What's that smell? Astronomers discover a stinky new clue in the search for alien life

It's not that sulfur is a great indication that a planet is inhabited. Instead, it's the opposite.

Astronomers have discovered that sulfur may be a key to helping us narrow down our search for life on other planets. It's not that sulfur is a great indication that a planet is inhabited. Instead, it's the opposite: Significant amounts of sulfur dioxide in a planet's atmosphere is a good sign that the world is uninhabitable and we can safely cross it off the list of candidates.

One of the holy grails of modern astronomy is finding life on an alien planet. But that is an extremely daunting task. The James Webb Space Telescope is unlikely to be able to identify biosignatures — the atmospheric gases produced by life — in any nearby worlds. And the upcoming Habitable Worlds Observatory will be able to scan only a few dozen potentially habitable exoplanets.

One of the big hurdles is that biosignature spectra are usually very weak. So one way to narrow down the list of potential candidates is to focus on the ability of a planet to host life, mainly in the form of water vapor in its atmosphere. If a planet has a lot of water vapor, it might have a good chance of hosting life as well.

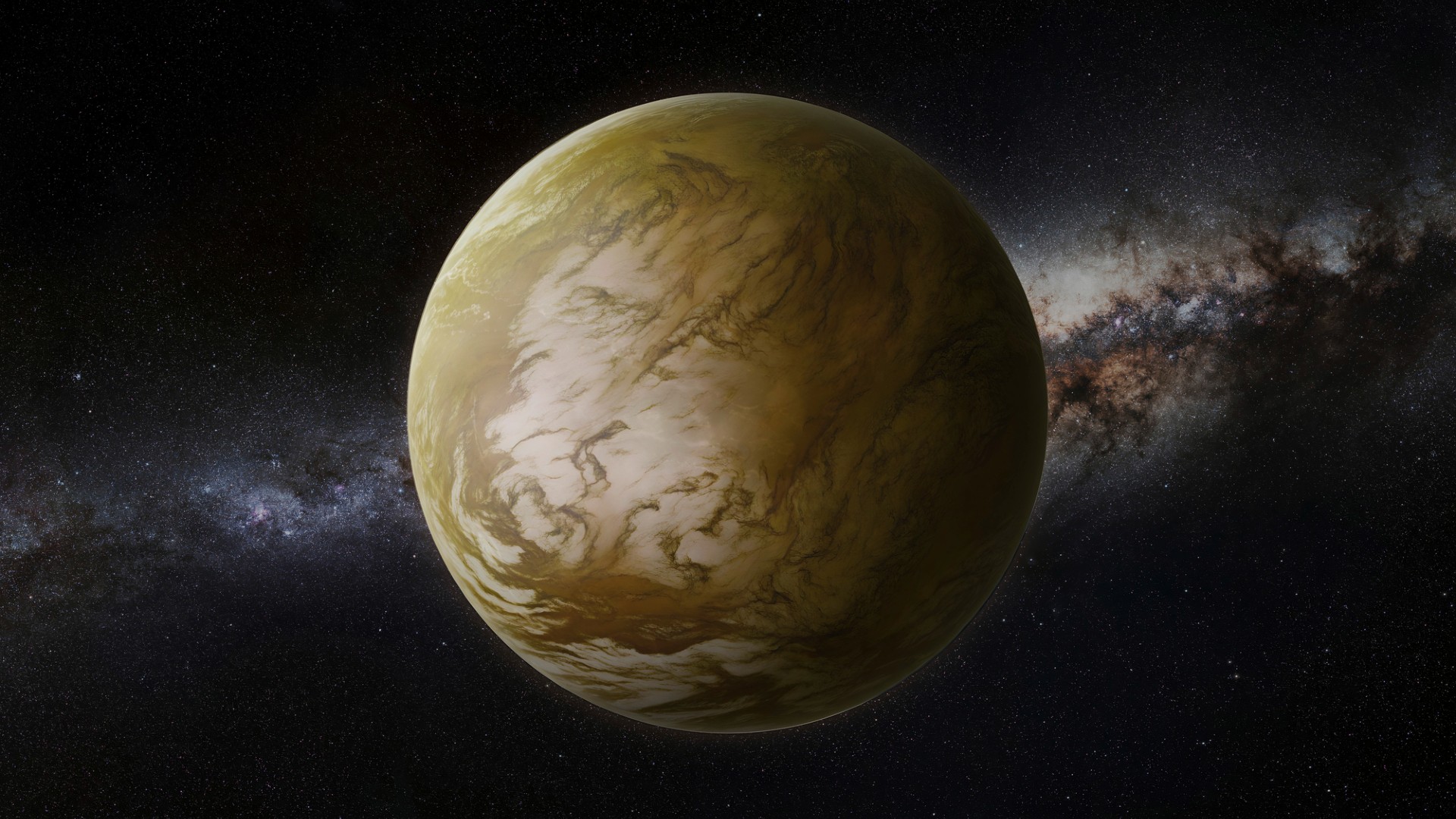

This requirement is the basis of the habitable zone, the region around a star where the radiation onto a planet isn't too little that all the water freezes out and isn't too much that the water boils away. In our solar system, Venus is near the inner edge of the habitable zone, and its surface reaches temperatures of over 800 degrees Fahrenheit (427 degrees Celsius) underneath a thick, choking atmosphere. On the opposite end, Mars is essentially frozen out, with all of its water locked up in polar ice caps and under the surface.

But even a search for water has difficulties. For example, from great distances, it's very difficult to tell Earth (inhabited) apart from Venus (uninhabited and outright hostile to life). Their atmospheric spectra are just too similar when you're trying to hunt for water vapor.

In a recent preprint paper, astronomers note that they've found a different signature gas that might be a useful tool for separating uninhabitable worlds from potentially habitable ones: sulfur dioxide.

