s, NASA's first astronauts tested the limits of human endurance far above the planet. Meanwhile, teams of intrepid divers explored similar boundaries in an equally inhospitable environment here on Earth: the dark, numbingly cold and high-pressure depths of the ocean.

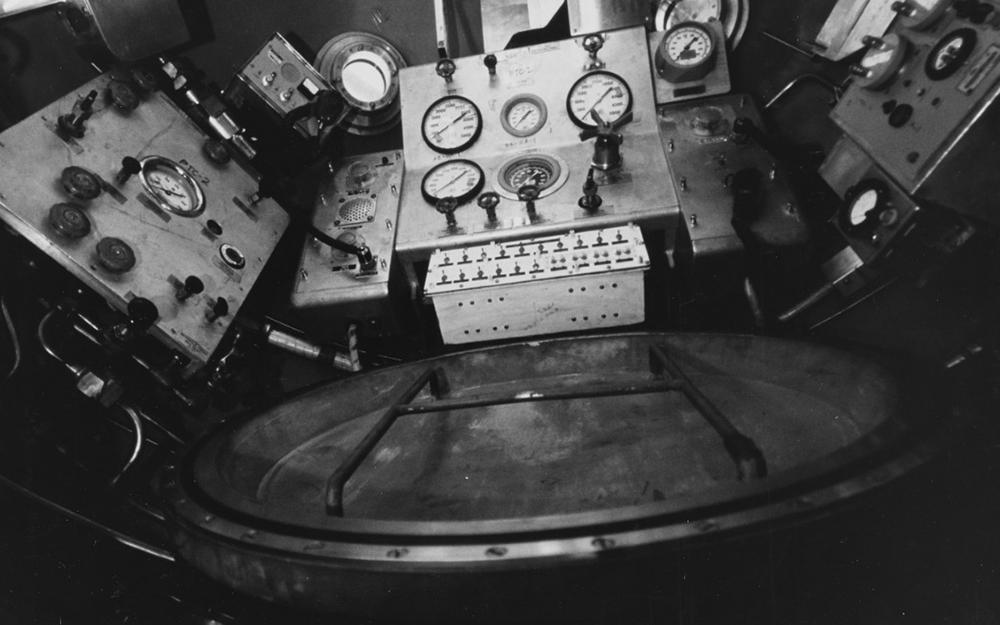

Dubbed "Sealab," the grueling program was launched by the U.S. Navy during the Cold War. Participants called "aquanauts" trained to survive underwater in a pressurized environment for days at a time, at depths that created enormous physical challenges. Over three stages, the Sealab environments descended to greater and greater depths. But with the death of a diver in 1969, officials decided that the risks were too great, and they terminated the program.

The long-forgotten story of the aquanauts surfaces in a new documentary called "Sealab," airing Feb. 12 on PBS at 9 p.m. ET (check local times). [Gallery: Declassified US Spy Satellite Photos & Designs]((VideoProviderTag|jwplayer|gG7H0X9I|100%|100%))

From the 1950s into the 1960s, the U.S. and the Soviet Union were engaged in a heated race into space. But they were also eyeing each other's progress in the development of deep-sea technology for submarine warfare. To that end, the U.S. Navy established a program to test just how deep into the ocean humans could go, Stephen Ives, director and producer of "Sealab," told Live Science.

"Ironically, the ocean is far more accessible than the stratosphere, and yet, it's remained more of a mystery than space," Ives said.

The deep ocean exerts crushing pressure on the human body, compressing oxygen in the lungs and tissues. The deeper a diver descends, the more time is required for the body to return safely to normal surface pressure. Rising from the depths too quickly releases nitrogen bubbles in body tissues, causing the bends — excruciatingly painful cramps and paralysis, which can be lethal.

Deeper and deeper

For the project's first undersea laboratory — Sealab I, in 1964 — the Navy introduced a new technique called saturation diving. The aquanauts inhabited a special environment that saturated their bloodstream with helium and other gases that were at the same pressure as the surrounding water, enabling the explorers to spend longer periods in the deep sea without risk of decompression sickness, according to a report published in June 1965 by the Office of Naval Research (ONR).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For 11 days, four aquanauts lived and worked in a seafloor laboratory near Bermuda at at depth of 193 feet (59 meters) below the surface, breathing a mixture of helium, oxygen and nitrogen, the ONR reported.

In 1965, Sealab II touched down on the seafloor at a depth of 203 feet (62 m), near La Jolla, California. The successful 30-day mission earned aquanaut Scott Carpenter a congratulatory phone call from President Lyndon B. Johnson on Sept. 26, 1965. Carpenter spoke to the president while still decompressing from the experience, and his voice was unusually high-pitched from the helium-rich environment, according to the National Archives.

In a recording of the call, Johnson appeared unfazed by Carpenter's cartoonish voice, enthusiastically thanking him and saying, "I want you to know that the nation's very proud of you."

An enduring legacy

But tragedy struck the project in February 1969 after Sealab III was lowered to the sea bottom off the coast of San Clemente, California, to a depth of 600 feet (183 m). When divers descended to fix a helium leak in the still-unoccupied habitat, aquanaut Berry Cannon died of carbon dioxide asphyxiation. His death put an end to Sealab and all of the U.S. Navy's saturation-diving experiments, according to the U. S. Naval Undersea Museum.

Though Sealab ended nearly half a century ago, it had a lasting impact on marine research and deep-sea exploration, Ives said. One current endeavor that owes much to the program is the Aquarius Underwater Laboratory — the world's only fully equipped undersea laboratory — formerly owned by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and now owned and operated by Florida International University.

Located near Key Largo in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, Aquarius rests on the seafloor about 60 feet (18 m) below the surface, allowing researchers to live and work underwater for missions that typically last 10 days, according to NOAA.

But another important part of Sealab's legacy was sparking a long-standing scientific commitment to study the deepest parts of Earth's oceansand to investigate how they affect climate and ecosystems worldwide, Ives said.

"It helped lead the way to a new understanding of how important oceans are to our world — they're the planet's life-support system," Ives said. "And I think Sealab helped us to see that."

Editor's note: This article was updated to reflect that NOAA no longer owns the Aquarius underwater laboratory.

Originally published on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.