Warm, wet worlds like Earth have very little sulfur dioxide in their atmospheres. That's because rain can pick up atmospheric sulfur dioxide and wash it down into the oceans or into the soil, essentially cleansing it out of the atmosphere.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And, ironically, planets like Venus also have very little sulfur dioxide. In that planet's case, high amounts of ultraviolet radiation from the sun catalyze reactions that convert sulfur dioxide to hydrogen sulfide in the upper atmosphere. There's still a lot of sulfur dioxide, but it tends to slink down into the lower atmosphere, where it can't be detected.

Thankfully, there's another option: planets around red dwarf stars. Red dwarfs emit very little ultraviolet radiation. So if a dry, uninhabitable planet were to form around a star like that, a lot of sulfur dioxide would persist in its upper atmosphere.

Astronomers are especially interested in the planetary systems of red dwarfs. One reason is that red dwarfs are the most common kind of star in the galaxy. The other is that many nearby systems — like our nearest neighbor, Proxima Centauri, as well as TRAPPIST-1 — are red dwarfs known to host planets. This makes them very appealing targets for upcoming searches for life.

The new technique based on sulfur dioxide can't tell us which planets might host life, but they do tell us which planets probably don't. If we see a rocky planet orbiting a red dwarf and detect an abundance of sulfur dioxide in its atmosphere, it is likely a lot like Venus — a dry, hot world with a thick atmosphere and little to no water. Not a good candidate for life.

But if we fail to see any significant sulfur dioxide, that world is likely a good candidate for a follow-up observation to search for signs of water vapor and, if we're lucky, life.

It's going to take an enormous amount of detective work and dogged determination to find life on another planet. So any clue we can get, even one based on sulfur dioxide to narrow down our list, is welcome.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Paul M. Sutter is an astrophysicist at SUNY Stony Brook and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy, His research focuses on many diverse topics, from the emptiest regions of the universe to the earliest moments of the Big Bang to the hunt for the first stars. As an "Agent to the Stars," Paul has passionately engaged the public in science outreach for several years. He is the host of the popular "Ask a Spaceman!" podcast, author of "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space" and he frequently appears on TV — including on The Weather Channel, for which he serves as Official Space Specialist.